Opulence and openness

A cultural history of opera at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

An exhibition on opera? That sounds like something akin to a colourful collection of mounted butterflies. After all, what should you expect when perhaps the most abundant art form migrates to display cabinets? At best, faded costumes, yellowed musical manuscripts, models of historical stage sets, a couple of audio samples and teachings on the history of music.

The complete opposite of such a banal line-up is provided by the superbly staged exhibition “Opera: Passion, Power and Politics” in the new, discreetly elegant Sainsbury Gallery of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. A staged exhibition? This is a fitting description as the creators of this exhibition have used exactly the same ingredients that you find in a good opera. The best libretto and the best soloists are nothing without effective staging - and gripping music, of course.

Now, this is normally a problem in exhibitions. Audio terminals, greasy headsets, audio guides – no, thanks. For “Opera” you are given clean headsets and a receiver. When you switch it on, as you move through the exhibition you automatically hear opera extracts that go with the exhibits. These extracts have been carefully selected and are commented on spiritedly by Antonio Pappano, the Music Director of The Royal Opera at Covent Garden in London.

Views of the exhibition. Photos: Victoria and Albert Museum

At the same time, the tour is a well-structured journey through some four hundred years of opera history. This might have been exhausting, but it works because the selection is limited to seven exemplary opera premières. This also makes the exhibition more accessible to visitors who are less versed in music history. Thanks to the clear framework and the brief post-it-style introductions, the wealth of outstanding exhibits, which include musical scores on show for the first time ever as well as revered objects like a piano played by Mozart, remains manageable.

Using the seven examples, what the exhibition ultimately unfurls is nothing short of a cultural history of Europe as reflected by one of its most refined and complex forms of art. The opera – not unlike the novel – appears to be an extremely pliable genre. The samples of music reinforce the idea that opera translates the respective social climate into musical moods and atmospheres. This is probably illustrated best by Strauss’ Salome as a symbolic figure of an edgy dawning of the modern age.

But we are almost at the end of the exhibition there. It starts with Claudio Monteverdi’s “L’incoronazione di Poppea”. This premièred in Venice in 1642. This is where the history of modern opera began; it was crafted here as a drama of passions which could trigger social and political upheaval in the soul – and as great entertainment. At that time, the Republic of Venice had passed its peak as a naval power. So, it was all the more important that it now, in contrast to Papal Rome, presented itself as a sparkling cultural centre. The Venetian Carnival provided the perfect setting for a Late Roman scandal, such as that of Nero’s power-hungry lover Poppea. The history of modern opera as a commercial multimedia show could only begin here.

View of Venice, print, Frederick de Wit, Netherlands. Museum no. E.1539-1900. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

From Venice we move on to London during the Early Enlightenment, already back then the largest city in Europe. Here George Frideric Handel achieved success with “Rinaldo”. It is fascinating how every single exhibit contributes a significant facet to a vivid portrait of this era. The early beginnings of a culture of public debate in cafés are illustrated here with engravings by Hogarth and tea sets from the period. The city was thriving as a centre of colonial trade with the East India Company established in 1708. We discover that the successful composer Handel held shares in the slave trade. On the other hand, exquisite goldsmith works point to London as a place of refuge for the religiously persecuted Huguenots, among others. Still today the reconstruction of a mechanical stage setting with waves, boat and mermaids has the power to thrill the public. Tricks and gags of all kinds – opera has always been a field of experimentation for these, too.

Then comes Mozart’s Vienna, awash with the spirit of the Enlightenment, which is where he composed his “Figaro”. Soon afterwards, opera became truly supportive of the state in Milan: Verdi was the composer of the “Risorgimento”, the national awakening of Italy, to which he contributed the soundtrack with the famous prisoners’ chorus from “Nabucco”. He absolutely hypnotised the country; his death in 1905 was a national event. Another part of this heritage are the 150 opera houses established at that time, though these days they are more of a burden for the cities concerned. They are presented in a stunning photographic parade.

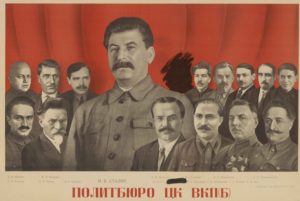

Paris in the late 19th century was not only quite literally being shaken by major political and urban transformations. Richard Wagner’s hotly discussed “Tannhäuser” was also causing a stir. In contrast, the last two stations place the spotlight on artistic freedom, which is a highly topical issue again today. In Dresden, which was a hotbed of the avant-garde in 1905, Richard Strauss’ Salome was not censored – unlike in Vienna. But when Dmitri Shostakovich’s “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” premièred in St Petersburg/Leningrad in 1934, a new wind was blowing. Comrade Stalin had just realised that, alongside film, opera was also ideal for propaganda and to manipulate the masses. But, unfortunately, not Shostakovich’s. Despite its public success, it was condemned as a “muddle instead of music” in 1936 after Stalin made a visit to the opera. The composer became a puppet of those in power.

Politbureau ZKVKP (B) (Central Committee of the All Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik), poster, Gustav Klutsis, 1935, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Museum no. E.1267-1989. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Of course, opera regularly faces criticism: it is seen as too elitist or too expensive. Yet, it carries on quite happily, that’s for sure! This is demonstrated by a spacious video lounge in the heart of the exhibition, which invites you to stop for a while. The two qualities to which it owes its now global success are reaffirmed here: opulence and openness, even for the seemingly impossible like Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Helicopter String Quartet.

“Opera: Passion, Power and Politics” – the title promises much, but not too much. The museum recommends that visitors allow seventy minutes. You could easily double that time.

Opera: Passion, Power and Politics

until 25 February 2018

Victoria and Albert Museum London

E-ticket reservations recommended