The life of a woman in service for the upper classes

Without servants, most of them female, the extravagant lifestyle of a well-to-do family in centuries past would have been unthinkable. A glimpse behind the brilliantly polished façade of a grand household, with a focus on Jegenstorf Castle near Bern.

Until well into the 20th century, domestic servants, predominantly women, did the work that piled up in the large households of wealthy families of the nobility, aristocracy and upper middle classes. Especially in stately homes, a large team of staff for house and garden was necessary to enable aristocratic families to live and be seen to live in a manner befitting their social status.

In the hierarchy of servants, the maid was at the very bottom. Nevertheless, around the year 1900 this job continued to be the most common occupation for women of the lowest social classes who did not live or work on a farm. These maidservants came mainly from the countryside, where there were few employment opportunities for women. Many had no other option for bridging the gap between leaving home and possibly getting married. Education was not available to them. Consequently, many maids started their careers in service at the age of just 14 or 15. In contrast to factories, which from the second half of the 19th century offered women an alternative to life as a servant, those who ‘entered service’ at least learned important skills that would serve them later on as housewives, according to the widely held view at the time.

Bernese maid in traditional costume. Lithograph by François-Séraphin Delpech, circa 1825. Photo: Swiss National Museum

Always at your service

The everyday life of a maid consisted of physically demanding work. She was the first to get up, lit the wood-burning stoves, fetched water for the kitchen, served the meals and cleared away afterwards, and worked continuously to keep the place clean and tidy. In between, she had to run errands and do the shopping. These were coveted tasks, as they allowed her to get out of the house for short periods. They provided the only opportunity to be a part of the life outside her workplace and have a quick natter on the village square.

The maidservant did not have regular working hours. Her leisure time was extremely limited; she had a few hours off every other week, on a Sunday. This time was usually used to visit her own family or to go to church. The latter activity was also one of the rare opportunities to mix with people outside the household. It was virtually impossible to maintain private contacts; she was not allowed to receive any visitors. Her own needs were as good as non-existent; her life revolved around her service.

The young women were required to be ‘always at the service’ of their employers, and to attend to the wishes and requests of the noble family around the clock – including at night if necessary. Evenings were usually late, especially if there were guests in the house, which was often the case. Before going to bed herself, there was usually time only to mend her own clothes, which were expected to be immaculate and clean at all times, or for a chat with a colleague, with whom in many cases she shared a room. These were usually small, unheated rooms under the eaves, which were very sparsely furnished. Even though board and lodging made up the majority of a maid’s pay, the food was often just as miserable as the accommodation.

Servants’ bell board from Jegenstorf Castle, late 19th century. The bell board showed the servants in which room a member of the family needed their assistance. Photo: Stiftung Schloss Jegenstorf

Maids received very little thanks for their hard work. On the contrary: many were regarded with contempt, and were treated accordingly. Not infrequently, the young women had to deal with harassment by the man of the house and his sons – often with the knowledge of the lady of the house, who turned a blind eye. If a maid became pregnant, she was accused of immorality and vice. She was then dismissed immediately, to avoid a family and social scandal.

Chambermaid at the Hotel Beaurivage, circa 1865. Photo: Swiss National Museum

Maid at work, circa 1900. Photo: Swiss National Museum

Portrait of an unknown servant. Photo: Swiss National Museum

The dependent relationship between the maid and the family she worked for culminated in the mandatory service record book, the ‘Dienstbüchlein’, which served as a means of inspection and a bargaining tool. In this book, the lady of the house recorded the duration of the maid’s employment, her duties, and wrote a brief letter of reference. Only a maid with a complete and unblemished Dienstbüchlein would be able to find another position. From one day to the next, the maid could be dismissed and shown the door. No reason was needed – or would be fabricated, if necessary.

Washerwoman at work. Sketch by Sigmund Freudenberger, circa 1770. Photo: Swiss National Museum

The maid’s duties did not include doing the laundry, one of the most laborious tasks in the household until the invention of the washing machine. The job of the hired washerwoman was one of the most wretched. Not members of the permanent staff, washerwomen were day-labourers who served in various households as required and on a short-term basis. As a result, they had an inside glimpse into different households and on occasion were also privy to private, even intimate details. Exchanging news and gossip while working was the order of the day, to provide some relief from the drudgery. The fact that the term ‘Waschweibergetratsche’, or in English to gossip like an old washerwoman, is still in regular use harks back to this activity.

Nursing someone else’s child

In upper class households, the mother and lady of the house had little involvement in looking after her own children. Their care and education was often left to others. Nannies looked after the babies, and teachers and governesses took care of the older children. Until the 20th century, so-called ‘Lohnammen’ (hired wet nurses) were an established part of the well-to-do household in Europe. In addition to breast-feeding, their duties included taking care of the infant’s personal hygiene.

Wet nurses, like the other staff to whom the children’s care was entrusted, had a comparatively high standing among the servants. Since it was important that the wet nurse was in good health and produced plenty of nourishing milk, she herself was fed well. The wet nurse often lived on the same floor as the family, sometimes even alone with the child in a separate bedroom. She was therefore better accommodated than other domestic staff. There was one main reason for this: it allowed the wet nurse to tend to the child around the clock. After all, the lady of the house wished to recover from the exertions of childbirth and did not wish to be woken repeatedly in the middle of the night.

It was usually married mothers, often farmers’ wives, who hired themselves out as wet nurses after the birth of their own child. Only if no other option were available would a single mother who had recently given birth be hired. Having children out of wedlock was considered a sin, and unmarried mothers were therefore ostracised. Because of the prevailing notion that negative character traits and poor moral conduct could be passed on via breast milk, married women from ‘orderly circumstances’ were preferred. The more affluent the family, the more selective they could be in their search for the right wet nurse.

Over time, the hiring of wet nurses was increasingly criticised. On the one hand, the child became alienated from its own mother, while at the same time forming a close bond with the wet nurse who might disappear from its life from one day to the next. The wet nurse, for her part, was forced to neglect her own offspring during her absence, leaving them to be given basic care by relatives. In addition, there was a growing awareness in the 19th century that illnesses, especially infections, were passed on via breast milk.

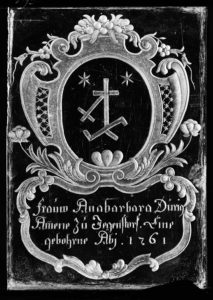

Thanks to a small ground glass plate with the inscription ‘Miss Anna Barbara Dürig, wet nurse at Jegenstorf 1761’ under the Dürig (of Jegenstorf) coat of arms, we have some details of a wet nurse who probably served in Jegenstorf Castle. The plate is currently on display at Jegenstorf Castle in the special exhibition ‘Our Women’, see box below. It is quite possible that she was given the plate as a token of thanks by the family for whom she worked, at the end of her service. Other than at the castle, then in the possession of the von Stürler family, it is unlikely she would have been employed anywhere else. Dürig is an old Jegenstorf farming family that is still around today.

The future King Ludwig XIV with his wet nurse. Photo: Wikimedia

Glass plate with inscription: ‘Miss Anna Barbara Dürig, wet nurse of Jegenstorf 1761’. Property and photo: Bern Historical Museum, Berne

Lina, the castle cook

Cooking was one of the more prestigious jobs in a high-ranking household; the cook, who could be either male or female, was therefore respected among the domestic staff. He or she didn’t have to do any dirty, unpleasant work, and the workload was usually lightened by other subordinate servants such as a kitchen maid. If they did a good job, they were held in high esteem by the family. More often than not, in contrast to the other servants, cooks had undergone training to learn the art of cooking to a high standard.

We know one of the cooks from Jegenstorf Castle by name: Karolina-Bertha Junker-Weber (1895–1940), known to everyone as Lina. Born in Grossbottwar, Baden-Württemberg, in 1895, after leaving school she completed an apprenticeship as a cook and first served in Berlin during the First World War, before moving to Switzerland and being hired as a cook at Jegenstorf Castle. Her employers were the last private owners of the Castle, Arthur and Margarethe von Stürler.

Lina was considered an efficient and excellent cook. According to records, it was only the slaughtering of chickens that she was not too keen on. Ruedi Junker, the son of the neighbouring farmer, helped her with that task. In return, Lina would bake him a cake. In 1921 the couple married, and went on to have four children. Although Lina now had to take care of a household and family of her own, and probably help out on the farm too, she remained loyal to Jegenstorf Castle – albeit no longer as a cook. Together with her only daughter, Ruth, in the cooler months she got up early in the morning to light the wood-burners in the castle, of which there were more than a dozen.

The cook, Karolina-Bertha (Lina) Junker, circa 1930. Photo from a private collection

Among Lina’s belongings was found a little hand-written cookbook containing recipes created during her time in service at the castle. As yet unedited, the melange of German, French and Swiss cuisine is a real gem of the art of upper class cookery. It is currently on display in the castle and a copy is available for browsing through.

The Verein Schloss Jegenstorf (Jegenstorf Castle Association), which bought the castle at auction in 1936 with the aim of making the property a public museum, still exists. The Foundation, and current owner of Jegenstorf Castle, emerged out of the Association in 1955. Of course, we no longer have service staff in the original sense. But the couple who look after the castle live in the rooms – adapted to today’s living and modern requirements – in which the servants used to be housed. The two of them keep the castle and its park looking their splendid best at all times – for you and other visitors.

Jegenstorf castle in 1890: Members of the von Stürler family in the park in front of the castle, at far left probably a teacher or a lady’s companion, in the window a maid with the sick lady of the house. Photo: Stiftung Schloss Jegenstorf