For peace in a time of war

The outbreak of World War I came as a surprise to the peace movement, although many pacifists had long warned of such a danger. As a neutral state and surrounded by warring nations, Switzerland played a central role in peace discussions.

The outbreak of war in August 1914 hit the peace movement in two ways. Firstly, its members had to accept that their proposals for a peaceful resolution of the conflict by a court of arbitration had not been taken up by the governments involved. In addition, two of the movement’s leading exponents, Nobel Peace Prize laureates Albert Gobat and Bertha von Suttner, had recently died. Their deaths were harbingers of the disorientation and paralysis that seized the peace movement after the outbreak of war. In January 1915, the last joint session was held at the central office of the International Union of Peace Societies, in the International Peace Bureau in Bern. Due to disagreements over the assessment of breaches of international law committed in Belgium and Luxembourg, the session ended in a fiasco. Moreover, the Swiss Peace Society, with 6,000 members the largest pacifist group in Switzerland, was split between its French-speaking and German-speaking sections. While the latter mostly sympathised with the German Empire, its French-speaking members supported the Entente.

Humanitarian commitment

Despite the paralysis within the peace movement, many people wanted at least to contribute to alleviating the effects of the war, and large numbers of pacifists were involved in the humanitarian services. The Swiss Peace Society called on its members to make themselves available to the branches of the Red Cross and the International Prisoners of War Agency (AIPG) established by Gustave Ador, a National and Federal Councillor from Geneva. One of the key tasks of the AIPG was to collect information on the whereabouts and health status of prisoners of war and pass this information on to relatives. Over the years, the card file produced for this purpose comprised more than 4,805,000 index cards. Switzerland’s humanitarian services enhanced the country’s reputation and were of enormous benefit in justifying Switzerland’s neutrality, which the warring countries wanted neither to understand nor to accept.

Office of the International Prisoners of War Agency in Geneva. Photo: ICRC Archives

Women at work in an improvised uniform-making workshop. Photo: Swiss Federal Archives

New pacifist organisations and peace activists

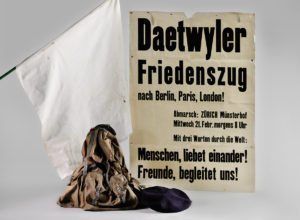

While certain sections of the population in the belligerent countries revelled in the euphoria of war, even in the first few months after the war broke out new pacifist groups were forming worldwide as a counter-movement to the conflict. The pacifists sought new ideas to ensure that future peace would be not merely temporary, but permanent. In Switzerland, the ‘Komitee zum Studium der Grundlagen eines dauernden Friedens’ (Committee to study the principles for establishing long-term peace), set up in October 1914, dedicated itself to this goal. During the war, the churches and women’s associations in particular became more involved in the politics of peace. The Swiss section of the ‘Frauenliga für Frieden und Freiheit’ (Women’s League for Peace and Freedom) considered that lasting peace could only be achieved if women were given the opportunity to shape progress in politics and society on equal terms. The demands of feminist activist Clara Ragaz therefore explicitly included voting rights for women. Recognition of the right to vote seemed all the more justified because women did valuable work for the state and society while many men were absent due to active military service. Max Daetwyler made headlines when, in protest against the war, he refused to take the oath of allegiance during mobilisation. In 1915, he founded the ‘Friedensarmee’ (Peace Army) in Bern, and the apostle of peace with the white flag became a world-renowned icon of pacifism.

Max Daetwyler’s backpack and white flag. Photo: Swiss National Museum

The Zimmerwald movement

Since Italy’s entry to the war in May 1915, Switzerland had been completely surrounded by belligerent states. The assumption, widely held in August 1914, that it would be only a brief war proved an increasingly forlorn hope the longer hostilities dragged on. General opposition to the war increased. In Zurich Willi Münzenberg, as head of the ‘Internationale Verbindung sozialistischer Jugendorganisationen’ (international union of socialist youth organisations – the IVSJO), organised a number of anti-war demonstrations. With the outbreak of war having brought the Second Socialist International to a conclusive end, National Councillor Robert Grimm succeeded, in September 1915, in assembling leading socialist opponents of the war in the remote Bernese village of Zimmerwald. To maintain secrecy, the peace conference had been announced as an ornithological gathering. The resolution hammered out by the socialists denounced the imperialist nature of the war, called for international proletarian solidarity, and demanded peace without annexations or war reparations. The ‘Zimmerwald Manifesto’, published on the front page of the Berner Tagwacht newspaper, attracted considerable attention not least due to its signature by German, French and Russian socialists – all members of belligerent states.