Around the world with James Cook

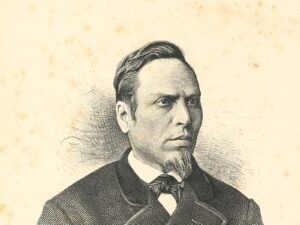

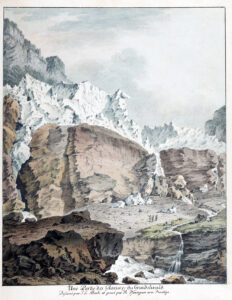

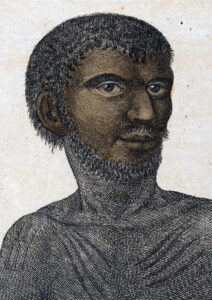

The Swiss-British artist John Webber (1751-1793) served as the draughtsman in Captain James Cook's third expedition to Oceania, Canada, and Alaska. Webber’s artwork captures a unique moment in time – the first encounters of the British with indigenous peoples from around the Pacific Rim.

Do just once what others say you can't do, and you will never pay attention to their limitations again.

Artist for James Cook’s Third Expedition (1776−1780)

Return to England & Impressive Legacy

Collections of Webber's works can be found in many cultural institutions, including the Bern Historical Museum in Bern, Switzerland, the British Museum in London, UK, the National Maritime Museum in London, UK, the Anchorage Museum in Anchorage, Alaska (USA), the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawaii (USA), the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington, New Zealand, and the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia.