The "Camino Español" through Switzerland

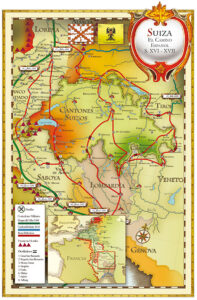

During the Counter-Reformation, Switzerland’s Catholic cantons cultivated strong ties with Spain to counter Protestant ambitions. The “Spanish Road” – a vital artery for the Spanish war effort during the Eighty Years' War – ran directly through Switzerland for a brief period of time.

Ludwig Pfyffer and the Spanish Alliance

Poner una pica en flandes

El Camino Español de Suizos and the Global Hispanic World