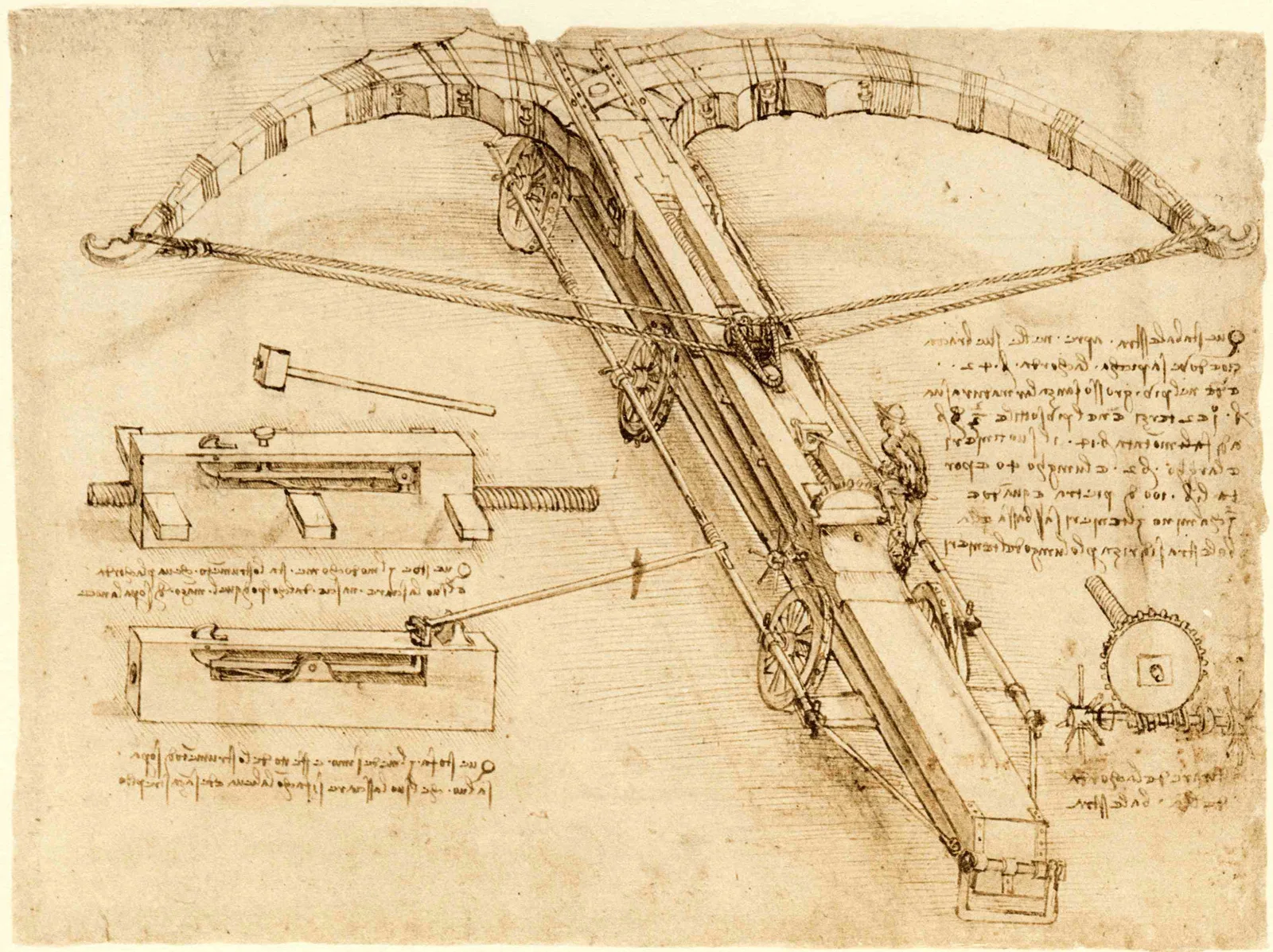

The crossbow: A weapon for assassins and freedom fighters

Wilhelm Tell’s crossbow is, so to speak, the national weapon of Switzerland. In actual fact the weapon has its origins in ancient China, and although superior to the bow the crossbow didn’t have the best reputation.