Aïssé – from slave to socialite

Her story sounds like a fairy tale from One Thousand and One Nights, but it’s true. Originally from the Caucasus region, Aïssé (1693/4-1733) was sold on the slave market as a child and grew up in Parisian high society. She fascinated her contemporaries, inspired novelists and, through her letters, entered posterity as a literary figure of the Enlightenment.

Aïssé de la Grèce épuisa la beauté

Elle a de la France emprunté

Les charmes de l’esprit, de l’air et du langage

Pour le cœur, je n’y comprends rien

Dans quel lieu s’est-elle adressée

Il n’en est plus comme le sien

Depuis l’age d’or ou l’AstréeJacob Vernet, 1788

Haïdé, to use her original name, was born sometime in 1693 or 1694 in the north-western Caucasus; the exact date of her birth is unknown. The girl came from a region that today roughly coincides with the Russian Republic of Karachay-Cherkessia. According to tradition, she is said to have been the daughter of a Circassian chief.

After Aïssé’s father was defeated and killed in battle by the Turks, the little girl, then aged about five, was placed on the slave market in Constantinople, where she was offered for sale as a Circassian princess. With sale into a seraglio the most likely outcome, her fate seemed sealed until an emissary of the French King Louis XIV, the Comte Charles de Ferriol (1652-1722), became aware of the girl. He purchased Haïdé for 1500 livres, freeing her from the clutches of the slave traders, presumably with the intention of raising her to be his lover later on.

The northern Caucasus around 1700. Map by Guillaume de L’Isle (1675-1726). Source: David Rumsey Map Collection

Ahmed III receiving the French ambassador Charles de Ferriol (click to enlarge). Painting by Jean-Baptiste Vanmour, around 1724. Source: Wikimedia

From Constantinople to Paris

Together with Haïdé, Ferriol returned by sea to his native France in 1699. At the end of the two-month journey, he had the girl baptised in Lyon with the name Charlotte Elisabeth Aïssé. Arriving in Paris, he handed her into the care of his 25-year-old sister-in-law, Marie-Angélique. A year later, he returned to the Ottoman Empire as French ambassador, a role in which he was to remain until 1711.

Ferriol’s sister-in-law raised Aïssé, as she was known from then on, as her own child and gave her an education befitting her social standing: first with a tutor alongside Marie-Angélique’s own sons, and then at a convent school.

Between the ages of 16 and 17, Aïssé was introduced into Parisian society. Marie-Angélique held a popular salon frequented by philosophers and writers, including famous names such as Voltaire and Montesquieu. Aïssé became a regular at this salon, and soon established herself as a star attraction. Not only was she beautiful, poised and cultured, but with her Eastern origins, exotic charms and adventurous history she piqued the curiosity of her contemporaries.

This painting by Anicet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier (1743-1824) depicts a scene in the literary salon of Madame Geoffrin (seated on right, facing the viewer). Lekain, an actor (centre, dressed in red), is reading Voltaire’s tragedy L’Orphelin de la Chine. The author himself is present in the form of a bust. Source: Wikimedia

A climate of burgeoning orientalism

In the climate of burgeoning orientalism of 18th century Europe, with a translation of One Thousand and One Nights having recently appeared in France, a young, attractive woman who had been ‘snatched from the hands of heathens’ caused a sensation. From that time on, the ‘Orient’ was not only viewed as a hotbed of despotism, irrationality and erotic depravity, but also romanticised as the home of the natural and pristine, the mythical and the utopian. Orientalism flourished in the form of a voguish fascination with anything exotic. This image became apparent in music, the fine arts and literature too, as reflected, for instance, in Montesquieu’s work Lettres persanes in 1721. This fascination with the mysterious East lasted into the late 18th century – one need only think of Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio (first performed in 1782).

A foster father with demands

In 1711, 64-year-old Charles de Ferriol returned to Paris. Aïssé was now of marriageable age, and there was a queue of admirers. Even the married Philippe II of Orléans, known for his debauchery, is said to have been interested in an amorous adventure with the pretty Aïssé. Contrary to the social code of the time, however, she rejected the Regent’s advances. Nor was there any shortage of offers of marriage. But as far as Ferriol was concerned, none of these people was good enough for his ward, whose legal status he never changed. Instead of recognising and adopting his foster daughter as such, he insisted that she address him by the Ottoman honorific ‘Aga’.

The reason for this may well have lain in the assumption expressed earlier, that Ferriol had hardly bought Aïssé out of any fatherly concern for her welfare. His true ulterior motives became increasingly clear in the personal demands he made of the much younger woman. These culminated in his eventually joining the ranks of suitors seeking Aïssé’s hand. In a letter, he tried to persuade her to take him as her husband: «Vous auriez été la maîtresse d’un turc qui aurait peut-être partagé sa tendresse avec vingt autres, et je vous aime uniquement […]». But his advances were unsuccessful. And she was finally freed from them altogether after Ferriol suffered a stroke which kept him bed-ridden until his death in 1722. Aïssé tended to him to the last, for which he rewarded her richly in his will.

Aïssé in a fine silk and lace gown with flowers and a pearl in her grey powdered hair. The painting is attributed to the Parisian painter Nicolas de Largillière and is undated, around 1720. Collection of Jegenstorf Castle

Love affair with a man of God

At that time, Aïssé was already involved in an intimate relationship with the Chevalier Blaise-Pascal d’Aydie (1692-1761). So as not to harm his career, she did not wish to marry him. As a member of a religious order, he would have had to renounce his oath, leave his order and – since he was not the first-born, and therefore privileged, son of the family – he would then have had to live in quite humble circumstances. So their love remained hidden; only a close circle of friends was entrusted with the secret, and covered for the couple’s secret trysts.

The intimate relationship between Aïssé and d’Aydie resulted in a pregnancy, which would have meant a social scandal. For this reason, Aïssé spent the last few months before the birth away from Paris. Aïssé secretly gave birth to her first and only child, a girl, in an outlying district of the city in 1721. She was purported to be in England staying with one of her friends, the wife of Lord Bolingbroke. It was this friend who first took the baby girl to England after her birth, and later returned with her to France. There, she took the baby to the Abbey of Sens and claimed it was her husband’s niece.

Aïssé’s daughter was raised at the Abbey under a false identity, as Célénie Leblond – the girl had blonde hair. Aïssé and d’Aydie endeavoured to maintain contact, despite difficult conditions due to the secrecy, and visited the girl several times a year. But Célénie found out that the pair – as she saw them, a kind lady and a generous gentleman – were her parents only after the death of her mother. Aïssé died of tuberculosis in 1733, not yet 40 years old. Célénie’s father then officially recognised her as his biological daughter, took responsibility for her care from then on and in 1740 married her to a member of the landed gentry, with whom she lived at Chateau Nanthiat.

Aïssé reading, graphic (engraving) by Gustave Staal, Paris, 1881.

Literary legacy

The fact that we know today about Aïssé’s existence, life and eventual fate is thanks primarily, as is common in the female historical tradition, to Aïssé herself. From 1726 until her death in 1733, Aïssé maintained an intensive correspondence with her Genevan friend ‘Mme Calandrini’ (Julie Clanderini, née Pelissary), although the two women only met twice, once in Paris and once in Geneva.

In her letters, in addition to personal matters Aïssé reported to her older friend on the social life in Paris during the early years of the reign of King Louis XV, visits to the theatre, new books and social scandals. Aïssé seemed to put great stock in the moral teachings of her motherly pen pal, but despite Calandrini’s advice she never broke up with her Chevalier, although she tried to.

Luckily, Aïssé’s letters – originally probably 40 to 50 separate items, of which only a few still survive today – ended up, through Clanderini’s grandson, in the hands of Voltaire in 1758. Voltaire, who had become acquainted with Aïssé in her youth and, by his own admission, had also fallen in love with her, considered the letters authentic and worthy of publication.

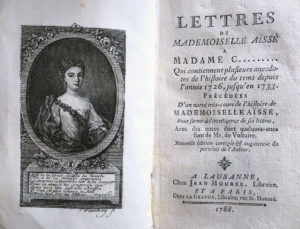

But it was not until 1787 that the first edition of Aïssé’s letters, with personal comments by Voltaire, who had died in 1778, was published in Paris. This first edition was followed a year later by a further volume published in Lausanne, edited by Jacob Vernet. In this, and also in a later edition from the 19th century, an engraved portrait of the author, with a verse by Vernet, adorns the frontispiece (first page).

Lettres de Mademoiselle Aïssé à Madame C[alandrini] qui contiennent plusieurs anecdotes de l’histoire du tems depuis l’année 1726 jusqu’en 1733, 1788 edition, Lausanne. The portrait of the author with a verse by the editor, Jacob Vernet, adorns the frontispiece. Aargau Cantonal Library (Aargauer Kantonsbibliothek). Photo: Jegenstorf Castle

Living on in art and literature

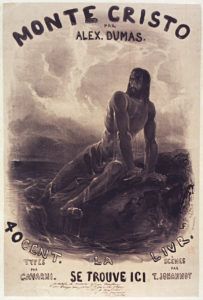

Aïssé lives on not only in the famous published letters, but also in French literature: her biography inspired the literary figure of Haydée in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte Cristo, published in serialised form between 1844 and 1846, which captured the spirit of the age and is still considered a classic of world literature. Aïssé’s relationship with the Comte de Ferriol was worked into the novel. For other literary works too, such as Voltaire’s tragedy Zaïre (1732) and Antoine-François Prévost’s novel L’Histoire d’une Grecque moderne, Aïssé’s life and fate were an important source of inspiration.

Poster of Louis Français for The Count of Monte Cristo, 1846. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Haydée at the slave market.

Haydée and the count in Paris. Engraving in the first edition of Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte Cristo (1846).

Only a handful of portraits of Aïssé exist. A beautiful painting, probably produced around 1720, is kept in the collection of the Jegenstorf Castle Foundation. Aïssé was represented with this portrait and her story in the special exhibition ‘Our women. Lived, served, protected in the Castle’, which ran until 14 October 2018. She was one of 27 women from the past few centuries whose biographies form a tour d’horizon of the history of women in Switzerland, with a special emphasis on society and family.