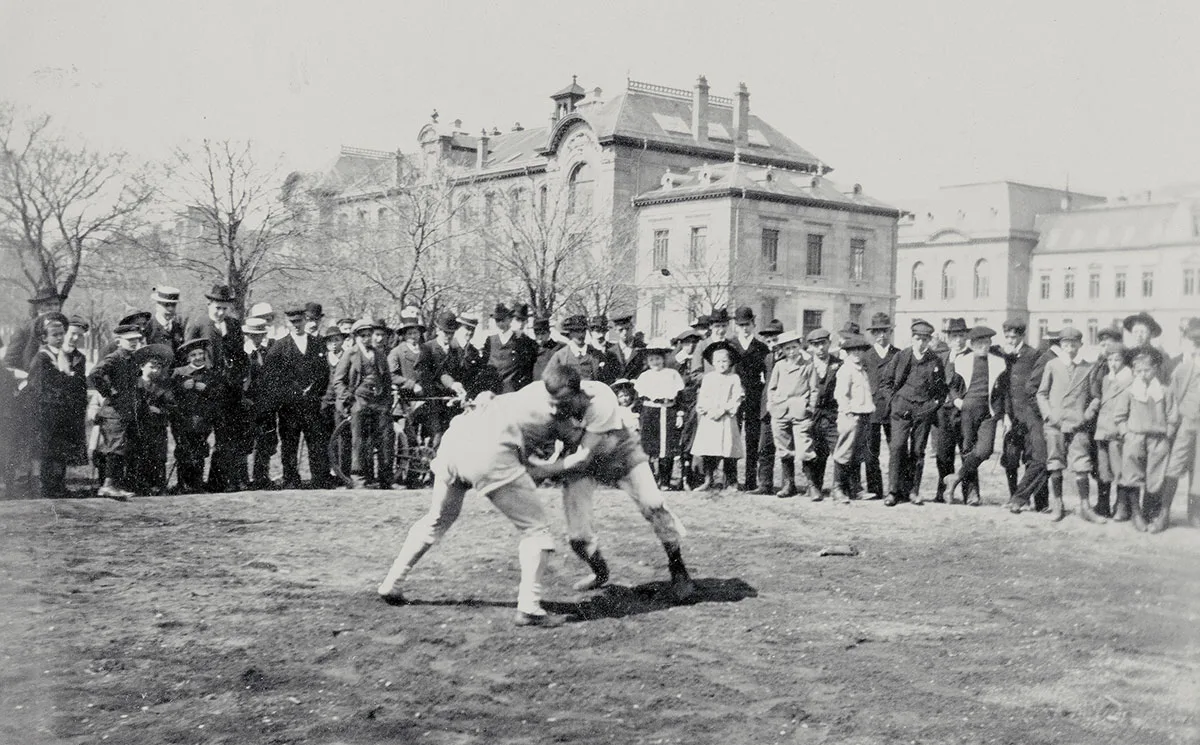

Rural sport, or urban commercial activity?

We mentally associate ‘schwingen’, traditional Swiss wrestling, with brawny herdsmen fighting a clean fight in idyllic mountain surroundings. But it’s not as straightforward as that. Urban dwellers played a bigger role in popularising the sport than one might think.

Turning to nature helps schwingen

Review of the Eidgenössische in Zug, 2019. YouTube / SRF

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch