The Confederation's policy of concordance

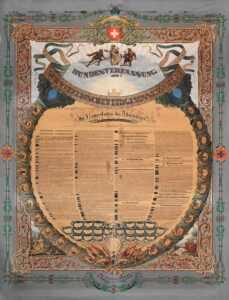

The Swiss Confederation has had a constitution since 1848. Yet the history of this legal document, which is still in force today, dates back much further. It would be almost impossible to imagine the federal state in its current form without this historical prelude.

Policy of concordance

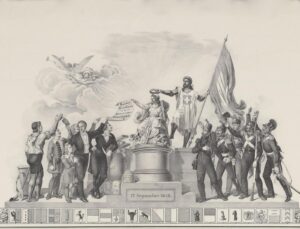

Attempts to revise the Federal Treaty, and the Sonderbund War

The genius of the Federal Constitution