Casting light on relief map shading

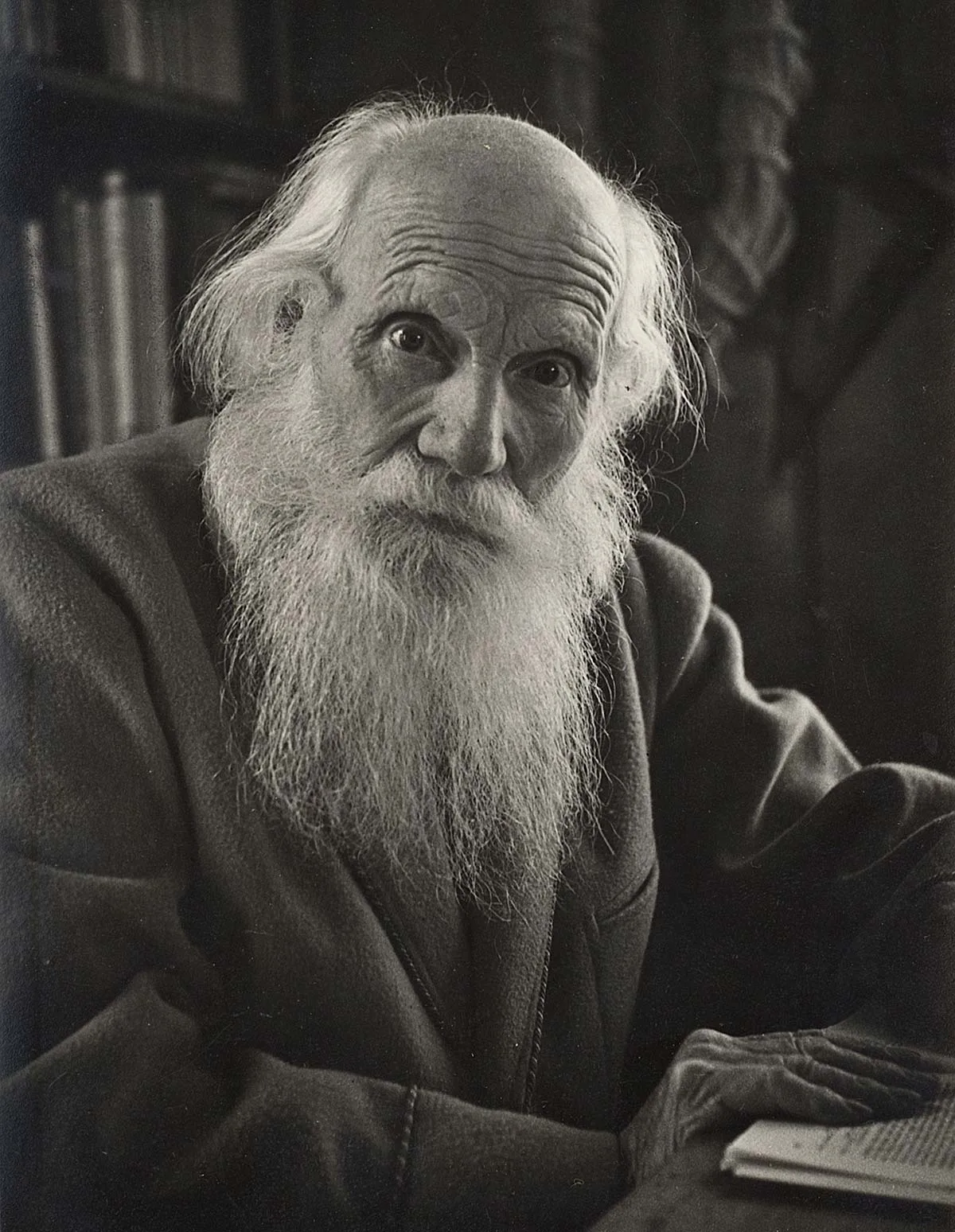

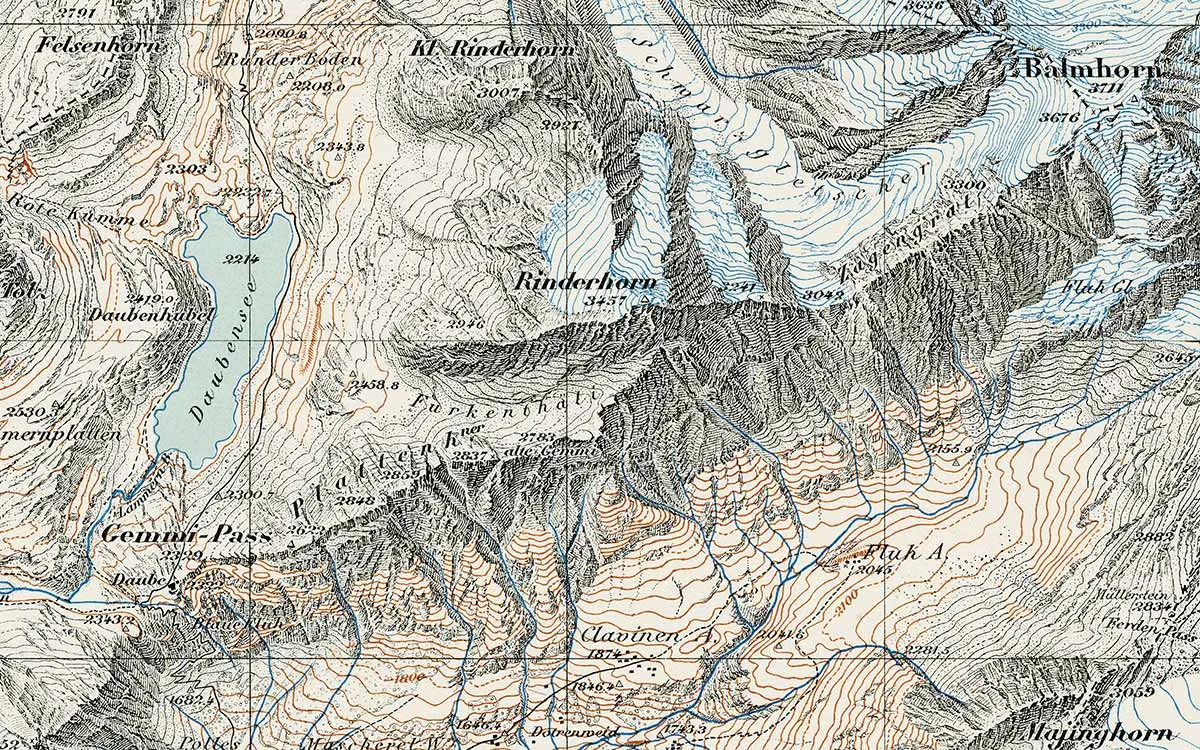

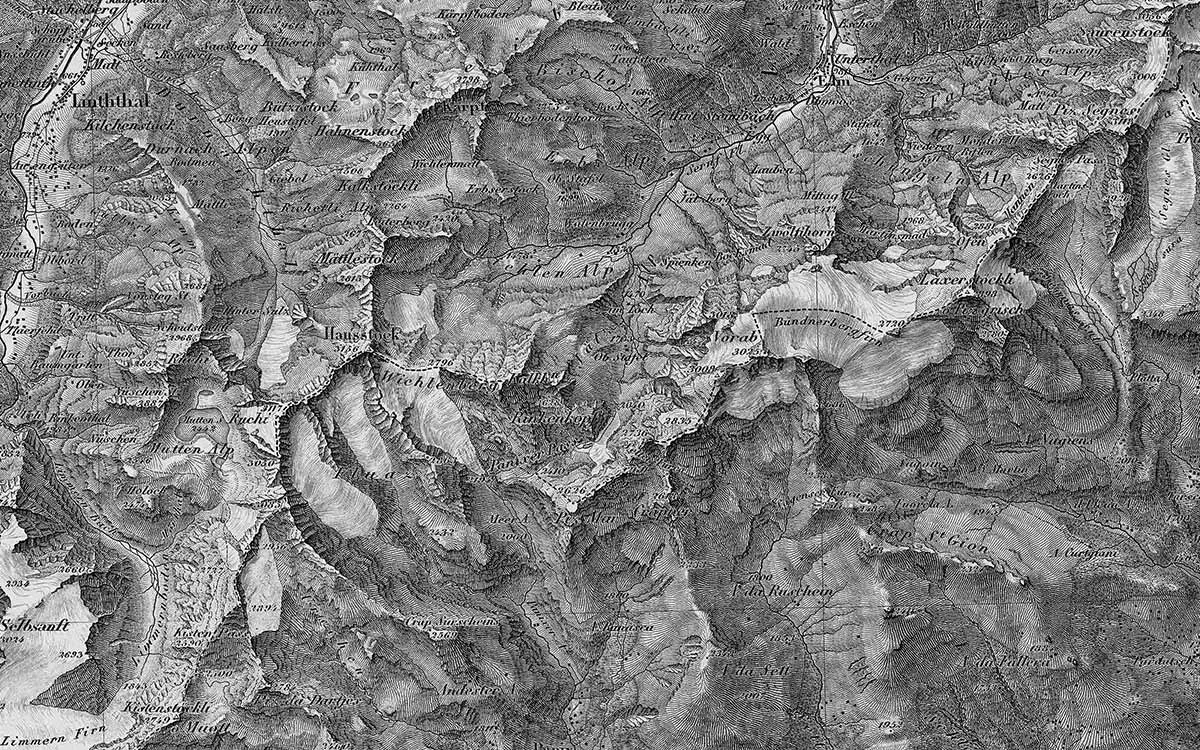

In 1927, geologist Albert Heim clashed with cartographers at the Federal Office of Topography as he was convinced that their relief maps of Switzerland were depicted in the wrong light. Heim believed that the light source on maps should correspond to natural sunshine.

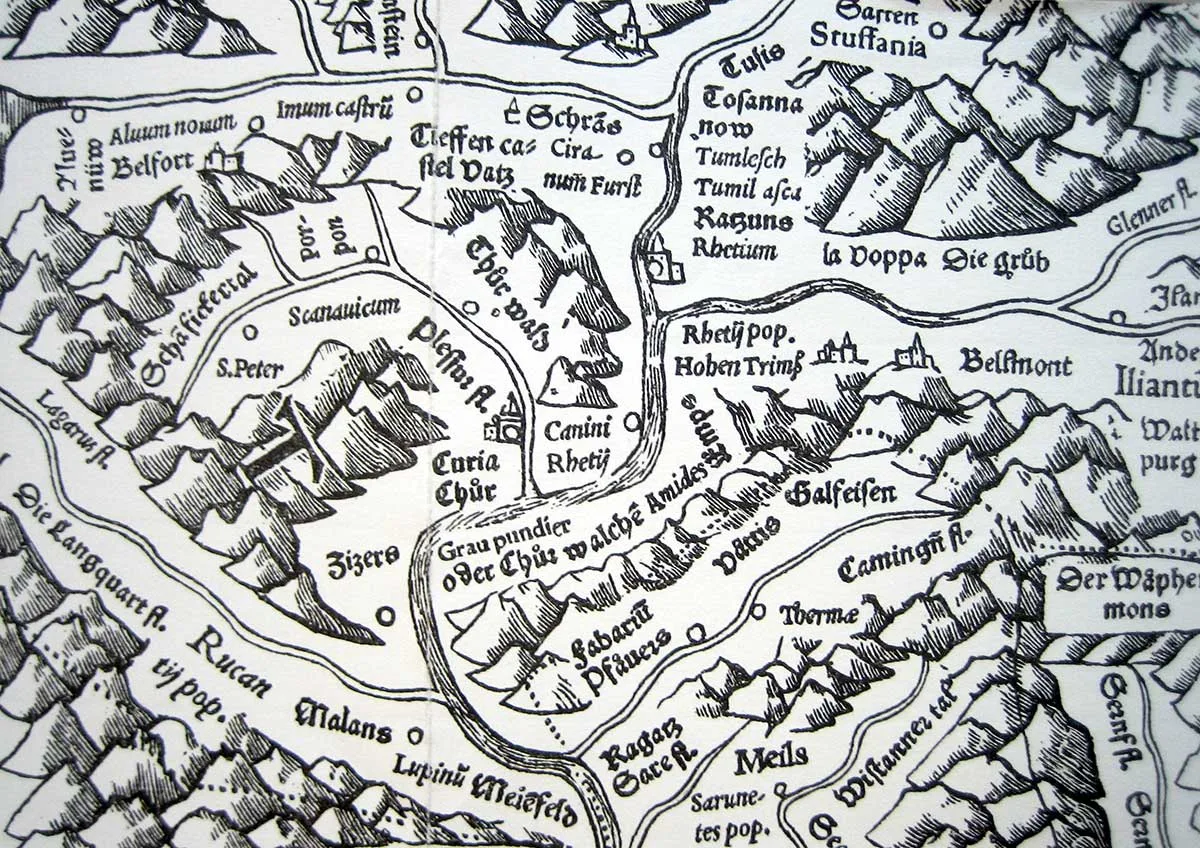

It pains me to see the warm vineyards and villages on the sunny side of the main Valais valley on the north side of Lake Geneva and the heavily-farmed sunny slopes of the north side of the Anterior Rhine Valley in the shade, while the wooded slopes on the shady side are bathed in blazing sunlight.

Why are most maps illuminated from the northwest?

Space and time

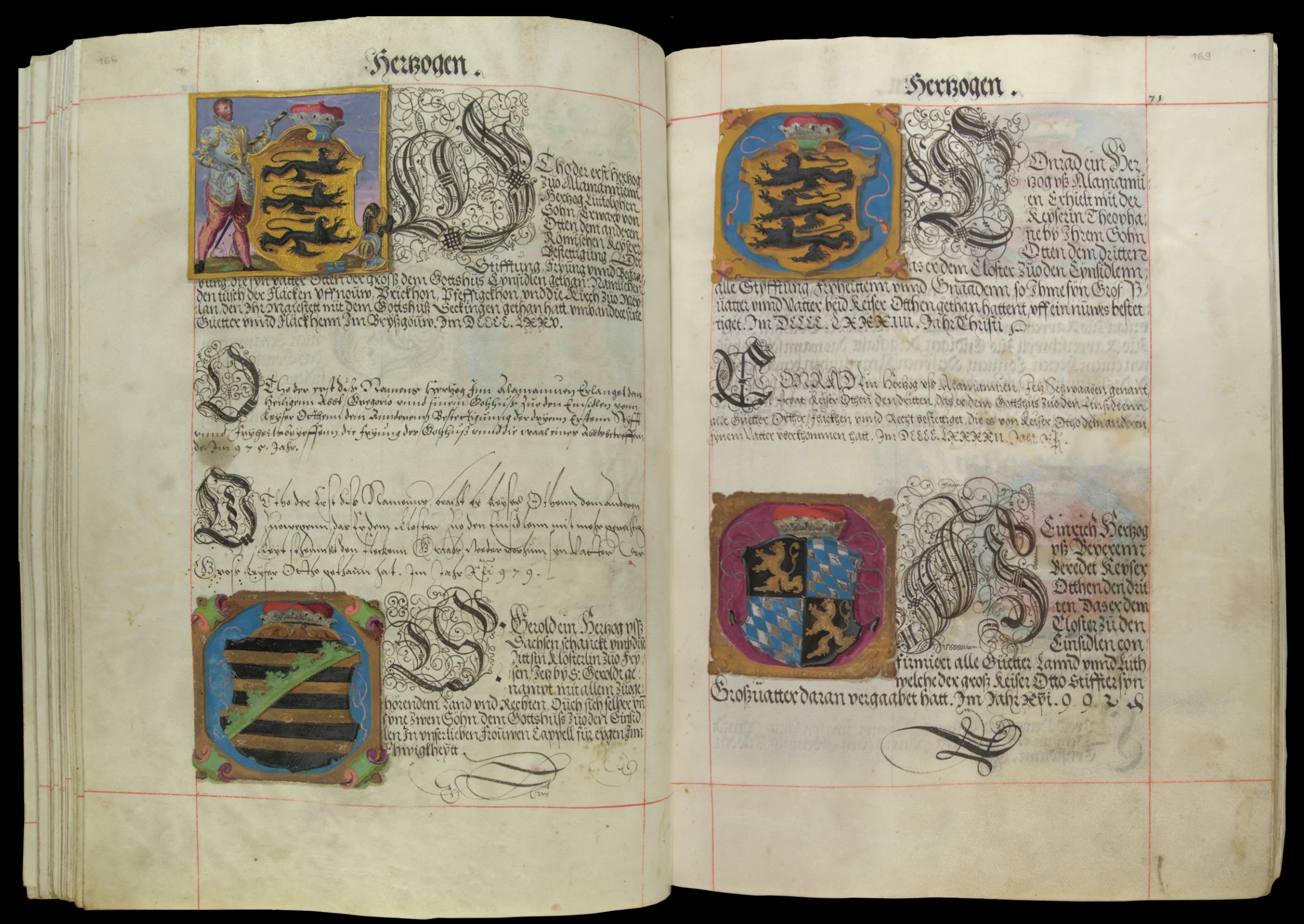

This article was originally published (in German and French) on the “Space and time” website of the Federal Office of Topography (swisstopo), where readers can regularly discover thrilling chapters from the history of Swiss cartography.