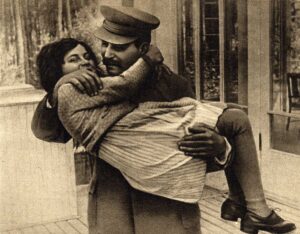

Frau Staehelin, Stalin’s daughter

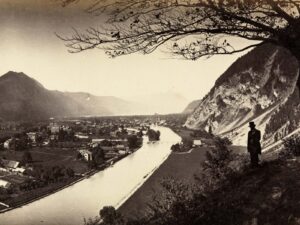

In spring 1967, Stalin’s daughter travelled to Switzerland. In the middle of the Cold War. The story of a diplomatic high-wire act.

Visit for ‘rest and recuperation’

The interests of the state versus individual freedom

Press conference given by Svetlana Alliluyeva on arriving in the United States in April 1967. YouTube / British Pathé

This article by Thomas Bürgisser was first published in the WOZ newspaper in December 2011. It is based on documents from the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland (Dodis) collection with additional material from another WOZ article of March 2017 and further Dodis documents.