Switzerland as Haven of Political Asylum

In the course of redrawing the political map of Europe at the Congress of Vienna in 1814/15, the Great Powers assigned Switzerland a clear role: the small alpine country at the heart of the continent was to form a peaceful hub acting as a stabilizing buffer between the monarchies surrounding it. When the Swiss Confederation unilaterally changed its system of government in 1847/48 and became a liberal federal state, the Vienna signatory powers regarded this as an affront and a breach of the reigning agreement. Saint Petersburg suspended all diplomatic relations until 1855. The ideological difference between the Tsarist autocracy and the new Swiss republic widened and, not least with regard to the question of asylum, clashes between the two political cultures became more frequent.

Even prior to 1848 Switzerland had been an attractive haven for political refugees, not only because of its central location and tradition of neutrality but also due to its growing sense of a liberal national identity since the 1830s. Not only its avowal to democracy and free trade but also its resistance against despots and an almost mythical notion of a tradition of granting asylum reaching back to the Middle Ages increasingly shaped the country’s political understanding of self. In face of outward adversity, the nascent federal state came to regard its right of granting political asylum almost as a touchstone of national sovereignty. The Tsarist regime reacted to this with growing irritation. Keen to keep its subjects under control, the regime, with support from Prussia and Austria, had coerced the Swiss Assembly already in 1823 to step up its measures against foreigners by having it issue a strict clampdown on the press and foreign citizens. The Tsarist government saw in the new liberal Switzerland of 1848 a dangerous revolutionary flashpoint. It had Russian refugees in Switzerland shadowed and Russian secret agents occasionally even committed acts of sabotage against the political infrastructure set up by the refugees.

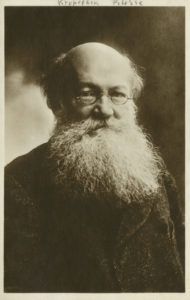

Pjotr Kropotkin, undated. Photo by Nadar. International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

The Swiss Federal Council tried to contain the damage as best as it could. In 1873 it signed a bilateral extradition treaty and offered to investigate political actions more thoroughly as to any potential criminal background – such as in the case of the shady revolutionary Sergey Nechayev. Several anarchists were expelled, among them in 1881 Pyotr Kropotkin who had issued the journal Le Révolté in Geneva since 1879. Several persons were banished in one sweep after a number of Russian nationals had been injured while tinkering with a self-made bomb on the Zürichberg in 1881. In that same year the Swiss authorities established the office of Federal Public Prosecutor.

Switzerland introduced a more restrictive practice of political asylum during the First World War, culminating in the establishment of the Federal Office of Immigration Policing in 1917. However, all in all, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries this had no immediate effect on the fact that law-abiding refugees had little to fear from the Swiss authorities. There was no formal asylum procedure yet, and extradition to a foreign government for alleged political actions remained, by and large, taboo.

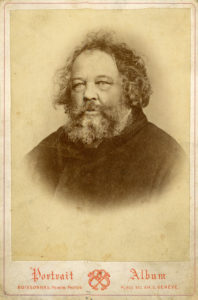

Mikhail Bakunin, around 1860. International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

Kolokol, journal, Geneva 1866, reprinted in 1964. Universitätsbibliothek Basel.

Georgi Plekhanov, undated. International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

Together with France and Great Britain, Switzerland was one of the main host countries for revolutionary émigrés seeking protection from Tsarist persecution. We can distinguish between three categories of political refugees. For one, we have national the freedom fighters resisting Russian occupation of the territory of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Following the failed revolts of 1830/31 and 1863/64, thousands of Polish refugees fled to the West – 2,000 of them to Switzerland after 1863. Here they met with considerable sympathy, especially from within democratic and liberal circles. After the January revolt of 1863/64, Polish committees were established in more than twenty cantons, and in 1870 even a Polish national museum was opened in the Castle of Rapperswil.

The second category of political refugees includes individual dissenters who saw in Switzerland a haven of free expression and regarded it as an ideal place to publish their political writings. Probably the most prominent among these was the writer and thinker Alexander Herzen who was forced to flee from the French police in 1849 and came to Switzerland where he became a citizen of Châtel (Burg) near Morat in 1851. Together with Nikolay Ogarev he issued the revolutionary newspaper Kolokol (The Bell) which was printed in Geneva as from 1865. Herzen represents an older generation of political refugees who, over time, lost touch with the developments in Russia. Quite a different kettle of fish in this sense was the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin who, after 1840, lived off and on in Switzerland; he was a great admirer of the young generation of revolutionaries and had a strong backing of supporters until his death in 1876.

Here we come to the third and most prominent group of political refugees – the above-mentioned young generation of revolutionaries who began settling down in Switzerland in the 1860s in increasing numbers. Many of them had taken part in student revolts in Russia or had supported acts of social revolutionary agitation. They were not so much interested in national liberation as in the radical transformation of the reigning social order. Unlike the former dissenters they retained strong links to the underground movements back home in Russia. Moreover, their approach went far beyond mere abstract reflection and relied on pragmatic, potentially violent action. They were divided into many subgroups with varying attitudes towards the role of terror.

The supporters of the revolutionary organization Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will), responsible for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, published a journal by the name of Vestnik Narodnaya Volya (Messenger of the People’s Will) in Geneva from 1883 to 1886. In its wake came the representatives of the terrorist underground party of Social Revolutionaries who were not adverse to terrorist tactics. In 1906 Switzerland even experienced an assassination attempt, namely when the young Russian Tatyana Leontyeva shot a pensioner in the Grand Hotel Jungfrau in Interlaken, mistaking him for a former Russian minister of the interior. In contrast, we have a circle of revolutionary intellectuals around people like Georgi Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod and Vera Zasulich who had already formed in Russia in 1879 and who opposed terrorism. They went on to establish the Marxist political organization called Gruppa Osvobozhdenie Truda (Emancipation of Labour Group) in Geneva in 1883, a predecessor of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. The latter published its journal Iskra (Spark), among other places, in Geneva.

All in all, the political émigrés of this third category met with favourable conditions in Switzerland. Unlike the Polish freedom fighters they did not actually enjoy great solidarity among the Swiss population but they, too, benefited from the freedom their host country offered and also profited from a well-organized colony of critical fellow Russians.

Iskra number 18 from March 1902. Universitätsbibliothek Bern.