Tourists, Convalescents, Students and Soldiers

After the fall of the Tsarist regime in the February Revolution of 1917, many of these political émigrés returned to Russia – among them Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. In his exile in Switzerland during the First World War, Lenin had elaborated on his political programme. At the international socialist peace conferences in Zimmerwald (1915) and Kiental (1916) Lenin had strongly advocated proletarian world revolution and propagated the idea of waging a civil war against the reigning government at home. His radical demands, however, found little resonance among the conferences’ predominantly pacifist participants to which also the Swiss social democrat Robert Grimm belonged. But Lenin found at least one strong Swiss supporter in the person of Fritz Platten who, among other things, was also decisively involved in organizing Lenin’s journey home in the so-called sealed train in April 1917.

Within the Russian colony in Switzerland, the Bolsheviks’ radical demands led to increased dissent and polarization and, after the October Revolution, to a bitter struggle for supremacy. In May/June 1918 the Bolshevik delegation under Jan Berzin succeeded in ousting the resident Russian embassy and establishing itself as the true and only representative of the new Russia in Bern, at the same time using the occasion to step up its propaganda activity. In November 1918, on the eve of the general strike in Switzerland, the Soviet Mission was expelled from the country.

However, political refugees were not the only people to undertake the long journey from Russia to Switzerland. As early as the eighteenth century, Russian aristocrats had been attracted to the beauty of the alpine landscape, not least through the works of Russian poets and writers who fuelled the myth of the blissful Swiss mountain world, a prominent example being the travel diaries of Nikolay Karamzin, a revered poet and historian. In the nineteenth century, thousands of Russian patients, most of them suffering from tuberculosis, flocked to the hotels and sanatoriums in the Swiss mountains, even prompting the Russian government to establish a permanent consular mission in Davos in 1911.

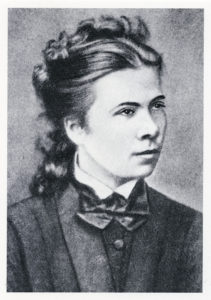

From roughly the 1860s onward, the sick were joined by a large number of Russian men and above all women seeking higher education at universities in Switzerland. Well into the twentieth century, women in Tsarist Russia were barred from university, making Nadezhda Suslova the first Russian woman to be awarded a Doctor of Medicine degree at the University of Zurich in 1867. Other famous women to study at Zurich University were the later revolutionary leader Vera Figner and the Polish-born social democrat Rosa Luxemburg. In view of the apparent interweavement of student and revolutionary activities, the Tsar prohibited Russian female subjects from studying in Zurich, to the effect that many them simply switched to other Swiss universities. After the turn of the century, a second “wave of Russians” flooded the Swiss institutions of higher education: in the winter semester of 1906/07 more than 2,300 Russian subjects were studying at Swiss universities, 1,500 of them women. This meant that the Russians made up thirty-six per cent of the Swiss student population. Taking only female students into consideration, Russian women accounted for roughly three quarters of the student population in those early years of the twentieth century. The majority of them chose to study medicine.

According to a census of 1910, approximately 8,500 people from the European part of Russia were living in Switzerland at that time, roughly half of them in Zurich and Geneva. After the outbreak of the First World War, many of them sought to return home. At the same time, scores of new Russian men and women set out for neutral Switzerland, among them people who had been living in what had become German or Austrian enemy territory, as well as roughly 3,000 soldiers, many of them deserters and former POWs, in search of a safe place to stay. Like the students, they were wooed by activists of all political factions. Thus, they inevitably became part of a highly politicized expat community that followed spellbound the upheavals that were radically reshaping their Russian homeland.

Robert Grimm, approximately 1920. Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv, Zurich.

Fritz Platten, approximately 1925. Schweizerisches

Sozialarchiv, Zurich.

Nadezhda Suslova, undated.

Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv, Zürich.