Computerspielemuseum Berlin

Learning by playing

A brief history of digital gaming in the classroom: from ‘The Oregon Trail’ to ‘Assassin’s Creed Educational Mode’.

In 1973, the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium (MECC) was founded in Minnesota, then one of the centres of technology in the USA. The goal of the organisation, a public sector enterprise, was to promote the use of computers in education. Ten years later, more than 70% of schools in Minnesota were accessing the Time Sharing service established by MECC, which made nearly 1,000 programmes available for classroom use. One of MECC’s first successful educational games – and one that is still played today – was ‘The Oregon Trail’ (1971), in which players follow the settler route through the Rocky Mountains and navigate the trials of everyday settler life.

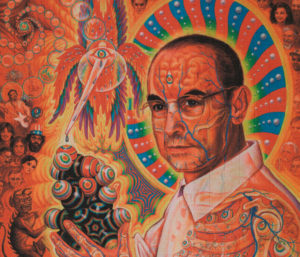

On the ‘Oregon Trail’. The game is available free online.

classicreload.com

In addition to MECC, a number of other companies also recognised the potential of digital games as teaching materials. For example, the sleuthing educational game ‘Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego?’ (1985) by Brøderbund found its way into classrooms around the world, along with various titles from The Learning Company with very telling names such as ‘Reader Rabbit and the Fabulous Word Factory’ (1983) and ‘Addition Magician’ (1984). A world-wide market with an unbroken run of success developed out of these early titles. Motivation and the visual representation of content, the protected nature of the learning environment, and the firm rooting of the games in the everyday life of schoolchildren make digital games a very effective teaching tool.

At the same time, the home computer was becoming established as a learning device. While many of the early educational games were played on computers such as Apple II and Atari 600XL, Britain’s BBC radio broadcaster started its Computer Literacy Project in the early 1980s. This consisted of the BBC Micro microcomputer, specially developed by Acorn Computers for the project, and a television series called ‘The Computer Programme’, which covered different programming skills each week. The BBC Micro very rapidly took hold in schools; soon, 80% of British schools were using a BBC Micro.

In addition to teaching, educational games are also used in medicine. With the first-person shooter game ‘Re-Mission’ (2006), young cancer patients were taught in an entertaining way how individual medications affected their disease and the progress of their treatment.

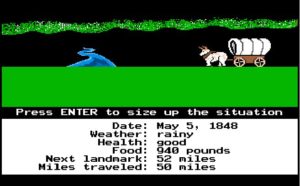

[siteorigin_widget class="SiteOrigin_Widget_Image_Widget"][/siteorigin_widget]

Ian McNaught-Davis, moderator of the BBC television series ‘The Computer Programme’, with the BBC Micro.

BBC.co.uk

From entertainment medium to teaching tool

As long ago as the early 1990s, both educational games and games developed for the general market were widely used in foreign language teaching. Due to the high proportion of text, interactive fiction, text and graphic adventures were a popular means of exposing learners to realistic textual content. With the advent of online gaming, these genres were replaced primarily by MMORPGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games) such as ‘World of Warcraft’ (2004), which are still considered a good complement to foreign language teaching, since language is essential as a communication tool and the enjoyment of the game lets learners quickly leave behind their linguistic inhibitions.

Due to their increasing acceptance, the use of digital games in teaching has fundamentally changed, especially in the last 10 years. For example, gameplay environments such as ‘Minecraft’ (2009) and development environments such as ‘Twine’ (2009) hone players’ creativity and ability to express themselves.

Even history lessons are increasingly recognising digital games as a learning resource. The educational mode of ‘Assassin’s Creed Origins’ (2017), for example, allows players to go on virtual excursions to ancient Egypt without leaving the classroom. In addition to historical and cultural learning content, digital games are also used in the classroom as aesthetic products and works of art. Since the early 2010s, narrative games have increasingly been incorporated into German lessons in the context of literary aesthetic learning, and their specific forms of narration examined.

The non-violent Discovery Mode in the game ‘Assassin’s Creed Origins’ allows players to visit the Great Pyramid of Giza 4,500 years ago.

YouTube

Digital games are a highly relevant medium for children and teenagers. For teaching, however, they’re not just a resource; they’re also a great opportunity for teachers to learn something from their pupils and to give them self-confidence by showing a benevolent interest in their hobby, a social and discourse-defining medium.