Showdown with the Habsburgs

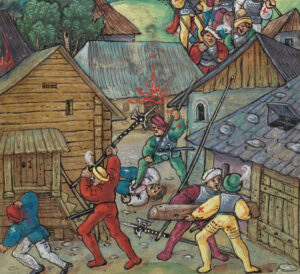

In the Swabian War of 1499, the Old Swiss Confederation fought against Habsburg Austria and the Swabian League. The cruel and devastating victory of the Swiss underscored their independence within the Holy Roman Empire.

Prelude, Provocation & International Tensions

When they start out to war they swear a solemn oath that every man who sees one of his comrades desert, or act the coward in battle, will cut him down on the spot, for they believe that the courage and persistence of warriors is greater when they, out of fear of death, do not fear death…

Short War & Swiss Victories

…In the capture of prisoners there is more humanity to be found among Turks and Bohemians than among the Swiss.

Peace of Basel and Legacy

Parts of the booty from the Swabian War can now be found in the collection of the Swiss National Museum, such as an equestrian flag of Count von Sonnenberg and a shield for swordsmen. Swiss National Museum