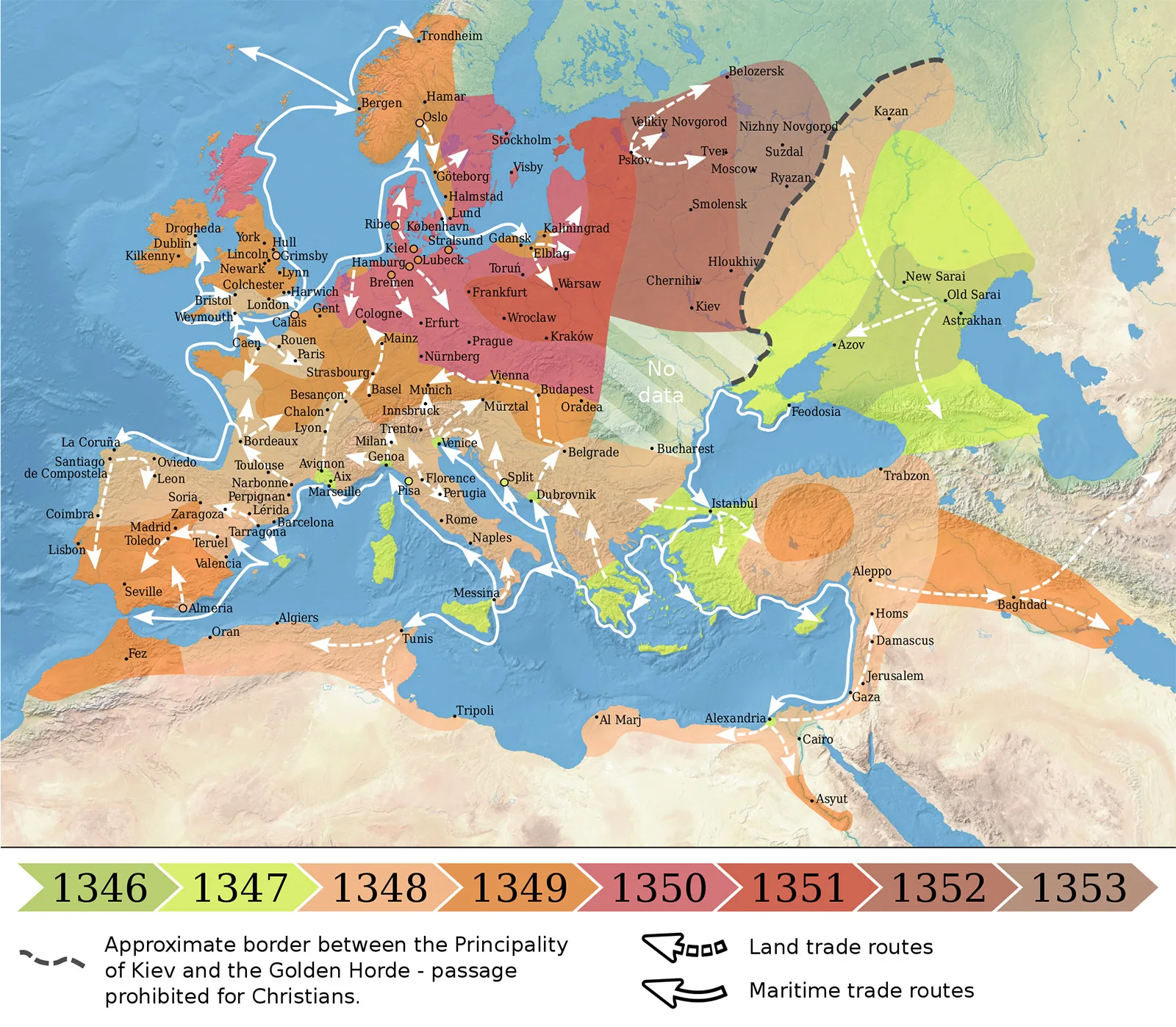

How the Great Plague changed the world

The plague epidemic in the Middle Ages, and its aftermath, readily invites comparison with the coronavirus pandemic. In his fascinating account of the ‘Great Plague’, however, historian Volker Reinhardt also warns of the limitations of such comparisons.

A quantum leap in the development of medicine

Plague 101 with National Geographic YouTube / National Geographic

Far-reaching social upheavals

Politics and religion put to the test

A zoom lens on hot spots and flashpoints

Basic pattern for dealing with an epidemic

The power of the plague – How the Great Plague changed the world – 1347 – 1353

Volker Reinhardt, Verlag C.H. Beck, Munich 2021.

256 pages with 25 illustrations and a map. Currently available in German.