The battle of Grandson

The Battle of Grandson is one of the most celebrated and decisive battles in Swiss history, and a key battle of the Burgundian Wars (1474–1477). On March 2, 1476 at Concise in present-day northwestern Switzerland, the Swiss Confederates dealt the Burgundians a crushing defeat from which they would never recover. For the Swiss, Grandson signalled their emergence as an integral player in wider European affairs. It is popularly remembered as the battle in which the Swiss won the “Burgundian booty,” which enriched the soldiers who fought in the battle.

Dreaming of the creation of a kingdom to rival France and the Holy Roman Empire, set between the North Sea and the Mediterranean, Charles the Bold was a despot eager to secure a promising future for Burgundy built on political reform and military conquest. The son of Philip the Good and Isabella of Portugal, he had a noted interest in statecraft and in warfare, and he witnessed firsthand his father’s efforts to strengthen and consolidate his rule over his heterogeneous and ethnically diverse domains, which stretched from Picardy and Holland in the north to the shores of Lake Geneva in the south. Burgundy was the richest region in Europe outside of Italy, and Charles harnessed the wealth of his dominions to create an effective internal administration and employ costly foreign mercenaries from England and Italy. Charles utilized his newly accumulated powers in his campaign against Louis XI of France in the late 1460s and to put down the Revolt of Liège in 1468. With peace restored to his dominions, Charles redirected his power southwards against the Swiss Confederacy.

The Swiss Confederacy was an anomaly in medieval Europe. Emerging in the 14th century, the Swiss Confederacy was an amalgamation of rural and urban cantons that held the status of ‘imperial immediacy’ by decree of the Holy Roman Emperor. The Swiss Confederacy grew rapidly between 1307 and 1470, defeating the armies of Habsburg Austria and expanding outwards from the Alps to the Rhine River and the Jura Mountains. By the mid-1460s, the Swiss Confederacy included the cantons of Schwyz, Unterwalden, Uri, Glarus, Zug, Zürich, Luzern, and Bern. Though small in geographic size, the Swiss Confederacy held an invaluable export to the rising nation states of late-medieval Europe: mercenaries. Already feared and admired across Europe, the Swiss mercenaries (Reisläufer) were renowned for their martial valor, in addition to their expertise with the spear, the long pike, and the halberd. The Swiss cantons contracted out their mercenaries to foreign powers while simultaneously maintaining their own local militias, thereby ensuring a policy of defensive neutrality.

The Swiss had kept a watchful eye on the actions and trespasses of Duke Charles; France was their traditional ally against Austria and the employer of thousands of Swiss mercenary soldiers. Swiss soldiers returning to Switzerland from France in the 1460s and 1470s spread tales of extreme barbarism and brutality committed by the Burgundian armies in France after the negation of the Treaty of Péronne (1468). The pro-French Swiss patricians in Zürich, Bern, and Luzern understood well that Charles’ cruelty and malevolence extended to his own subjects and that it would likely extend to them if Charles had his way. They understood that their defeat would ensure Charles’ primacy over Savoy and his ability to isolate France. In turn, Swiss merchants feared Burgundian interference in their trade routes. Acting out of exigency, the Swiss Confederacy made a strategic alliance with the Duchy of Lorraine – whose location split Burgundy in half – hoping that the partnership would buy them time to prepare for a war. The Swiss thus surreptitiously lent aid to the rebellious Archbishopric of Cologne and mercenary soldiers to the beleaguered René II, Duke of Lorraine between 1472 and 1474. As Burgundy was an ally of the duchy of Savoy and Milan – sworn enemies of the Swiss Confederacy – and the Swiss anticipated that an attack directed by Burgundy would be fought on two fronts given their northern border with Burgundy and their southern borders with Savoy and Milan, differences with Austria would need to be set aside for the time being.

Swiss and Austrian diplomats negotiated a treaty of alliance in Konstanz with the support of Sigismund, Archduke of Austria in 1474. Louis XI gave his support and blessing to the alliance as well, and the Swiss Confederacy declared war on Burgundy on October 29, 1474. The Swiss with their Lorrainer allies struck first and attacked the Burgundians at the Battle of Héricourt in November 1474, securing a small victory. The battle was one of the first in European history to have had soldiers fight with handheld guns, but they likely made little difference to its outcome. Charles was not present during the battle – he was fighting at the Siege of Neuss in Germany – but he was enraged to learn that the Swiss had emerged victorious. Adding insult to injury, the Swiss easily routed Charles’ Savoyard ally, Jacques of Savoy, Count of Romont, in the Savoyard-held Vaud and Valais regions. This denied Charles fresh mercenaries from Italy. News from Milan that Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza had repudiated his treaty of alliance and refused to send Milanese troops against the Swiss served only to disillusion Charles’ forces and advisors further. Despite what seemed like an untenable situation, Charles decided not to retreat back to the Low Countries for the winter. In response to Swiss aggression and military success, Charles moved his armies south from Germany to occupy several key castles and towns along Lake Neuchâtel, in order to strengthen his position vis-à-vis the Swiss in Canton Bern. Charles still believed that he needed to defeat the Swiss in order to prevent them from allying with France. After their defeat, Charles could move against the French, who would be bereft of allies.

From the forest

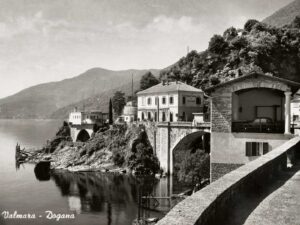

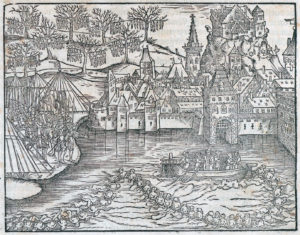

After a brief siege of nine days, Grandson Castle fell to the Burgundians on February 28, 1476. The Swiss garrison at Grandson could not hold out against Charles' large mercenary army and heavy cannons in winter, but they suspected that reinforcements would soon arrive from Bern. A boat had attempted to approach the garrison with news that an army was coming to relieve the siege, but the garrison misunderstood their signalling and gestures. Playing for time, the garrison surrendered to Charles on the condition that their lives would be spared. Charles agreed, but then ordered the entire garrison – 412 men – duly hanged or drowned the lake. Charles believed that Swiss reinforcements would be sent instead to engage the Savoyards in the Vaud, but if they did try to engage the Burgundians, they would have to traverse an old Roman road that ran parallel to the lake. His Burgundian scouts seemed to confirm his suspicions, and Charles felt confident in his strategic position. Indeed, a Swiss army was on its way to Grandson, but unbeknownst to Charles, and they tricked the Burgundians into thinking that they would engage them along the shore of Lake Neuchâtel.

The Swiss reinforcements laid siege to and easily took the nearby castle of Vaumarcus, located further up Lake Neuchâtel, in order to draw the Burgundians away from their strategic positions in and around Grandson Castle. The Swiss army, which consisted of 20,000 men, then moved through the forests of the Jura Mountains to meet the Burgundians outside the town of Concise. In typical fashion, the Swiss advanced in three heavy columns on the morning of March 2, 1476. The Burgundian forces consisted of Flemish and French gendarmes, pikemen, Italian crossbowmen, English longbowmen, and German gunners. They held a tactical advantage by virtue of their numbers and artillery. The Swiss forces were mostly pikemen and halberdiers, with smaller numbers of crossbowmen and gunners. The Burgundian knights and soldiers quickly surrounded the thin Swiss vanguard, but Charles ordered his cavalry to pull back so that he could utilize his artillery weaponry against the Swiss from an opportune location: a snowy plain northeast of Concise. Charles believed that the battle would be short and that the small Swiss force would be promptly defeated. What the Burgundians had not gathered from their own reconnaissance was that the main body of the Swiss army was hidden in the forest, waiting to attack the Burgundian cavalry. The rapid arrival of the Swiss soldiers onto the field of battle caused a wave of panic on the part of the Burgundian army. Withdrawing from the field, the Burgundian forces were ultimately routed by the Swiss as Charles frantically ordered them to stop and return to the engagement. The short battle was over in roughly three hours and each side lost about 300-400 men.

The ‘Burgundian booty’

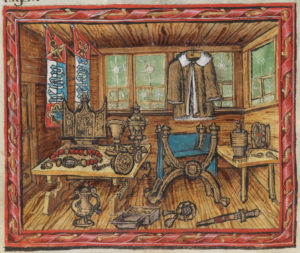

In its immediate aftermath, Swiss forces came into possession of a rich treasure that has since become a legend in its own right. While the 400 pieces of artillery would prove useful against the Burgundians in the subsequent battles of Murten and Nancy, the Swiss were far more delighted with the silverware, religious reliquaries, and even sumptuous clothes and jewellery that now came into their possession. The amount of treasure was so fantastic that the highly disciplined Swiss soldiers even rioted over control of its distribution. Unfortunately for historians, the soldiers melted down or cut up the majority of the Burgundian treasures as a result of contested ownership. A few of the surviving artifacts from the ‘Burgundian booty’ are now dispersed throughout Switzerland, but the National Museum in Zürich contains three fine examples that attest to the wealth and sophistication of Charles’ military entourage. Perhaps the most striking object in the Swiss National Museum's depository is an archer's shield, replete with a painted cross of St. Andrew and fire steels. Made of beechwood, it dates to c.1450–1475 and was likely made from ceremonial robes belonging to nobles who fought with Charles at Grandson and belonged to the Benedictine abbey at Rheinau.

Grandson, like the subsequent battles of Murten (1476) and Nancy (1477), was of great consequence in European history. Burgundy was destroyed as a political power with Charles’ death at Nancy; it would never play a major role in Europe again. France and Austria – and then Germany in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – would now compete over the vast and disparate Burgundian territorial possessions for nearly five centuries.

This article was first published in “Medieval Warfare” IX-6.