When industry meets arts and crafts…

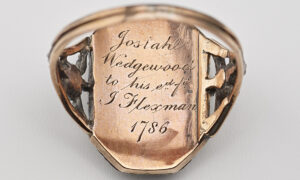

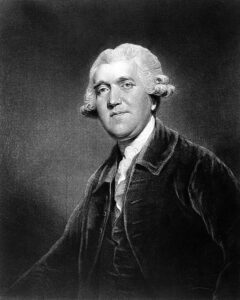

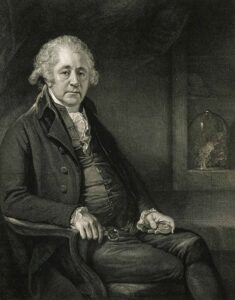

It's amazing what a finger ring can tell you. For example, the life story of Josiah Wedgwood, who elevated pottery to an art form in the 18th century and did not shy away from industrialisation.

The collection

The exhibition showcases more than 7,000 exhibits from the Museum’s own collection, highlighting Swiss artistry and craftsmanship over a period of about 1,000 years. The exhibition spaces themselves are important witnesses to contemporary history, and tie in with the objects displayed to create a historically dense atmosphere that allows visitors to immerse themselves deeply in the past.