The Shah’s Swiss watchmaker

Zurich watchmaker Rudolf Stadler came to a bloody end on 16 October 1637. At the age of 32, the first Court watchmaker to the Shah of Persia in Isfahan was executed by sword. His story sounds like a tale from One Thousand and One Nights.

Rudolf Stadler’s origins

Stadler met a bloody end

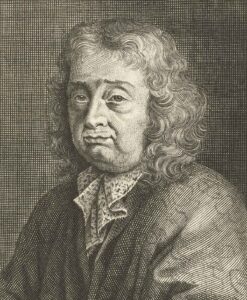

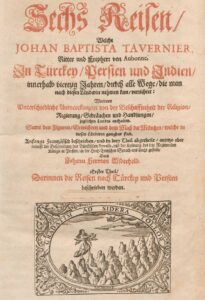

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier and Vaud

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier had an obvious weakness for Vaud. In his notes on the journey from Constantinople to Isfahan, on which he was accompanied by Stadler, he compared the region around Yerevan to Vaud: “I cannot compare this mountainous tract, whether for its valleys or rivers, or for the nature of the soil, to anywhere that I have seen, better than to that portion of Switzerland called the Pays de Vaud; and it is said by the natives that certain people who lived between the Alps and the Jura, and who composed a squadron of Alexander’s Army, having served him in his conquests, settled in this part of Armenia and made it look like their own country” (cited from ‘The six voyages of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier... to Turkey, Persia and India over forty years’ which was published by Johann Hermann Widerhold in Geneva in 1681). In 1670, Tavernier finally acquired the Aubonne Barony and had the castle renovated and converted. In the process, the original rectangular tower was given its distinctive appearance, reminiscent of an oriental minaret with a Russian domed roof, marking it out as a local landmark in Aubonne.