NATEL – from status symbol to everyday object

In 1978, PTT launched the National Car Telephone, or Natel for short. For the first time ever, Switzerland could make mobile calls using a telephone inside a briefcase, heralding the start of mobile telephony’s meteoric rise. By the turn of the millennium, it had gone from being a status symbol in Switzerland to an everyday object which everyone takes for granted.

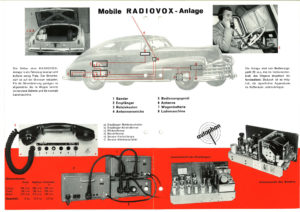

The history of mobile telephony began out of the limelight during the post-war era at Autophon AG in Solothurn. This company took police radios and developed them into the country’s first mobile telephone device. The system was called “Radiovox”, and it took up half the boot space in a car. As the word “Radio” in the brand name suggests, wireless technology was used for the system. Zurich transport company Welti-Furrer began using the first Radiovox system on 9 June 1949, which meant that it could then reach its fleet of vehicles by telephone. Three years later, a world first was even launched in Switzerland: the first system that allowed automatic dialling between a vehicle and a stationary telephone subscriber. Vehicles belonging to Zurich industrial enterprises and the Lake Zurich motor vessel “Linth” were the first to be connected, followed by other taxi and transport companies. However, the reach of these “mobile phones” was not great – they only worked within a radius of 25 kilometres from a fixed transmitting and receiving station. By 1975, 62 independent networks had been generated in Switzerland with an impressive 1,300 subscribers in total.

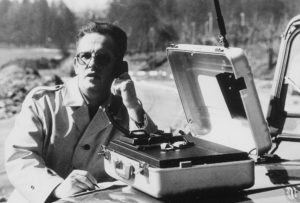

In 1978, the devices received a second boost to their mobility, becoming portable. PTT, in collaboration with Autophon AG, Brown Boveri & Cie and Standard Telefon und Radio AG, launched Natel A, the National Car Telephone, the first Swiss-wide mobile phone system. This meant that, alongside fixed models installed inside the vehicle, subscribers could now obtain Natel phones housed in portable briefcases – albeit weighing a hefty 15 kilograms. So, still nothing like the mobile phones we have today. Depending on the model, a Natel A cost between 8,000 and 10,000 Swiss francs, which is equivalent to around 20,000 francs today when considered in terms of spending power. Added to that was a monthly basic charge of 130 francs. A three-minute call involved shelling out 5 Swiss francs. PTT worked out for potential customers that the mobile phone costs for one working day would total 11 to 16 francs and promised, at the same time, savings in vehicle trips and staff. Obviously, the high costs meant that car telephones soon became a status symbol. In Zurich, the demand was so great that a number of requests for a Natel A were turned down. One rejected customer in 1979 bitterly complained in a letter that many Natel users were merely using the device as a status symbol and barely made any business-related phone calls in evening rush-hour traffic jams.

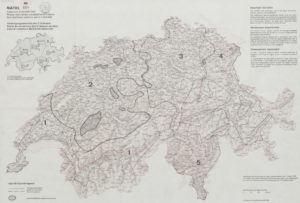

The Natel A system was essentially a small analogue radio system. The Natel A automatically dialled into the telephone network by radio at the next radio antenna. At this time, Switzerland was divided into five network supply areas, each with its own area code. So, to reach someone you also had to know which area of Switzerland that person was in at that particular time for a mobile conversation. In fact, everything was rather complicated during this pioneering era. It could take up to two minutes to establish a connection. And once the call was connected time was of the essence. After three minutes the call would automatically be disconnected for fear of overloading the network. Anyone who used a Natel A to make a call had to be quick and to the point. The Natel A was no good for chatting.

The Natel subnetworks in Switzerland. To reach someone the caller had to know which area that person was in at that particular time for a mobile conversation. Illustration: PTT-Archiv, Köniz

Dead spots in mountainous areas or in street canyons were all too common back then. This led to complaints. “It is no secret that the Natel car telephone systems are far from satisfactory. Unfortunately, I have today realised that the cost of CHF 11,000 per device plus the call-signalling charges were a complete waste of money,” wrote one dissatisfied customer to PTT a few months after the network was opened.

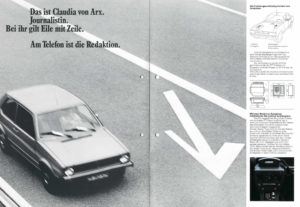

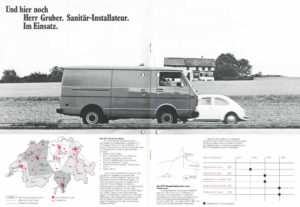

The early advertisements therefore targeted business customers who travelled a lot for work and had very little time: managers, tradesmen and SME owners. Advertising was usually aimed directly at men. Though, one motif with a loose rhyme was addressed at the modern woman. She drove a VW Golf: “This is Claudia von Arx. A journalist. She’s always rushing about to get a story out.” Naturally, Claudia von Arx is behind the wheel talking on the phone. This was a popular motif in advertising as it was not prohibited in the early days of the Natel. Though, as far back as 1979, PTT recommended that subscribers pay full attention to the road and not talk on the phone while driving. However, administrative fines for using a phone without a hands-free device while driving did not exist until 1996. Prior to this, the police had to file criminal charges. Finally, in 2009, the Federal Court also categorised writing an SMS as a serious traffic violation – punishable with imprisonment of up to three years or a hefty fine.

People happily used the Natel A even while driving. Nowadays, this is prohibited without a hands-free kit. Autophon brochure from 1978. Illustration: Museum of Communication, Berne

The Natel A was later replaced by the likewise analogue systems Natel B and C. The various systems co-existed for some time. In 1992, the digital Natel D was launched. This was based on the European GSM system. The devices quickly became smaller, cheaper and, from then on, the majority were no longer made in Switzerland. The lower prices for the devices and subscriptions enabled mobile telephony to catch on in everyday life. The introduction of SMS technology from 1995 onwards also contributed to its success. The 160 characters of the short message increasingly replaced a mobile phone conversation. This also impacted on fixed-line telephony from the turn of the millennium. In 2002, the statistics for Switzerland counted more mobile connections than fixed-line ones for the first time. What is more, from 2007 there were more mobile phone subscriptions than inhabitants. In the same year, Apple launched the iPhone, starting the trend away from keys in the direction of smartphones with touchscreens. The mobile phone well and truly became a multifunctional device thanks to individually selectable apps. Telephone, internet browser, connection to social networks, walkman, timetable, camera, diary, torch and compass all now fitted in your pocket inside one device.

But one thing remained the same for a long time: the device was called Natel. A term that was understood and used in all four national languages. Following the end of PTT’s mobile communications monopoly, Swisscom even trademarked the word in 1999. However, in 2017, the same company decided to stop using the word Natel for its mobile tariffs. It remains to be seen how long this Swissism will continue to be used by the general public…