Swiss National Museum / ASL

Text and a picture, to hold it all together!

Text or picture? Which is more important? It’s still a matter of debate. A look back at the past shows these two forms of communication work hand in glove.

A picture is worth a thousand words. When American advertising executive Fred Barnard first put that sentence to paper in the early 20th century, he could have had no idea what he was creating. The neat little saying is still widely used today. All Barnard was trying to do was boost advertising by putting pictures on trams. The American later revealed he had pulled a bit of a fast one, admitting he had lied about the slogan being a Chinese proverb.

For decades, it’s been a topic of debate in marketing, and particularly in journalism: which is more important – image or text? You could spend days philosophising on this question but essentially, it’s fair to say that it takes both to fully convey information. A picture without a caption can be difficult to understand, and text without an image is just a ‘desert of ink’. However, it’s not just in highly charged political reportage, or an interview with a starlet, that the interplay of image and word is important. Even in respect of everyday topics, photographs and text should work to complement each other.

Saviez-vous? Ivory chains should be cleaned using milk and a paintbrush. Handy housekeeping tip from the magazine Lectures du Foyer, 1940s.

Swiss National Museum / ASL

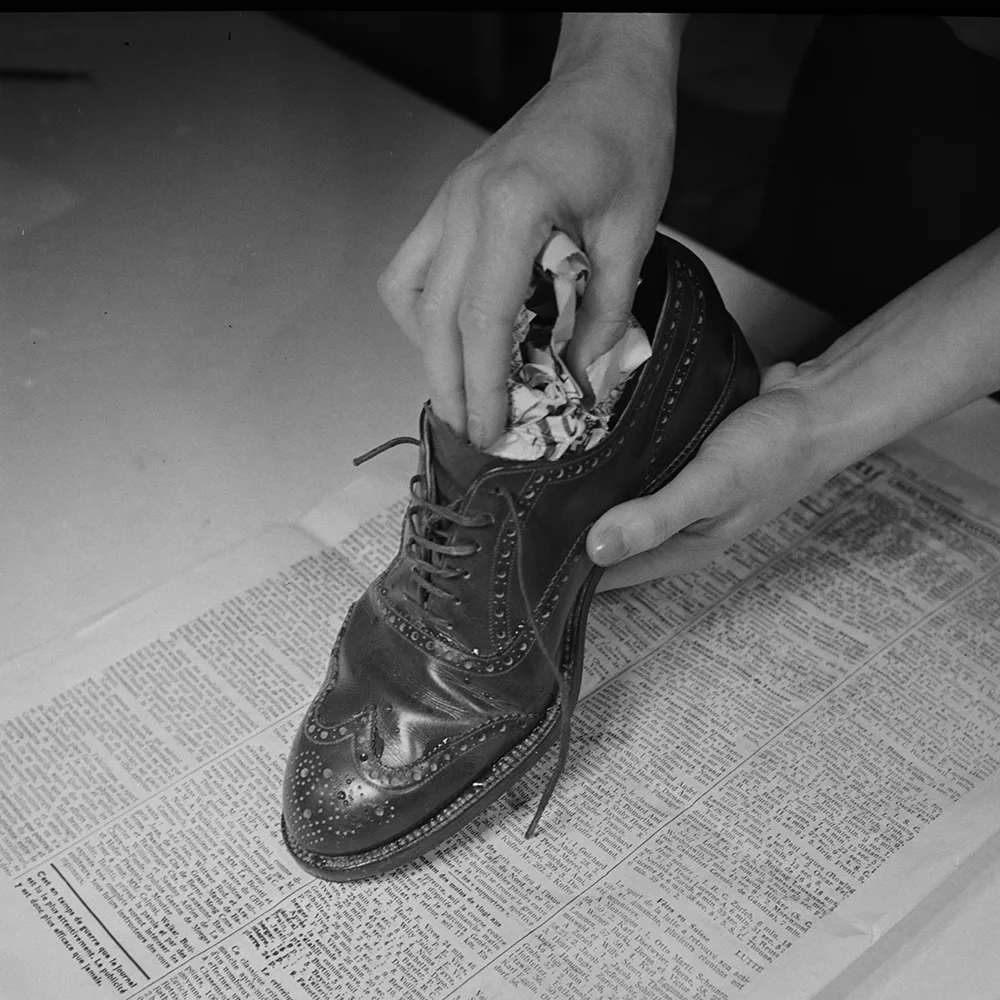

Saviez-vous? Stuff wet shoes with newspaper. Handy housekeeping tip from the magazine Lectures du Foyer, 1940s.

Swiss National Museum / ASL

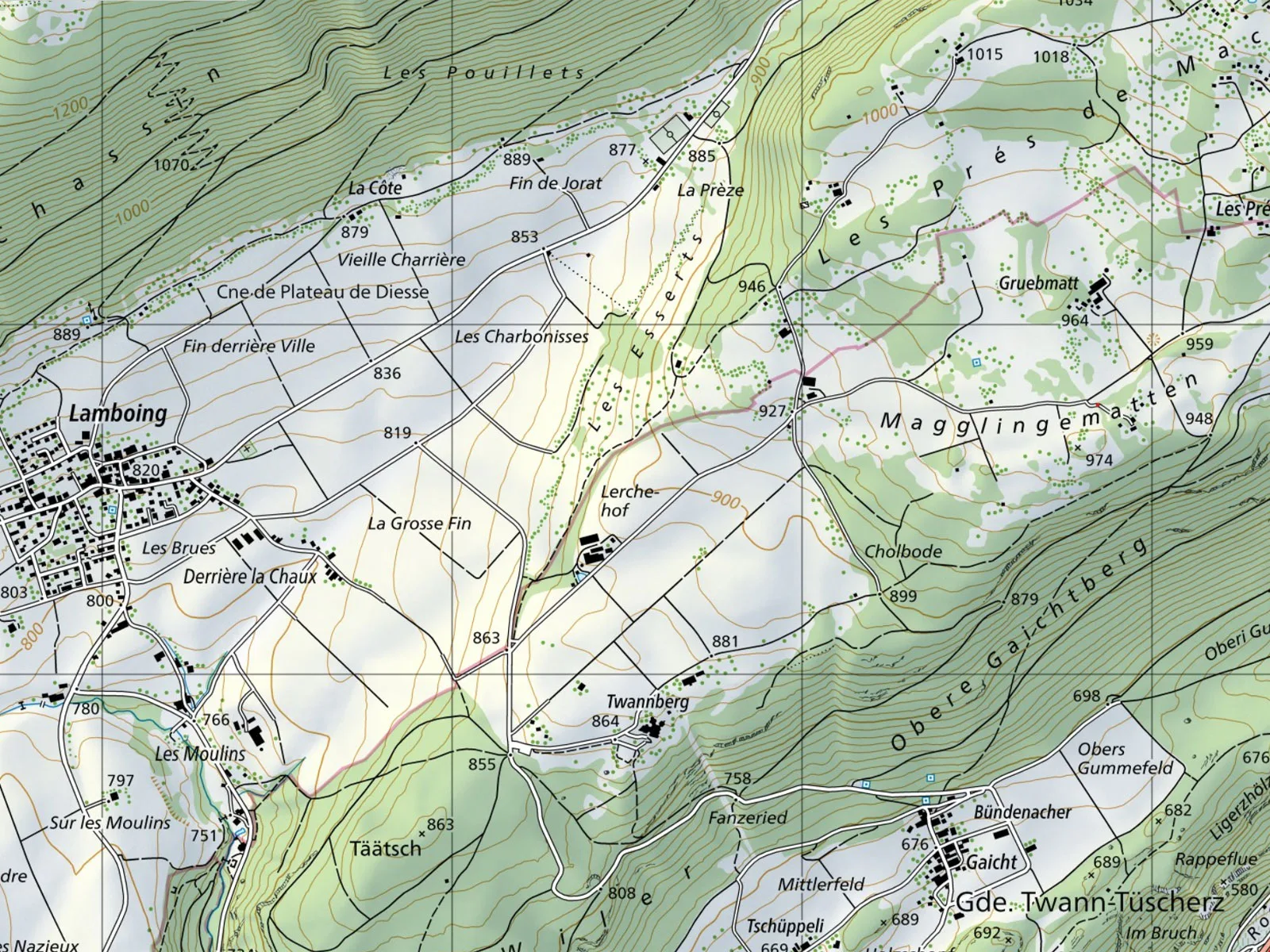

A good example of this is a series published in the 1940s in the glossy magazine Lectures du Foyer. Under the heading ‘Saviez-vous?’, the magazine regularly gave out handy housekeeping tips using pictures and text. The advice and instructions were popular, and were an established part of the content in other magazines as well. Lectures du Foyer was published by Zurich publishing house Conzett & Huber. Subscribers to the magazine not only received regular reading material, but were also insured against accidents. This business model originally came from the UK, making its way to Switzerland via Germany.

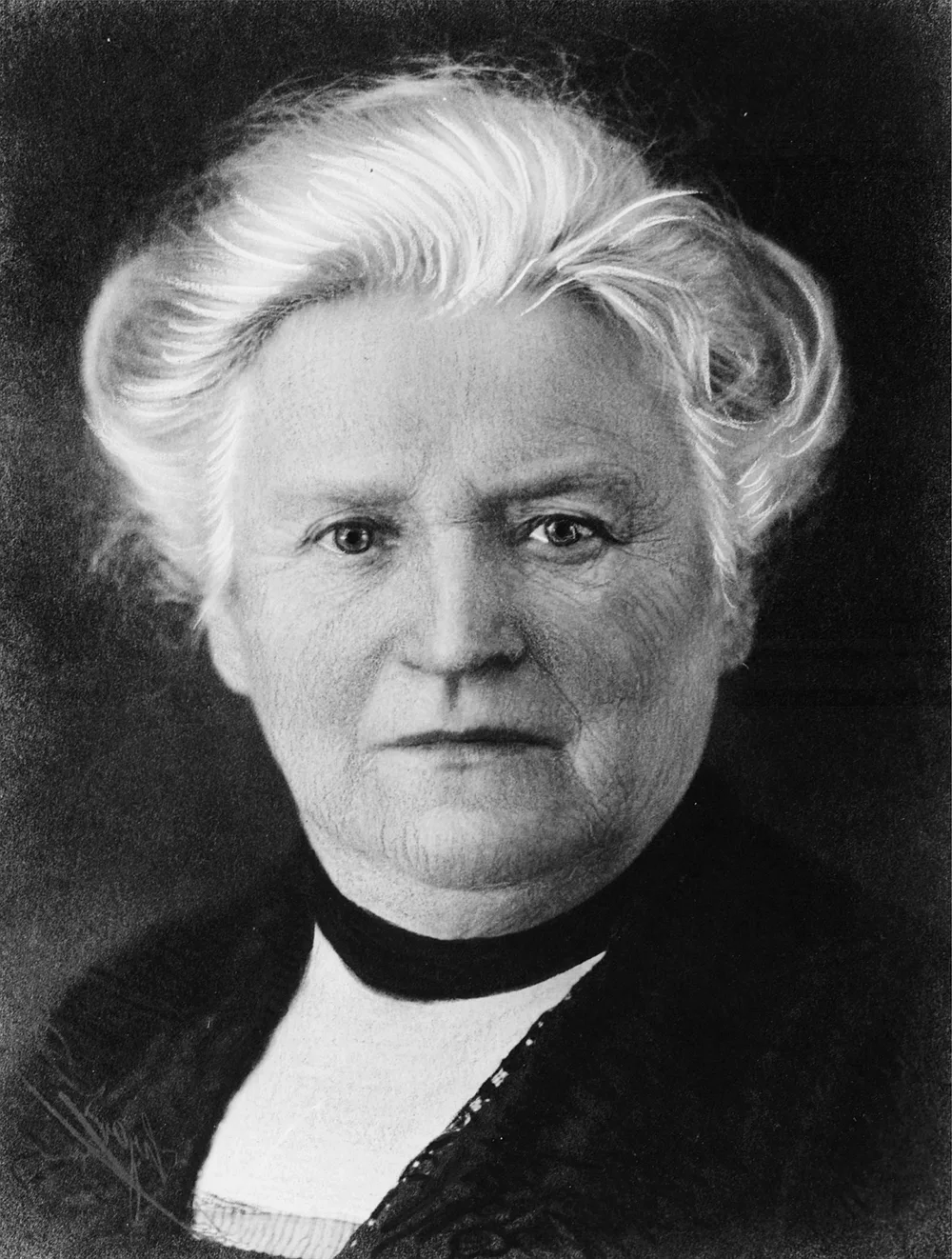

Behind the company, which later also went on to publish the prestigious cultural magazine ‘DU’, was Zurich women’s rights activist Verena Conzett-Knecht. She believed combining insurance cover and a magazine was important, because at the beginning of the 20th century mandatory medical and accident insurance didn’t yet exist in Switzerland. It was only agreed to by Swiss voters in 1912. But there were also economic reasons for combining entertainment and insurance coverage in a single product. Bringing the two together was a means to acquire customers and retain customer loyalty.

Were the handy housekeeping tips perhaps a ‘covert’ prevention campaign to cut down accidents in the home and thus reduce the costs of insurance payments? We can’t be sure. What is certain, however, is that Verena Conzett-Knecht and other publishers quickly realised the information would best be taken on board by readers if it was conveyed by mutually complementary forms of communication.

Portrait of Verena Conzett-Knecht, about 1930.

Wikimedia