A brief history of e‑mobility

For decades electrically powered vehicles were considered exotic, but today everyone’s talking about them. What is less well known is that 120 years ago, electric vehicles were all the rage. In those days, around half of all engine-driven vehicles in New York were electric vehicles. Switzerland’s contributions to e-mobility have been recognised worldwide.

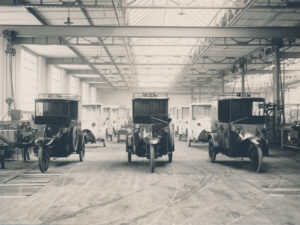

Electric vehicle pioneer Johann Albert Tribelhorn

The petrol engine drives out the electric

Tour de Sol

From central Switzerland to the moon