Swiss Museum of Transport

All electricity is not the same

At the beginning of the 20th century, the electrification of the SBB was a hugely important step for the fledgling electricity sector. However, the issue of what type of energy should be used was a source of tension.

As elsewhere, the electrification of businesses and households heralded the start of the second industrial revolution in Switzerland. With centralised production and decentralised use, people were quick to embrace the new form of energy. Electric light bulbs turned night into day, while electric motors drove machinery and railway trains – without the foul-smelling clouds of smoke and steam. Up to 1900, the young and innovative electrical industry mainly built power plants and electrified some railway lines. Everything going well? Not quite! What the electricity producers lacked was bulk energy consumers. So in 1902 the sector decided, quite audaciously, to electrify the SBB, Switzerland’s federal railway system, which was founded that same year.

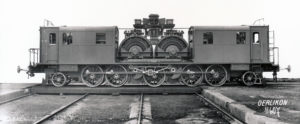

Before this ‘monster project’ could be tackled, however, an internal dispute had to be resolved: single-phase alternating current or three-phase current? From 1905, the company Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon (MFO) had been operating the Zurich Seebach-Wettingen route with single-phase alternating current, while Brown Boveri & Cie. (BBC) supplied the Simplon Tunnel with three-phase current from 1906 onwards. The tensions between MFO and BBC played into the hands of the federal railways (Bundesbahnen), because the national railway company was, for one thing, very busy with developing a national infrastructure, and therefore not necessarily interested in rapid implementation of this latest innovation. Secondly, the dispute meant it was able to simply wait and see which of the electricity systems would win the day.

On the Zurich Seebach-Wettingen test track, MFO used the Ce 4/4 II locomotive to test electrical operation with single-phase alternating current.

Swiss Museum of Transport

DECISION ON THE GOTTHARD

The years passed, the rail network grew, but the electricity issue remained unresolved. It wasn’t until 1912 that things started to move. The Swiss Study Commission for Electric Railway Operation (Schweizerische Studienkommission für elektrischen Bahnbetrieb) recommended the single-phase alternating current that is still used today. The BLS started operating just a year later. The issue of the type of electricity used in Swiss rail transportation seemed to have been settled. Seemed, because with the outbreak of World War I the SBB suspended its planning works.

For Walter Boveri (1865-1924), co-founder of the BBC and a member of the SBB’s management board, the hiatus came at just the right time. He made use of the time and pulled some strings, so that in 1916 the SBB was planning a trial with direct current at the Gotthard, because three-phase current had not proved successful. This brought the single-phase alternating current faction out of its lair. This time, their argument focused not only on the price and the greater efficiency of electric operation, but also on the more secure operation with domestic energy and the greater value creation for the country. This argument hit the mark, because the scarcity and the high price of coal had made Switzerland acutely aware of its dependence on other countries. The price of coal had increased tenfold from 1914 to 1920.

It was clear to everyone that the decision on the Gotthard would point the way for the whole rail network, so there was no expectation of an amicable agreement. And this expectation was confirmed in 1916.

The BLS locomotive Be 5/7 dating from 1913 was able to run heavier trains over the Lötschberg much faster than the steam engines of the SBB trains could cover the Gotthard.

Swiss Museum of Transport

On 18 February, the management board of the SBB decided to electrify the Gotthard line using single-phase alternating current. SBB board member Walter Boveri voted against the proposal, and continued to fight for direct current. In July 1916, he wrote to the federal railways management that they would be choosing the wrong system. He implied that the single-phase alternating current faction was opposed to a uniform Swiss electricity system.

Boveri’s attack caused some red faces, but ultimately had no effect. The SBB didn’t allow itself to be swayed any more, and resumed its work on the electrification project. On 12 December 1920, electric trains ran from Erstfeld to Biasca. The federal railway company had decided two years earlier to supply its entire network with single-phase alternating current. This decision was hugely important, and laid the foundation for the development of the Swiss electricity sector. By 1936, more than 70% of the SBB network was electrified. During World War II, thanks in part to electric trains, the railways became part of the legend of an independent Switzerland, linking the Swiss people together.

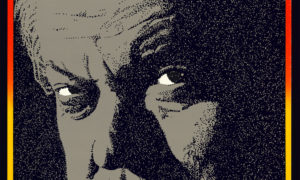

Walter Boveri, co-founder of BBC (Brown Boveri & Cie).

ABB Archive