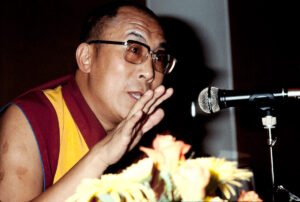

The Dalai Lama’s long journey to Bern

For 60 years, Switzerland has been home to the largest Tibetan community in Europe. But it wasn’t until 1991 that the Dalai Lama was received by the Federal Council for the first time.

The Dalai Lama’s first meeting with a Federal Councillor, 1991 (in German). SRF

Gemeinsame Forschung

This text is the product of a collaboration between the Swiss National Museum and the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland research centre (Dodis). The SNM is researching images relating to Switzerland’s foreign policy in the archives of the agency Actualités Suisses Lausanne (ASL), and Dodis puts these photographs in context using the official source material. The files for 1991 were be made public on the Dodis online database in January 2022. The documents cited in the text are available online: dodis.ch/C2311.