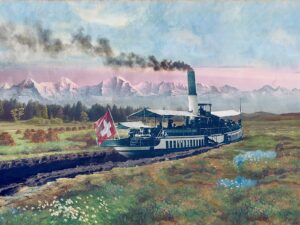

The energy source from the moors

The threat of an energy shortage is nothing new to Switzerland, where demand has repeatedly exceeded supply over the years. However, one energy source that has always proved especially popular in times of crisis is now off limits – peat.