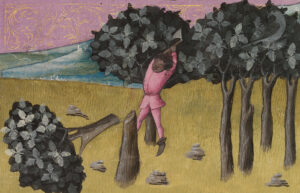

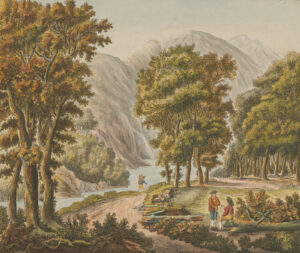

“Rüti” and “Schwand” indicate historical clear-felling of forests

The forests of Switzerland have been managed since time immemorial – and for centuries, they were also cleared on a large scale. The complex relationship between humans and the forest is immortalised in the names of towns and localities.