The dramatic rescue of a composer’s remains

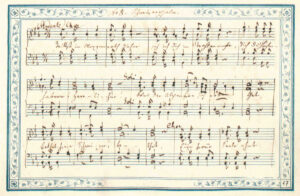

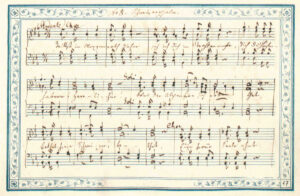

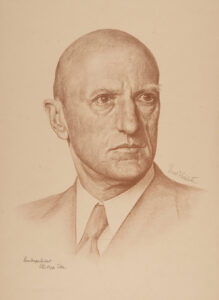

Alberik Zwyssig (1808–1854), the musical monk from Uri who composed the Swiss Psalm, had an unhappy life. And then, after his death, his remains were dug up and reburied during the Second World War.

Alberik Zwyssig (1808–1854), the musical monk from Uri who composed the Swiss Psalm, had an unhappy life. And then, after his death, his remains were dug up and reburied during the Second World War.