Switzerland’s first architect of cultural policy

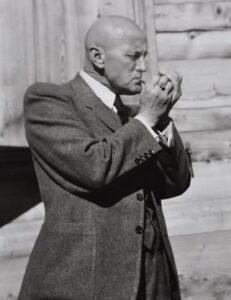

Federal Councillor Philipp Etter held office for 25 years. Laying out Switzerland’s cultural policy from the 1930s onwards was one of his greatest challenges.

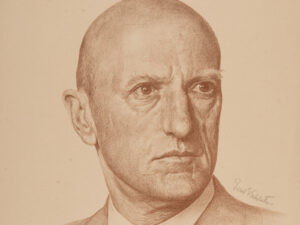

Minister for Culture Philipp Etter

Ambivalent relationship with ‘supporting the arts’

Opinions were divided on Etter’s cultural policy