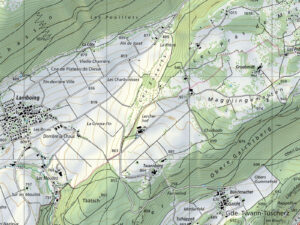

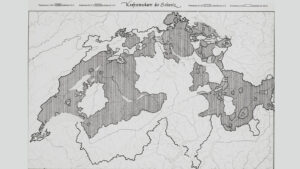

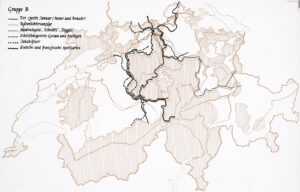

The Brünig-Napf-Reuss line: a cultural boundary through Switzerland

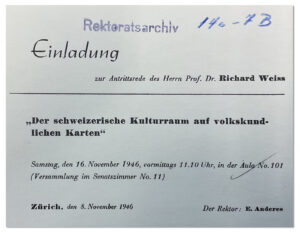

The theory of a cultural divide running through Switzerland first emerged at the time of the “spiritual defence of the nation”, a time when academic research into folklore was being strongly promoted. This cultural boundary, which did not coincide with the language border, was supposed to provide evidence of national identity and cultural diversity.

The theory

The background

The repercussions

Multilingual Switzerland

In Switzerland, you can hear countless dialects, accents, types of slang and immigrant languages in addition to the four national languages. Visit the National Museum Zurich for a sensory journey through Switzerland’s language areas. Find out through interactive sound technology how the predecessors of our languages emerged, evolved or died out, how new linguistic and cultural borders arose and how they were (and still are) disputed.