The sinking of the Lusitania and the fate of its Swiss occupants

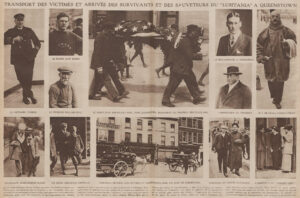

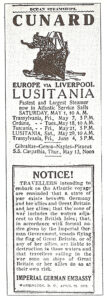

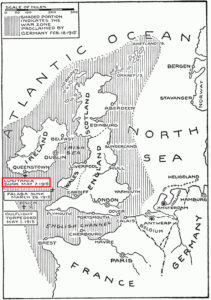

The sinking of the British passenger ship RMS "Lusitania" on 7 May 1915 by a German submarine is one of the worst maritime disasters in recent history. 1193 men, women and children lost their lives off the Irish coast. The stories of the "Lusitania's" Swiss voyagers afford unique perspectives into the Edwardian Age as it came to a conclusion.

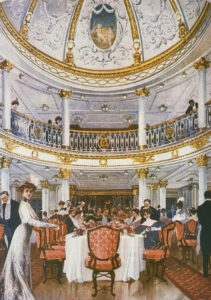

Vignettes of Swiss Lives during the Edwardian Era

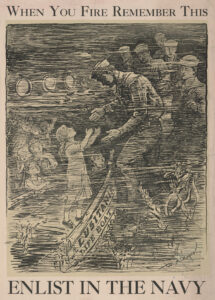

World War One & The Lusitania’s Demise

Lessons from the Lusitania