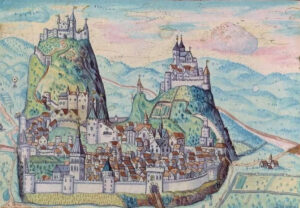

Matthäus Schiner: A Valaisan at the centre of power

From peasant’s son to almost Pope: Matthäus Schiner (c. 1465-1522), who came from the Upper Valais, was a decisive figure in European politics during the height of Swiss power in Europe. He remains controversial to this day.

Schiner’s Formative Years

I want to wash my hands, drinking in the blood of the French.

The Great Game of Power

A rough lump like this Schiner, whose words have hurt me more than all the lances of his mountain people…

Frenetic Final Years

I only wish that what each of us is engaged in may be successful, or rather that what we are all engaged in may tend equally to the glory of Christ.