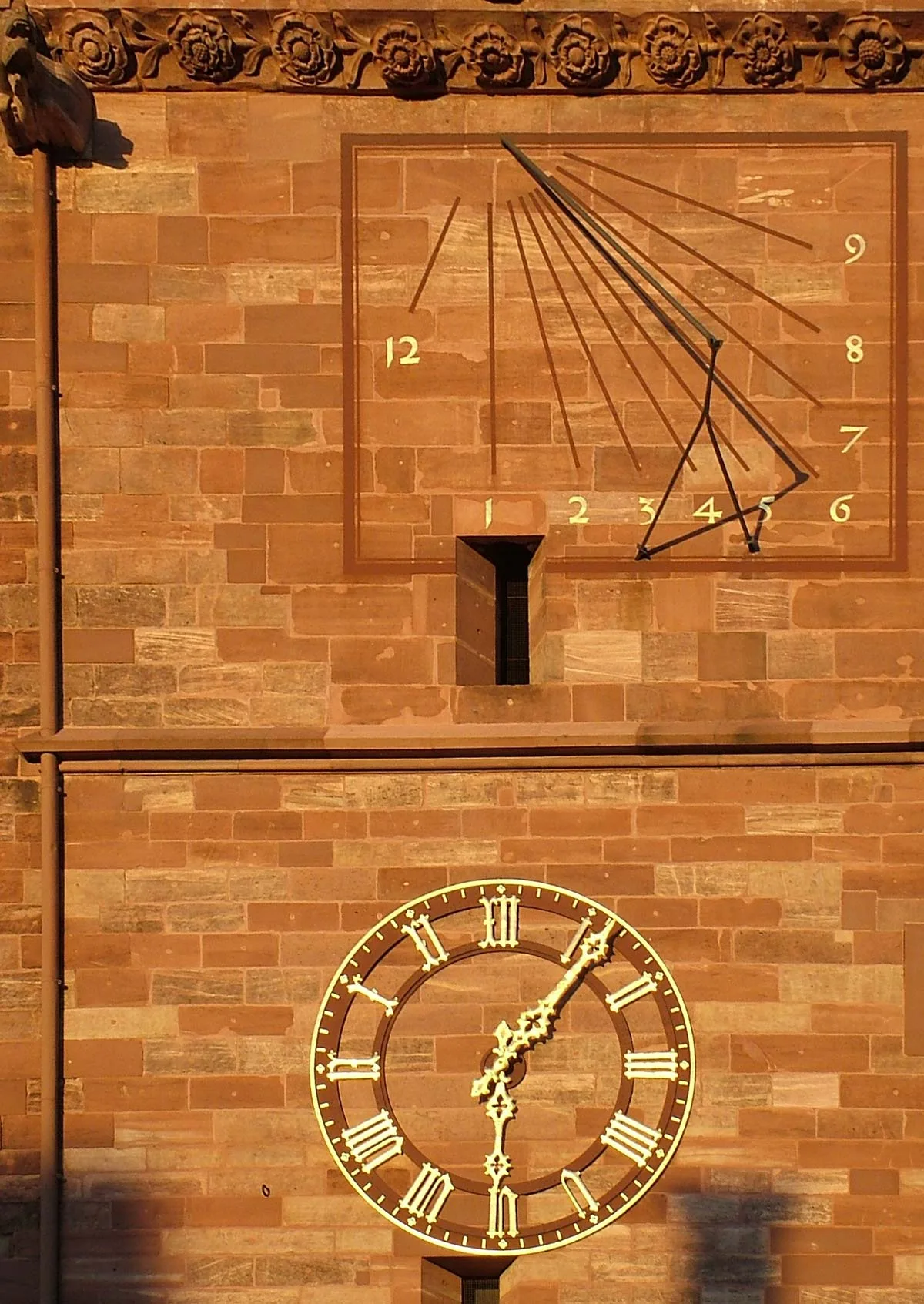

Only count your sunny hours …

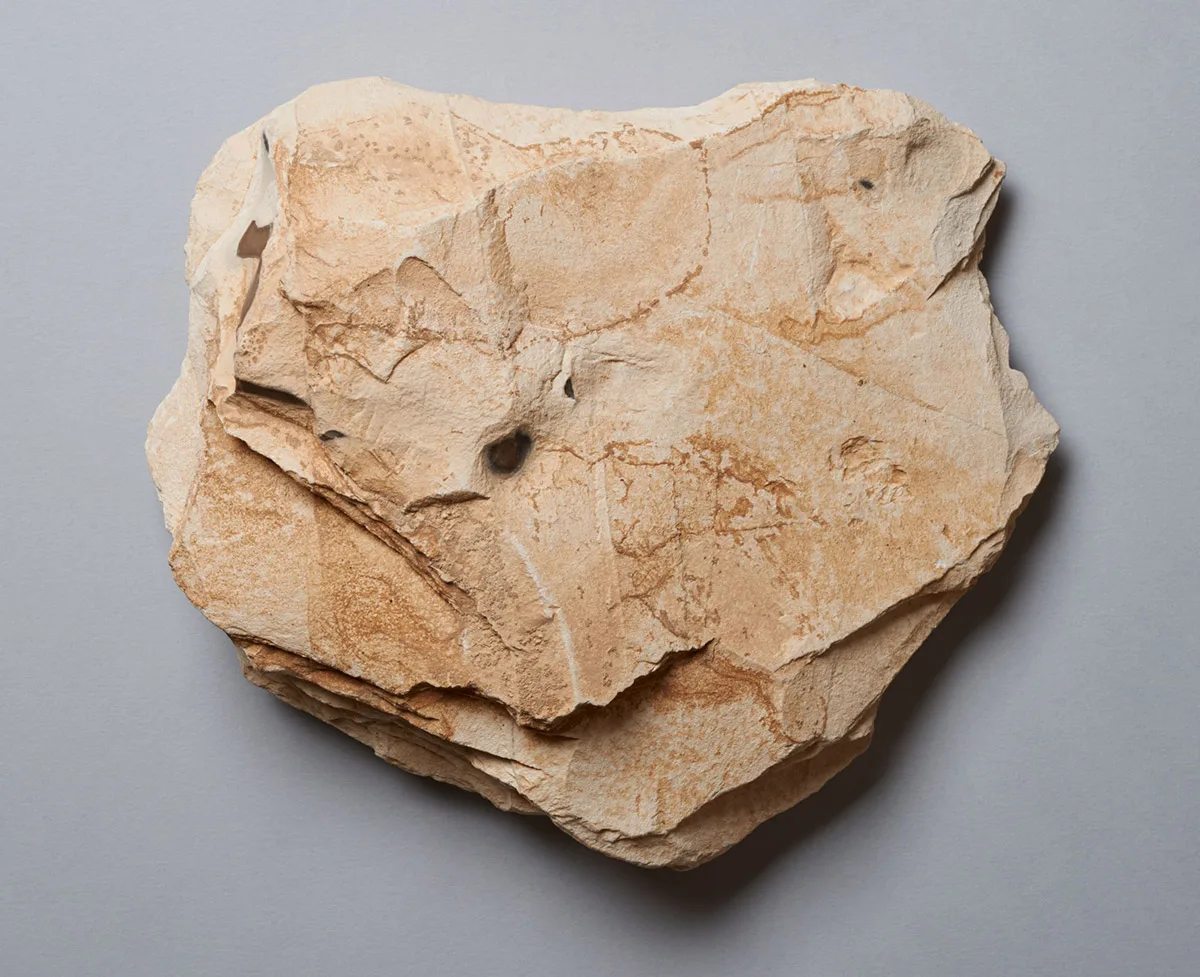

"Let others tell of storms and showers, I’ll only count your sunny hours" is a phrase that has graced countless poetry albums. Researchers from the University of Basel have now found out that the sundial has been in use for at least 3,200 years.

Shorter and longer hours

“Sundial country” Switzerland