The King of Thun and his links with Mycenae

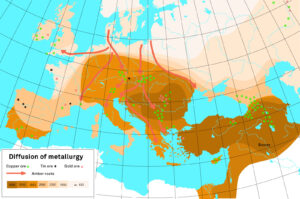

In the early Bronze Age, the area around Lake Thun benefited from its position on important trade routes. Members of the wealthy elite had themselves buried along with magnificent grave goods. These objects indicate connections reaching as far afield as Mycenae, Cyprus, Anatolia and the Gaza Strip.

Trailer for the exhibition "And then came bronze!" at the Bernisches Historisches Museum YouTube/ BHM

And then came bronze!

The “Bronze Hand of Prêles”, found in 2017 in the Bernese Jura, is one of the outstanding testimonies to the Bronze Age in Europe. It is the oldest replica of a human body part in bronze known in Europe, and places the Bernese Seeland on a level with advanced civilizations at that time in Babylon, Crete and Troy.

The exhibition is core to the focus topic for the Bernisches Historisches Museum in 2024, “Bronze”. It is accompanied by a rich variety of supporting events and educational offers.

For further information on the exhibition click here.