George, Martin, Nicholas – timeless humanity

The legends of the saints are written without footnotes. They can’t be checked and verified. The significance of these legends lies in the moral ideal that lives on in elaborate portrayals as a gentle entreaty to follow their saintly example.

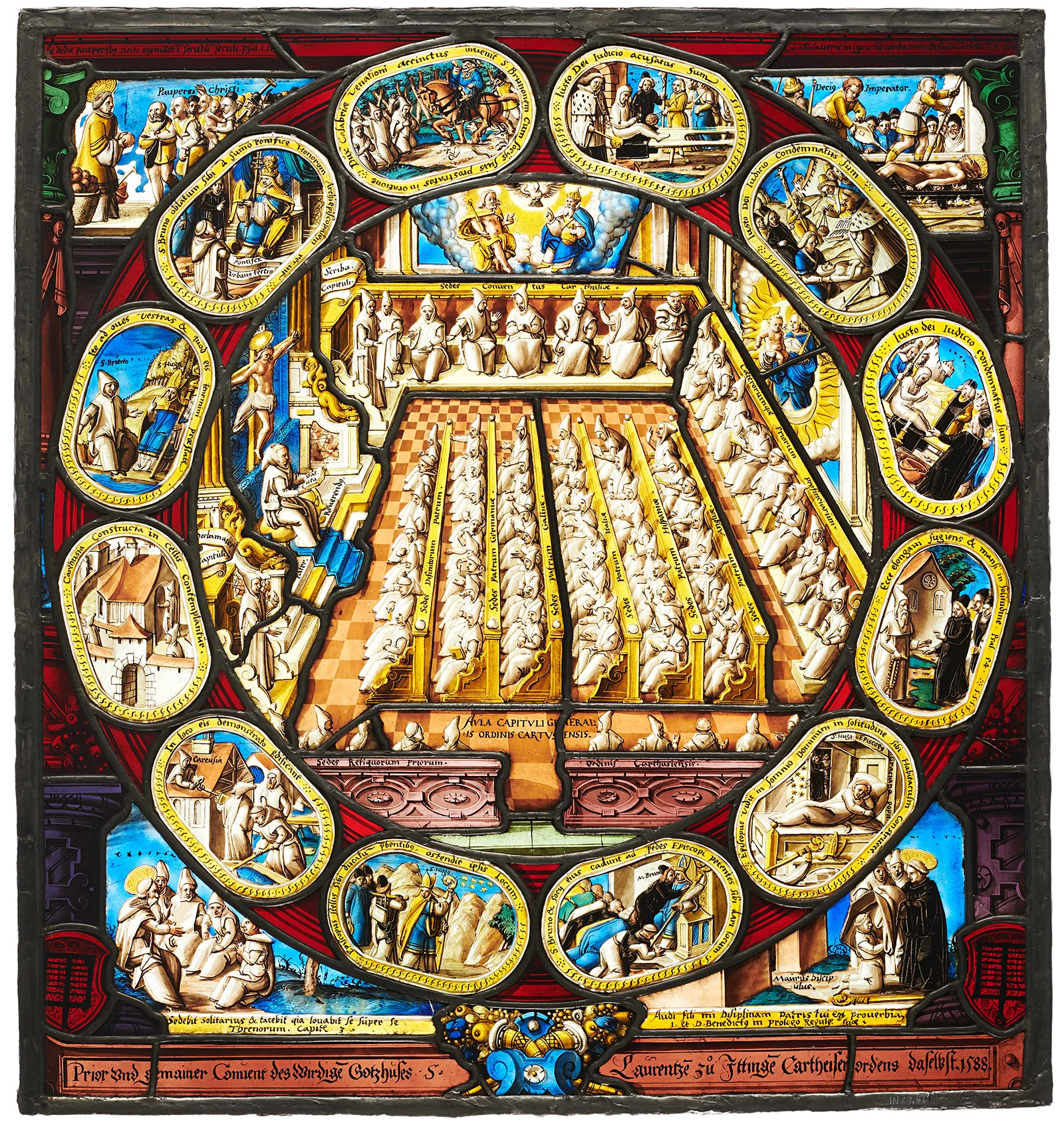

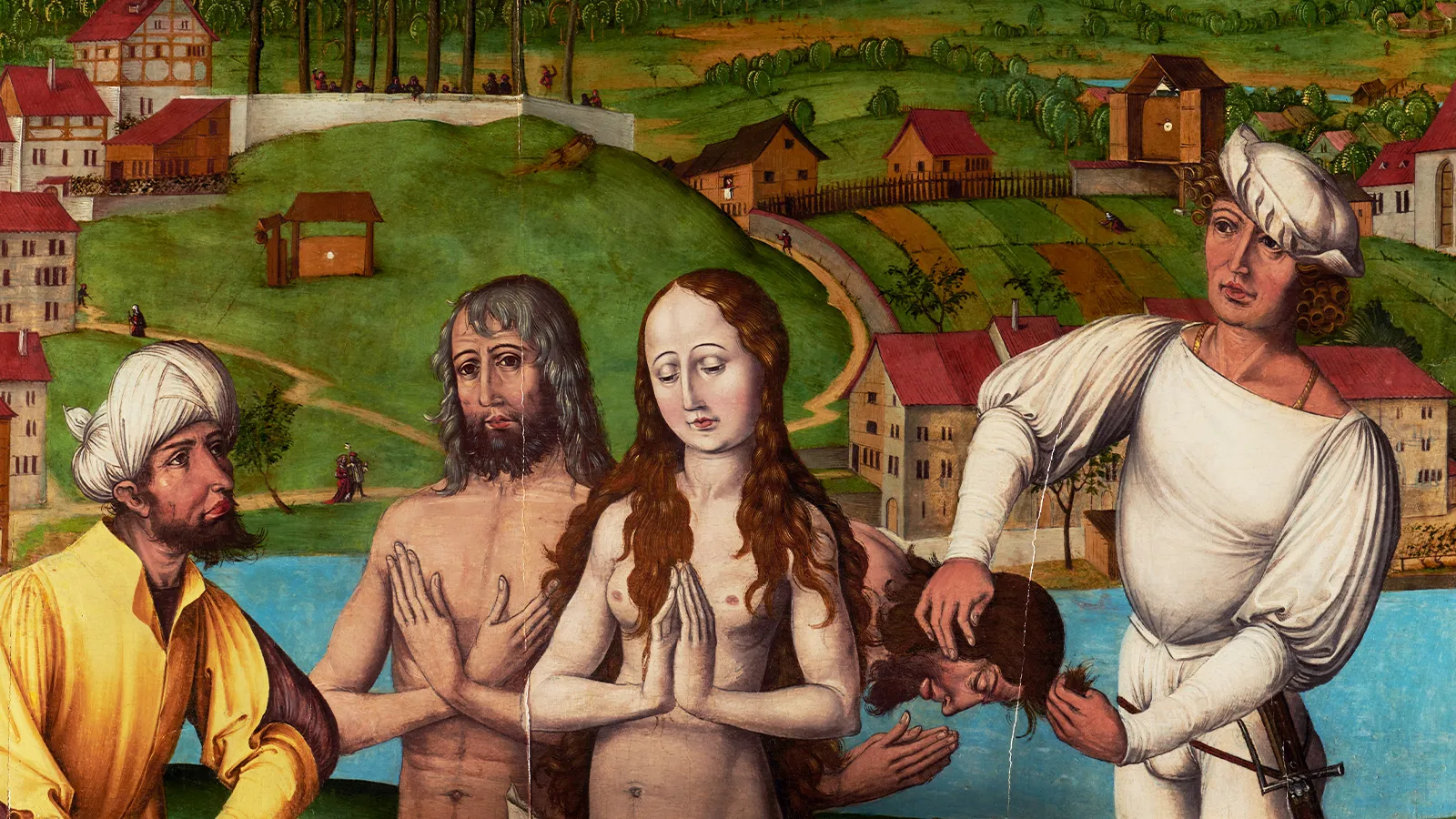

The Fourteen Holy Helpers

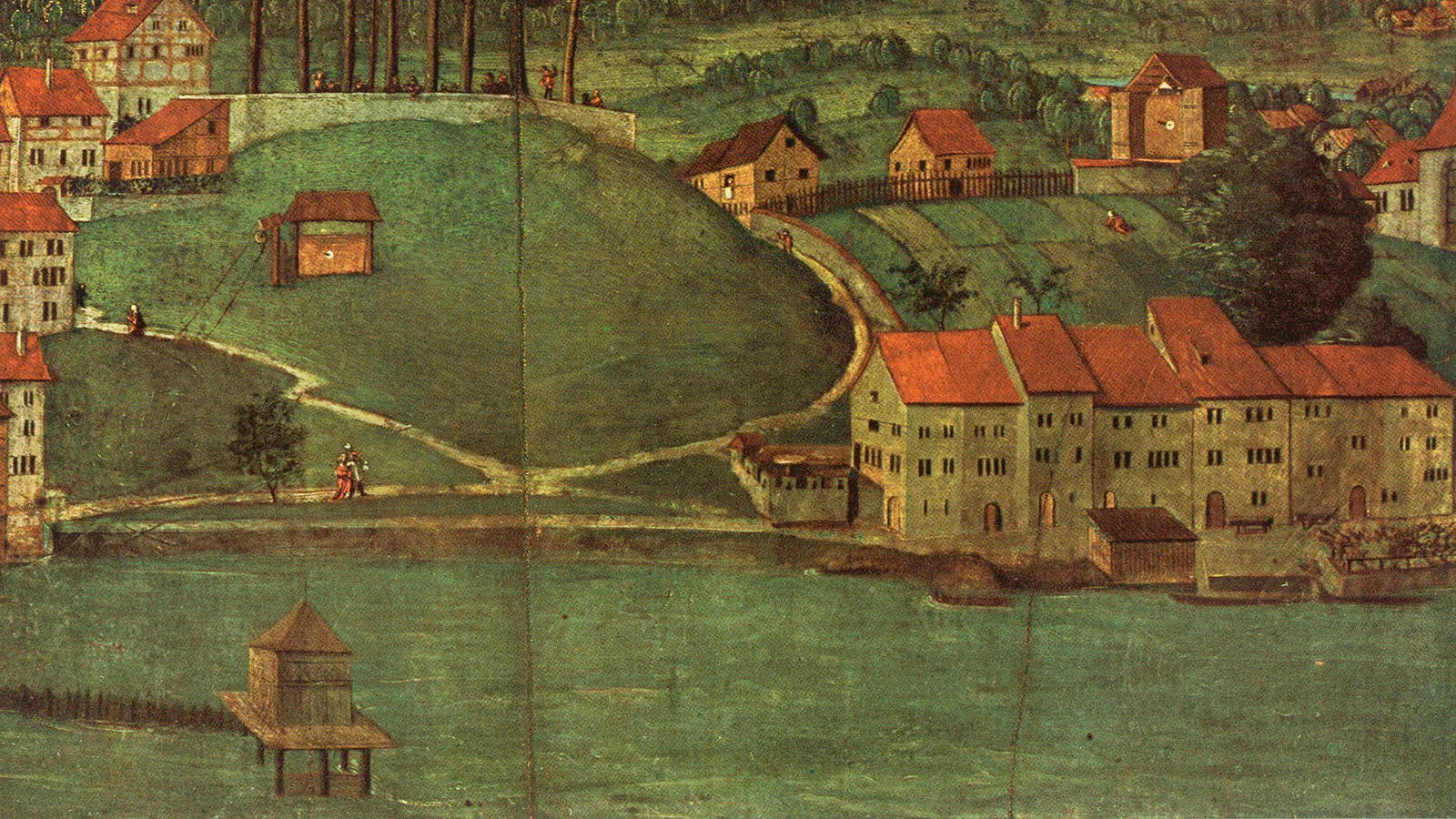

‘John, you must go in the stove!’ – Reformation, banishment of the saints

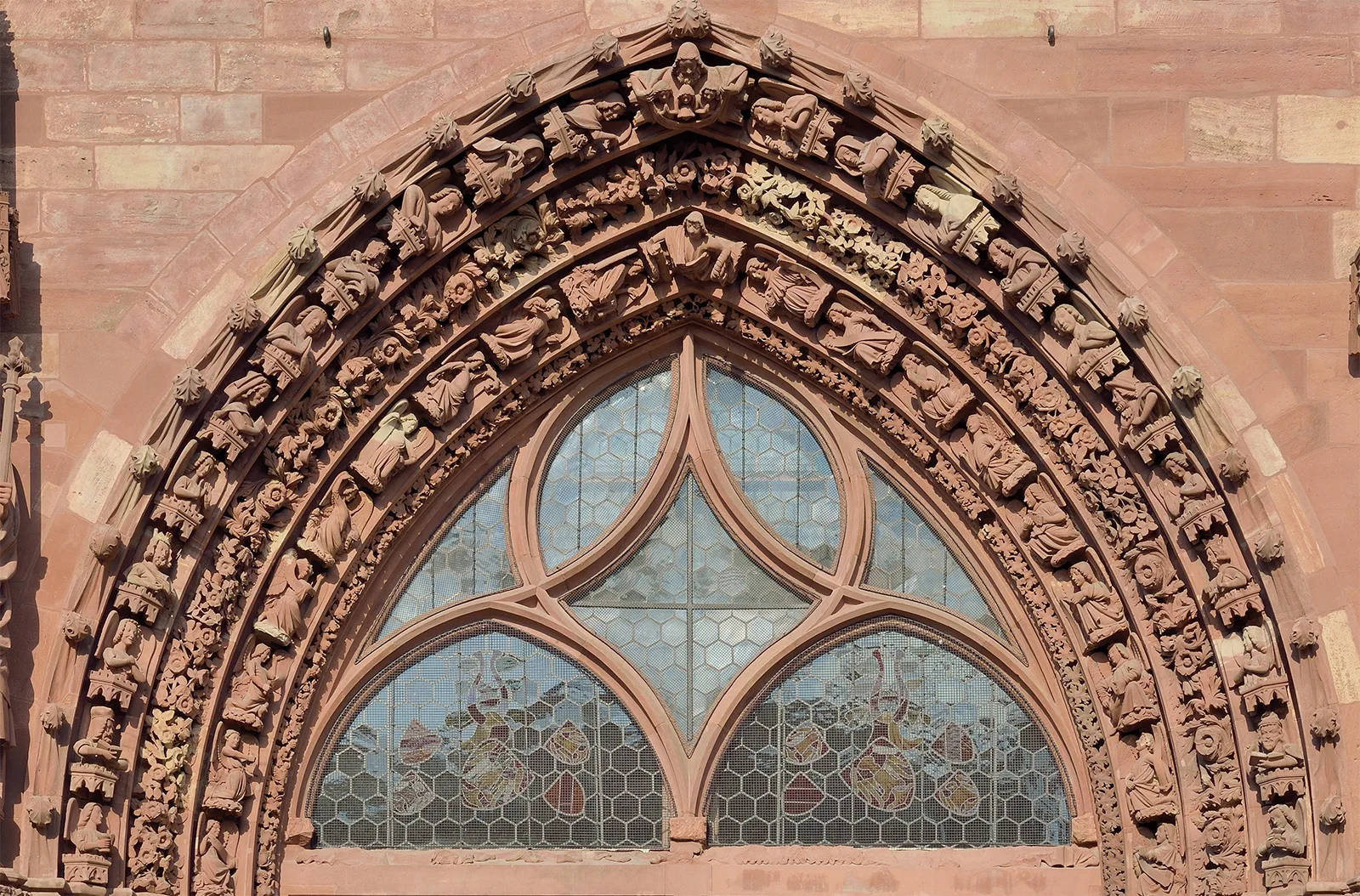

Felix and Regula – interim special status for Zurich’s patron saints

The Last Judgement – perplexing arbitrariness

Exceptions to the rule

George – chivalric bravery in the fight against evil

Martin – compassion that touches both parties

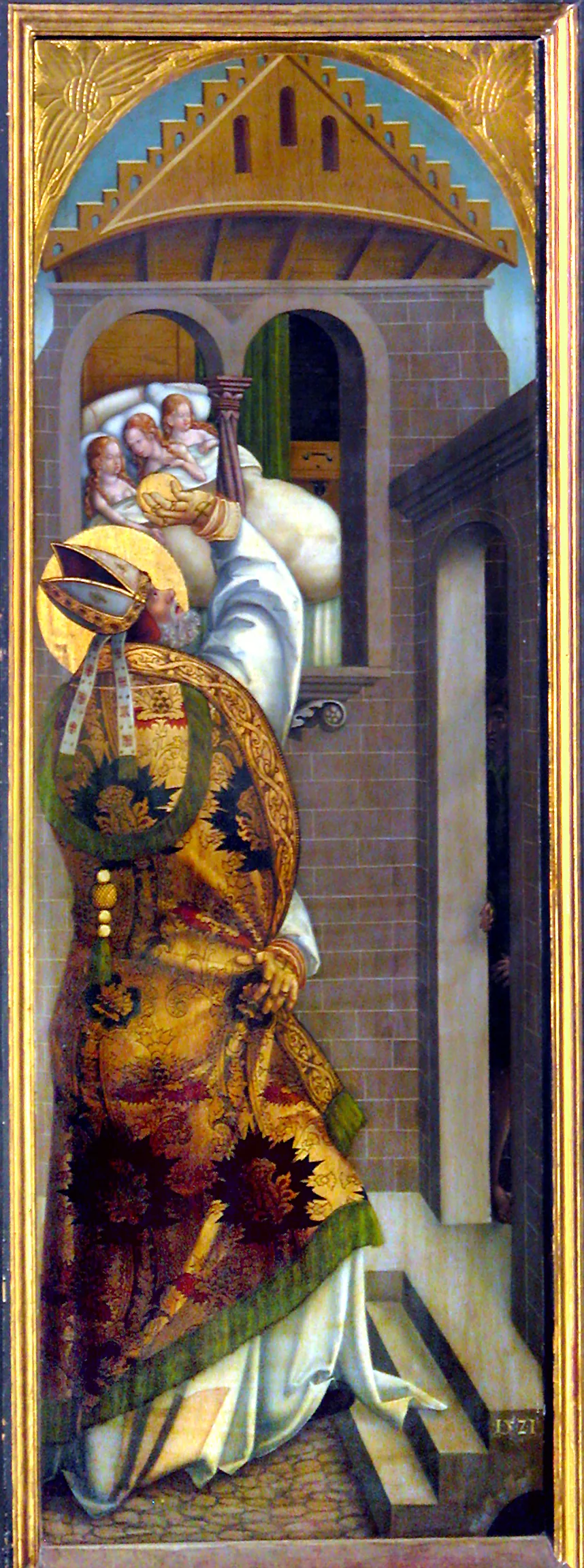

Nicholas – not everything depends on gold