The Marian Exiles in Switzerland

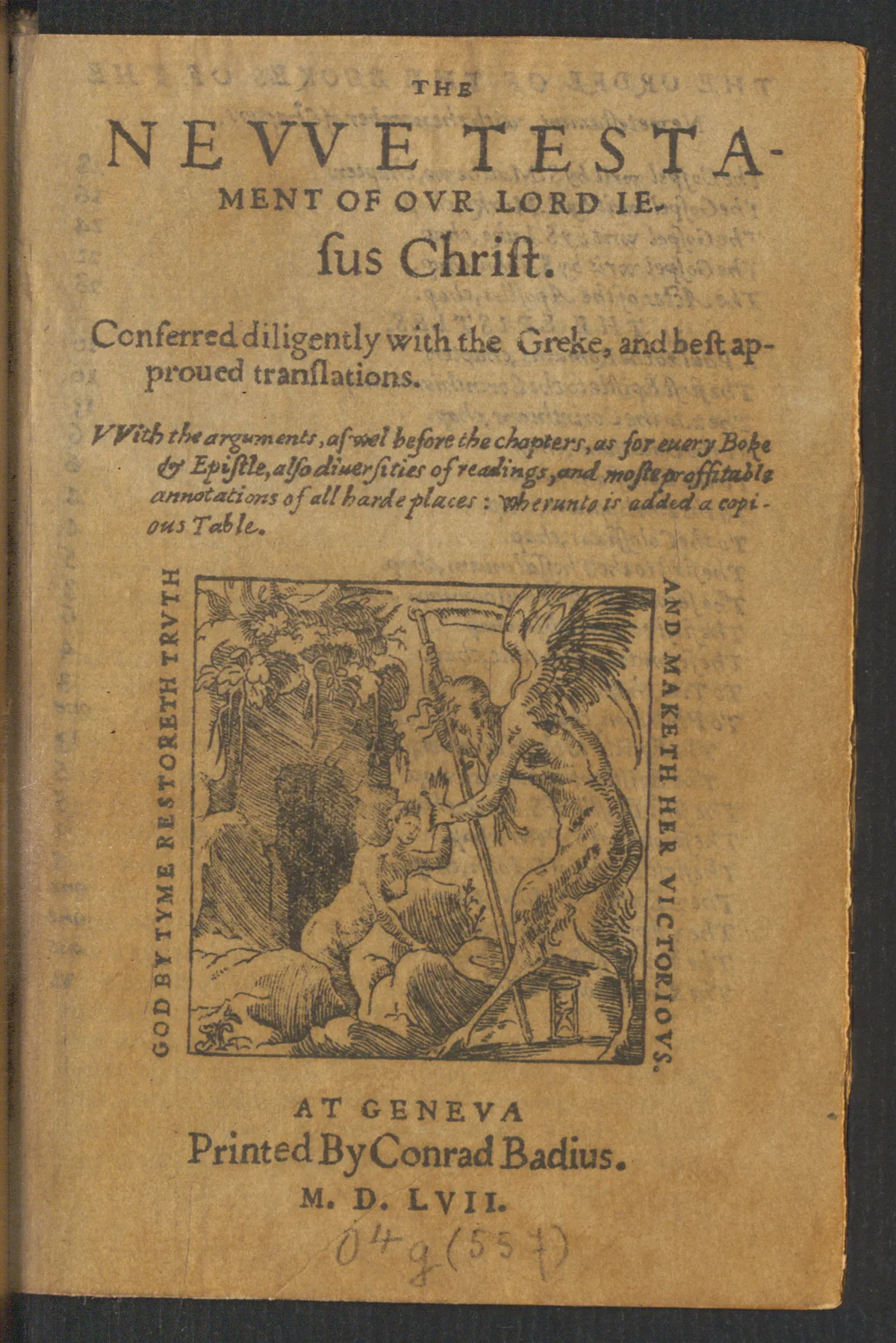

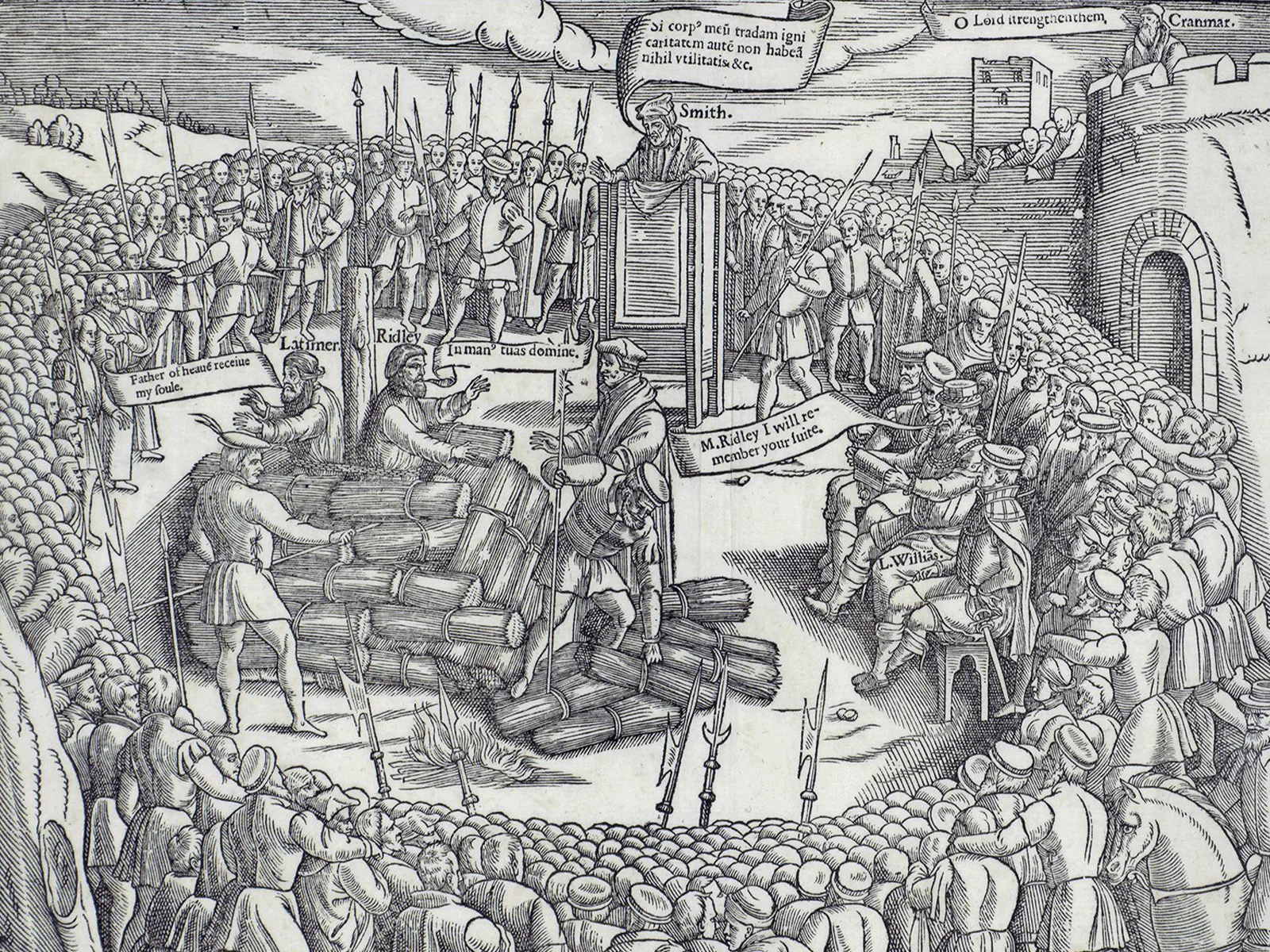

After Queen Mary's accession to the throne in 1553, numerous Protestant reformers went into exile in Switzerland. These so-called "Marian exiles" later exerted a great influence on English politics and cultural life.

Ties between England and the old Swiss confederation

English Protestants in Swiss exile

An enduring legacy