Zentralbibliothek Zürich

The birth of the tabloid media

With the advent of printing, from the late 15th century onwards printed news reports could be produced and circulated for the masses. Many of these news items were unusual stories, which also sometimes spread fear and panic.

Pamphlets were the first mass media in history. From the late 15th century onwards, they brought printed news reports to the masses. Often these reports were illustrated, because very few people could read in those days and so the only effective way to communicate was with pictures.

A lot of the pamphlets reported on celestial phenomena – for example, the news of a halo around the sun that appeared over Nuremberg on 12 May 1556. Such depictions, skilfully carved into wood and coloured by hand, are quite beautiful, sometimes even decorative, to the modern eye. There are simple physical explanations for virtually all these phenomena. In this particular case, it was ice crystals that had created a halo around the sun. However, the author of the pamphlet saw it as a sign from heaven and a warning not to stray from the true faith. The ‘true faith’ at that time was the Protestant faith that Martin Luther had preached.

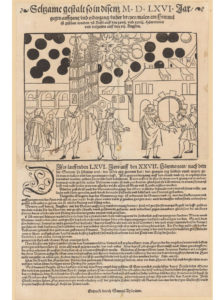

The pattern is repeated in other broadsheets produced from woodcuts, such as a 1566 print from Basel that has survived only in a black and white version. This print depicts spherical phenomena in the skies for which there is still no scientific explanation. This event cannot have been some kind of delusion, however, since there are other reports of similar sightings in contemporary literature. In this case too, these celestial phenomena are interpreted as a divine omen. The author is calling on his audience to repent and pray for divine assistance against the Turks.

Solar halo over Nuremberg, 1556.

Zentralbibliothek Zürich

Spherical phenomena in Basel, 1566.

Zentralbibliothek Zürich

Almost as puzzling is a story dating from 23 March 1550 depicting grain raining from the sky in Carinthia. It is said that for two hours grain rained down from the sky – local peasants milled the grain and used it to bake bread. The story proved so popular with the local ‘readership’ that the pamphlet was reprinted in other regions as well. In the 19th century, a plausible explanation was found for this phenomenon: the ‘grain’ was a type of lichen that had been blown a long distance by the wind. In the 16th century, people didn’t know about this. For them it was the biblical manna that fell from heaven, and of course that too was a divine omen. Swarms of locusts also fell out of the sky. They caused fear and terror, and are depicted in appropriately dramatic scenes.

THE COLLECTION OF A ZURICH PASTOR

These pamphlets wouldn’t have survived if they had not been carefully assembled and kept in a safe place by a 16th-century observer, Zurich clergyman Johann Jakob Wick (1522-1588). He was supported in his collecting activities by Zwingli’s successor, Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575). Like many of his contemporaries, Wick was appalled by the turmoil and atrocities of the Reformation, and he collected the signs of his times over a period of 30 years. For Jakob Wick, these dramatic events were harbingers of the End Times. Considered objectively, these reports were pieces of news, but no one bothered to distinguish between true and false, facts and hearsay. On the contrary: the bigger a story was, the more it seemed to back up the honest intentions of the mostly anonymous authors. There’s no denying a parallel to ‘fake news’ and the tabloid press of the 20th century.

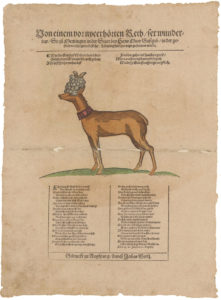

Wickiana, Jakob Wick’s collection, is thus more topical than you might think at first glance. Strange things in the sky are by no means the only accounts the Zurich collector assembled: there are also reports of witch burnings, conflagrations, and a terrible explosion in the gunpowder magazine at Temesvár, Hungary (now Timișoara, in Romania) in 1576. Reports of birth defects in humans and animals also attracted a lot of attention in those days. And here too, people’s interpretations were a far cry from scientific explanations. Deformities were also seen in plants. Numerous accounts of miraculous ears of grain have survived, but there is also a report of deformed antlers on a deer.

Misshapen deer antler.

Zentralbibliothek Zürich

The most bizarre from today’s perspective, however, are the dramatic representations illustrating the polemics of the Protestant Reformation. A Jesuit school is depicted as a gathering of animals. The Pope appears as a big ugly pig, known as the Papstsau, an allusion to Pope Paul IV (1476-1559). The Pope was a fervent supporter of the Inquisition, and an anti-Judaist. The pupils are dogs, being taught by other dogs. This is probably a reference to the Freiburg Jesuit Peter Canisius (1521-1597); the name Canisius contains the Latin word for dog, canis. The Wickiana also illustrates the anti-Semitism that was rampant within the church at that time: for instance, there’s a picture of the execution of two Jews who allegedly tried to buy two Christian children for the purpose of committing a ritual murder.

The collection of pastor Johann Jakob Wick held in the Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Zurich Central Library) has been carefully maintained since the Reformation. It comprises 25 volumes with more than 1,000 illustrations. In 1925, the 431 single-leaf broadsheets were removed from the bound volumes so that they could be better conserved. Both the hand-written volumes and the single-leaf broadsheets are digitalised and freely accessible. They are among the institution’s most sought-after holdings. Over the next few months, it is planned to revise the indexing, so that access to the broadsheets will be even easier.

Reformation polemic against the Jesuits – in the centre of the picture is the Papstsau, a popular motif at that time.

Zentralbibliothek Zürich

Report on the birth of a deformed, two-headed calf, dating from 1555.

Zentralbibliothek Zürich