The thunder of cannon at Fribourg’s gates

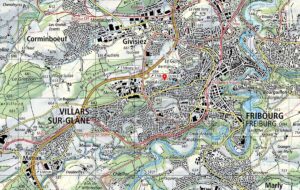

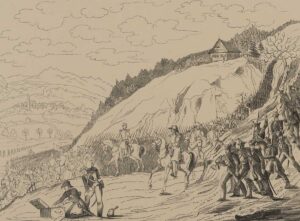

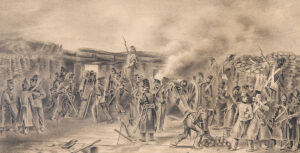

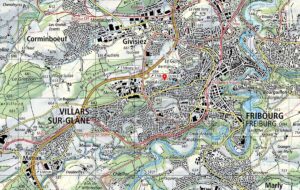

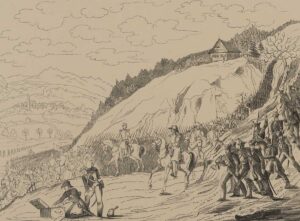

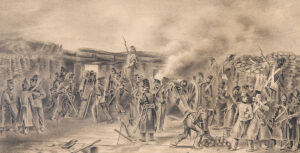

Today allotment gardens bloom and flourish there, but in November 1847 the thunder of cannonfire filled the air. The story of an almost forgotten theatre of war on Fribourg’s doorstep.

Today allotment gardens bloom and flourish there, but in November 1847 the thunder of cannonfire filled the air. The story of an almost forgotten theatre of war on Fribourg’s doorstep.