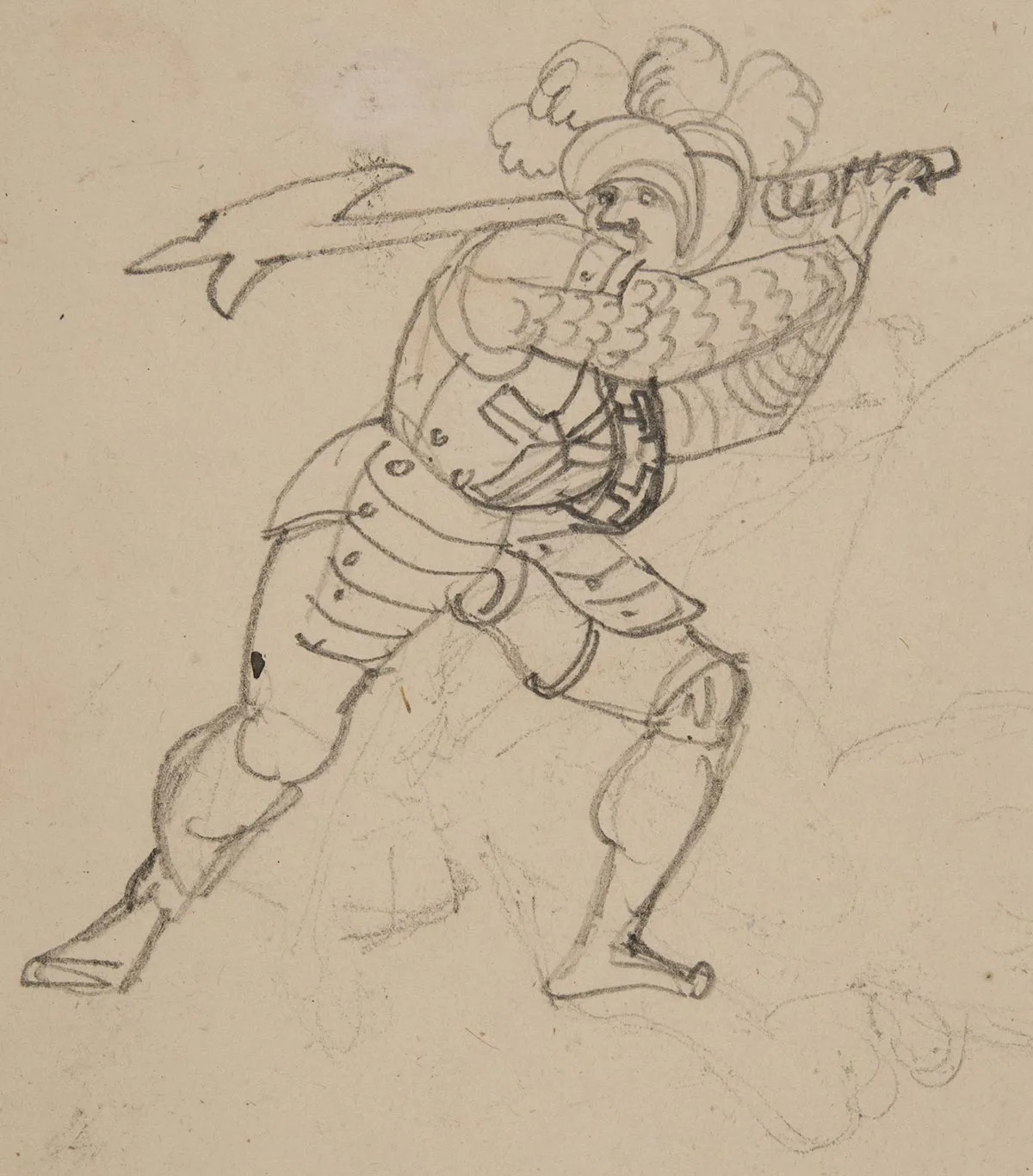

The rise of an all-purpose weapon

In the Middle Ages, forces were distributed unevenly. On one side, the armour-clad knight; on the other, the simple peasant farmer. But with the invention of the halberd, the tables were turned…

Characteristics and use of a halberd

The possible origins of the halberd

Further development

A halberd renaissance