World-famous typefaces from Kriens

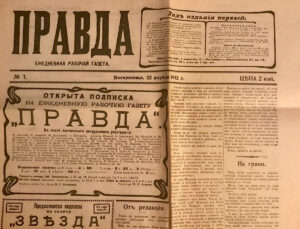

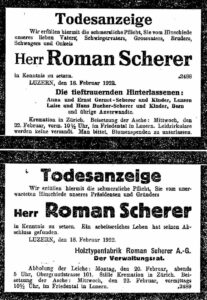

Roman Scherer’s highly specialised factory in Kriens manufactured wood type for the whole world – including for Pravda, the official newspaper of Russia’s Communist party in Moscow.

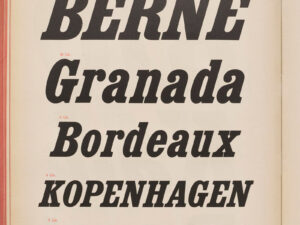

Film by the Letterform Archive in San Francisco on a catalogue from 1920. It provides a good insight into Roman Scherer’s wide range of different typefaces. Letterform Archive