Peace at last!

After more than four years of violent conflict, the First World War came to an end on 11 November 1918. Social tensions in Switzerland had intensified drastically and culminated the next day in the general strike.

Around the turn of the year 1916/17, various calls for peace briefly sparked hopes for an end to the war. The German Empire’s declaration of unrestricted submarine war in February 1917 brought these hopes to an abrupt end.

The budding hopes for peace had led a number of Swiss pacifist groups to form a committee in order to consolidate their efforts. However, the majority of French-speaking leaders of the Swiss Peace Society were still sceptical regarding peace talks. The declaration of unrestricted submarine war reinforced their view that the German government obviously favoured military action over negotiation. After all, they had set their hopes on democracy and justice prevailing over authoritarianism and militarism. There could be no talk of a unified peace programme within the Swiss peace movement.

THE IDEA OF A LEAGUE OF NATIONS

On 22 January 1917, Woodrow Wilson’s address to the US Congress – “Peace Without Victory” – made history. The main subject of the speech was his proposal to create an international organisation – a “League of Nations” – that would guarantee a lasting order of peace in the future. This proposal was enthusiastically welcomed by the Swiss pacifists and, after the US entered the war, led to increased support for the Entente-friendly elements of the Swiss Peace Society. A few months after Gustave Ador of Geneva had replaced the pro-German Arthur Hoffmann on the Federal Council, a statute revision was passed in October 1917 at a delegates’ assembly in Olten. This included the stipulation that a French-speaking member take over as head of the Swiss Peace Society at the next election.

ANTIMILITARISM AND CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION

The seemingly never-ending war, officer scandals, active service consisting largely of drills and the poor supply situation all contributed to growing antimilitarism in the Swiss labour movement. In the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland, this development finally led to a rejection of national defence in the course of two peace conferences held in Zimmerwald and Kiental in June 1917. In the second half of the war, there were also an increasing number of conscientious objectors. They voiced the desire to find radical new ways to coexist peacefully. The middle-class-based Swiss Peace Society, on the other hand, rejected this approach to achieving world peace. Its peace discourse, which focused strongly on international law, and its patriotic commitment to Switzerland distinguished the Swiss Peace Society from the pacifism of antimilitarists and conscientious objectors, who were opposed to the use of force in general. This rejection of violence played a major role in promoting Wilson’s proposed idea of founding a League of Nations. Its Entente-friendly Geneva section included professors William E. Rappard, Paul Moriaud, Charles Borgeaud, international law expert Otfried Nippold and Gustave Ador as honorary members, who played a decisive role in making Geneva the seat of the League of Nations.

ARMISTICE AND GENERAL STRIKE

On 11 November 1918, the armistice was signed in a railway carriage in Compiègne, France. Following a sharp rise in social tensions in Switzerland, these culminated in the general strike at the end of the war. The dominant conflict between the linguistic regions throughout the war was superseded by a social divide between the working class and the bourgeoisie during the strike. Most workers in the cities regarded the strikers’ demands as long overdue, for instance the call for an immediate National Councillor re-election with proportional representation, women’s active and passive suffrage, the introduction of the 48-hour work week and pension and disability insurance. However, the leaders of the middle-class Swiss Peace Society rejected any strike on principle as a means of solving social issues.

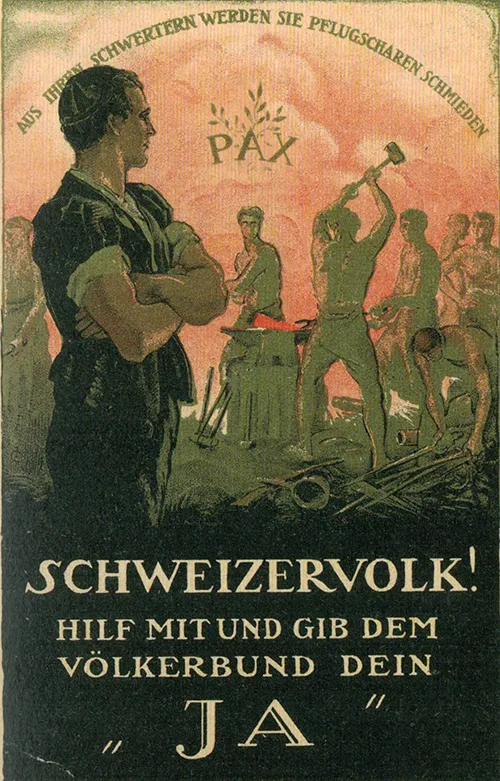

THE VOTE TO JOIN THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS

On 28 April 1919, Geneva was chosen as the seat of the League of Nations and thus became a major centre for international relations. However, it was by no means clear whether the Swiss even wanted to join this new “nation league”. The narrow decision in favour of joining was the result of enthusiastic support from French-speaking Switzerland. German-speaking Switzerland, on the other hand, rejected joining altogether because it regarded the League of Nations as an executive body of the victorious powers. The resolution barely passed with a cantonal majority: 11½ cantons were in favour, 10½ against. If 94 Appenzeller (Innerrhoden) residents had voted differently, Switzerland would not have become a member of the first international organisation for collective peacekeeping.

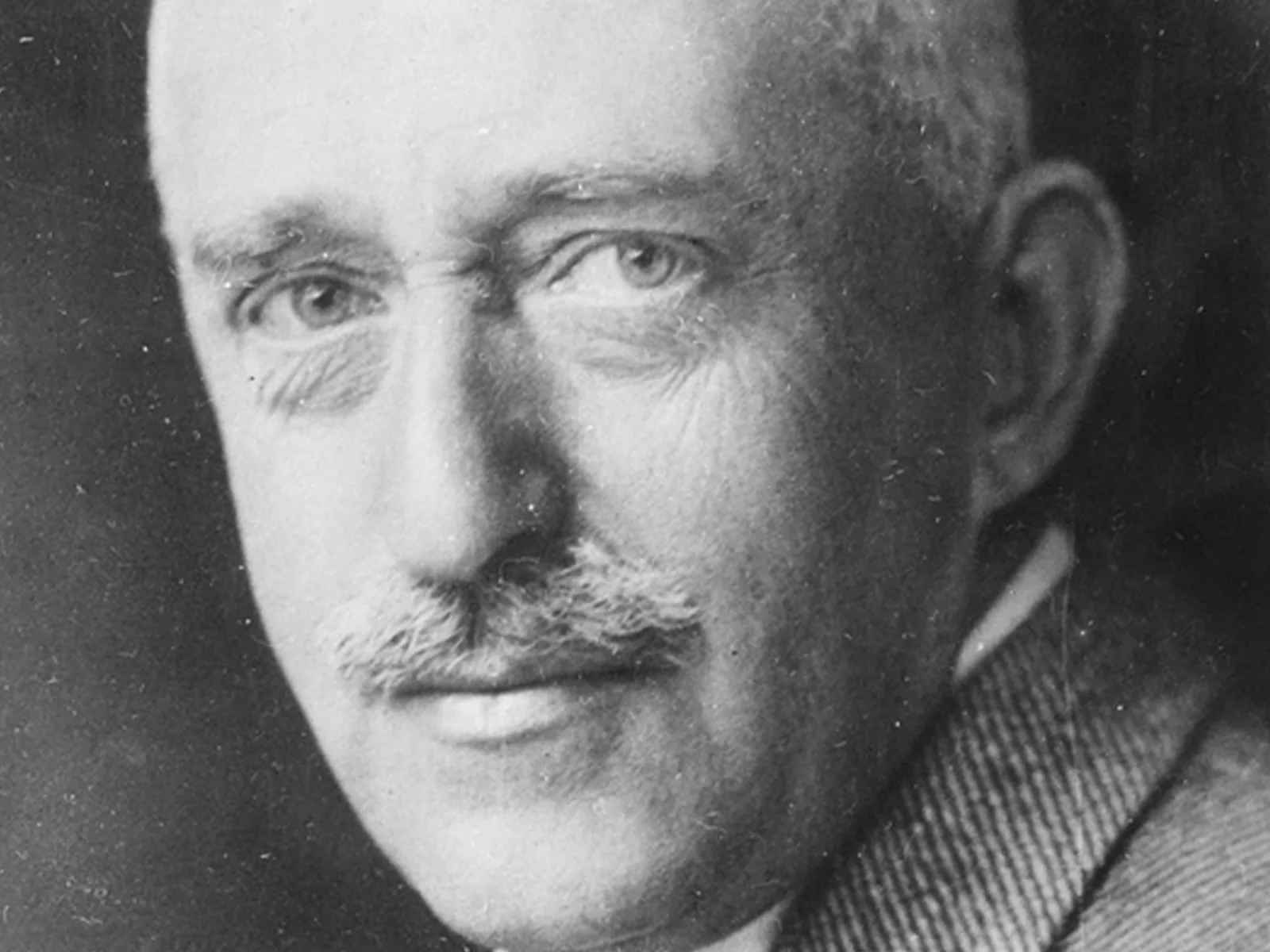

Gustave Ador. United Nations Archives at Geneva

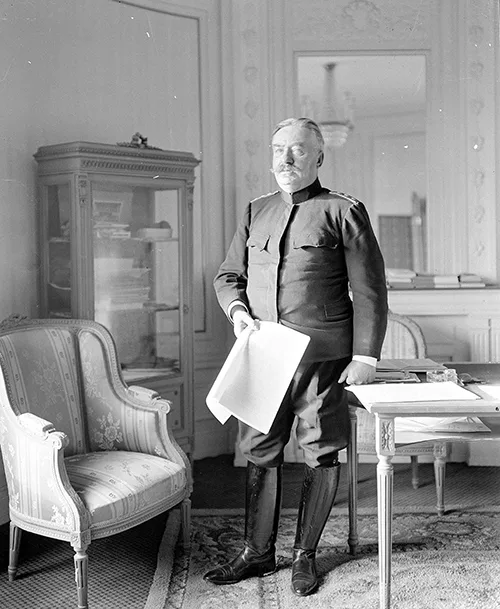

The German-friendly General Ulrich Wille advocated a Swiss army based on the Prussian model. He was therefore an especially controversial figure in French-speaking Switzerland and in left-wing circles.

Poster in support of joining the League of Nations. Private collection of Ulrich Gribi, Büren a. A.

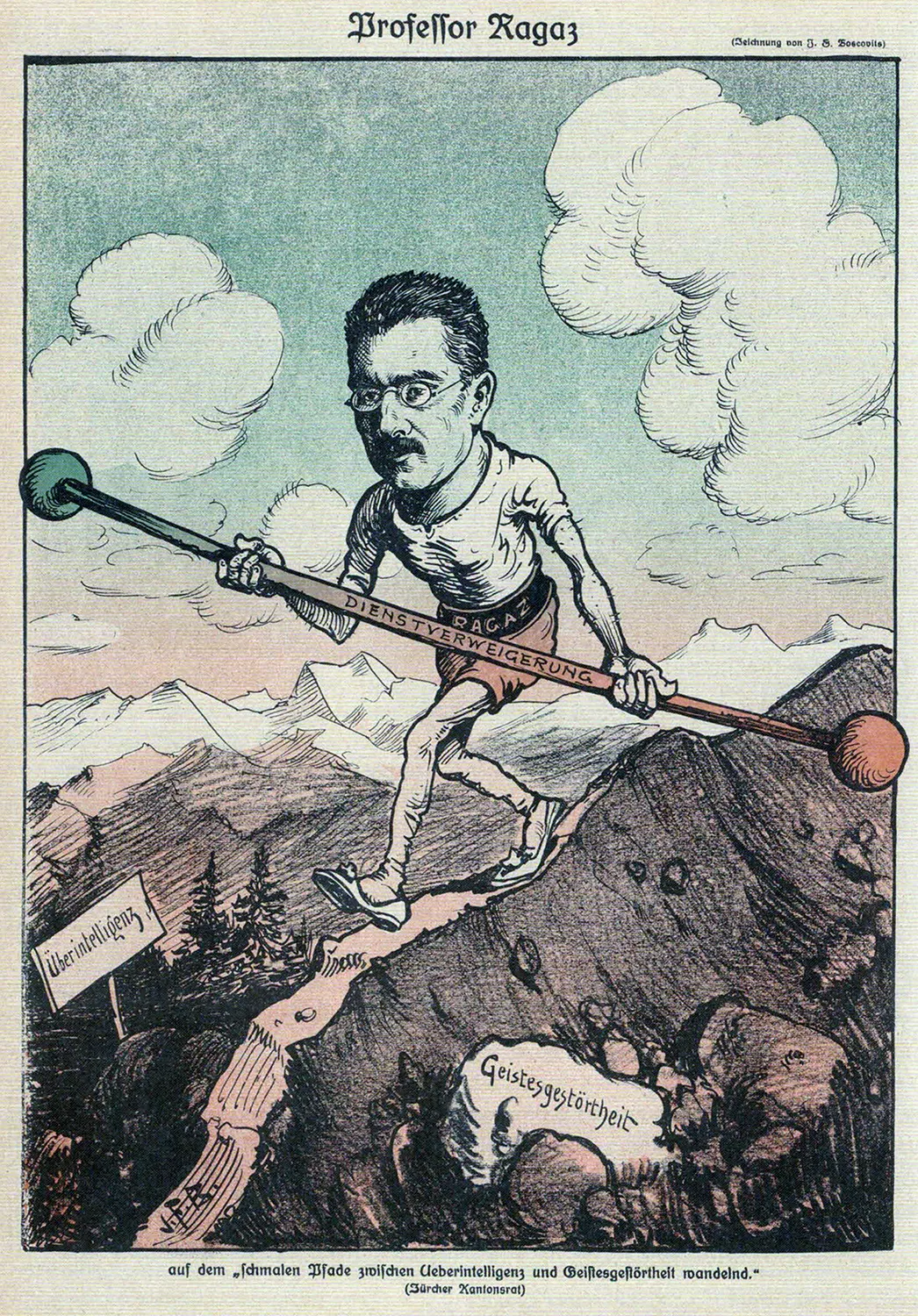

The ideational support of conscientious objectors by the religious socialist Leonhard Ragaz provoked resentment particularly in military circles. Even Nebelspalter magazine caricatured the theology professor as “walking a narrow path between hyper-intelligence and insanity”. Nebelspalter Verlag