© Gotthard Schuh / Fotostiftung Schweiz

The Swiss atomic bomb

After the Second World War, the fear of communism was also strong in Switzerland. For this reason, Switzerland made plans to build an atomic bomb of its own.

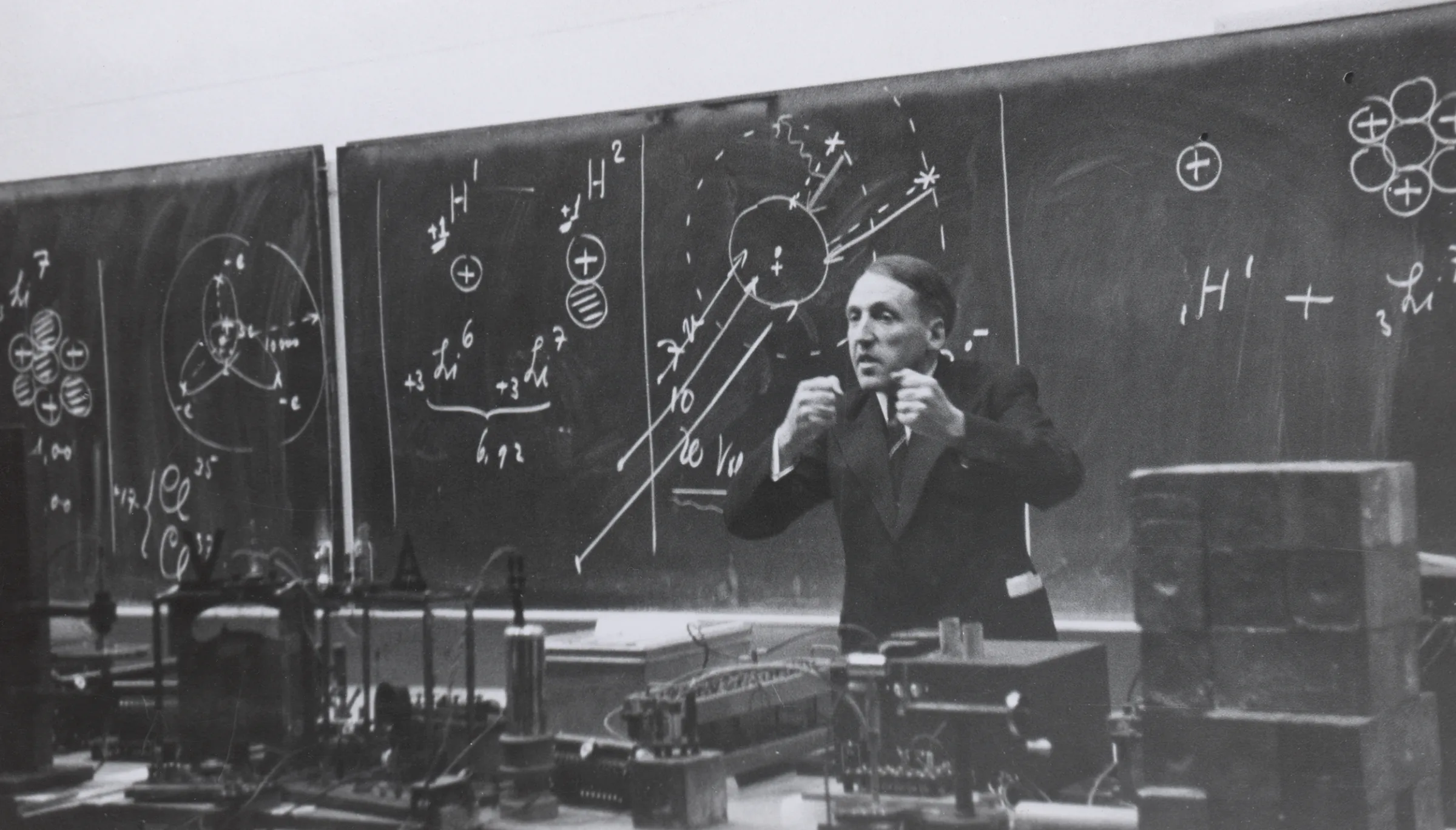

After atomic bombs were dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Swiss military leaders dreamed of supplying their army with nuclear weapons. On 5 November 1945, Federal Councillor Karl Kobelt summoned a conference at the Federal Palace during which the Study Commission on Atomic Energy (Studienkommission für Atomenergie, SKA) was founded. ETH Professor Paul Scherrer, head of the SKA, became a key figure in the Swiss nuclear weapons programme. Federal Councillor Kobelt issued the following order on 5 February 1946 in the confidential guidelines: “Furthermore, the SKA shall strive to develop a Swiss bomb or other suitable means of war based on the principle of atomic energy”.

FEAR OF THE SOVIET UNION

The Swiss army had entered the Cold War and feared a communist invasion or a nuclear attack by the Soviet Union. The inclusion of tactical nuclear weapons in NATO’s defence plans led to a growing demand in the mid-1950s among Swiss officers for nuclear weapons of their own. Following the 1956 Hungarian uprising, anti-communism reached its peak in Switzerland. At the Swiss Commission for National Defence meeting on 29 November 1957, the secret military plans were finally discussed openly. Divisional general and air force and air defence commander Etienne Primault stated: “If we had an airplane like the Mirage, for example, that was capable of flying to Moscow with atomic bombs, a deployment in enemy territory would be feasible. The enemy would then be perfectly aware that they wouldn’t just be bombed once they cross the Rhine, but that bombs would also be dropped in their own country”.

One of the most delicate issues in these military simulations was the question of using nuclear weapons on home soil. During the discussion, Chief of General Staff Louis de Montmollin commented that there are cases where nuclear weapons absolutely must be used, even if there is a risk that the civilian population will suffer considerable harm. He argued that consideration for the public alone was not reason enough to take this option off the table.

Federal Councillor Karl Kobelt at the Geneva Motor Show, 1952.

Swiss National Museum / ASL

Demonstration against the atomic bomb in Lausanne, 1959.

Swiss National Museum / ASL

Anti-communism unleashed a dangerous megalomania among some Swiss army leaders. The deployment of nuclear weapons on Switzerland’s own territory would have had devastating consequences for the population of such a small and densely populated country. On 11 July 1958, the Federal Council also issued a statement that explicitly advocated equipping the country with atomic bombs. “In keeping with our centuries-old tradition of military defensiveness, the Federal Council holds the view that the army must be provided with the most effective weapons in order to preserve our independence and protect our neutrality. This includes nuclear weapons”. Pacifists protested against the atomic craze, but Swiss voters rejected a ban on nuclear weapons in 1962.

With the Mirage Affair of 1964, the high-flying dreams for a Swiss atomic bomb were unable to take off. Due to pressure from the superpowers, Switzerland was obliged to sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in 1969. Nevertheless, the secret nuclear weapons programme continued and was not officially shut down until 1988. The Swiss atomic bomb was just a paper tiger up until the end of the Cold War, as the numerous trials never progressed beyond the “theoretical possibility” stage. The lack of uranium, technological backwardness, the shortage of qualified scientists and limited financial resources prevented Switzerland’s dream of having its own atomic bomb from coming true.

“Little Boy” the atomic bomb on a holding rack on Tinian Island just before being loaded into Enola Gay’s bomb bay.

Wikimedia