PTT Archive, Tele_167_0069

Please connect me! Automating our telephone exchanges

On 3 December 1959, PTT replaced Switzerland’s last manual telephone exchange with a fully automated switching system. This major feat of engineering also signalled the end of the switchboard girl, or ‘Fräulein vom Amt’, as the telephone operators were known.

Shortly after the turn of the century, the automation of call transferring began in Europe. It was the Kaiserlichen Telegrafenverwaltungen, the imperial telegraph authorities in Germany and Austria, that started, early in the 20th century, equipping their exchanges with automated Strowger switching systems for the first time. They were endeavouring to cope with the skyrocketing number of telephone calls in their networks by partially automating the call switching. As in these neighbouring countries, after the turn of the century telephone traffic increased abruptly in Switzerland as well. What was at that time the Eidgenössische Telegraphen- und Telefonverwaltung (Swiss Telegraph and Telephone Agency) therefore felt under some pressure to modernise and enlarge its manual telephone exchanges, and adapt them to the cutting edge of switching technology. The first semi-automatic switchboard in Switzerland was put into operation in Zurich-Hottingen in 1917.

After the initial experience with the semi-automatic switching system in the Zurich local exchange network, and faced with the continuing rapid increase in telephone traffic, the Swiss Telegraph and Telephone Agency decided in 1920 to fully automate call switching in all larger towns and cities. In particular, the exchanges in Zurich, Lausanne, Geneva, Bern and Basel were to move to fully automated operation as soon as possible. The first fully automatic telephone exchange in Switzerland was opened in Lausanne on 29 July 1923. A year later, the Geneva-Mont Blanc exchange was also fitted with a fully automated exchange system; St Gallen-Winkeln followed in 1925, and in 1926 Zurich-Hottingen also moved to fully automated operation. The reduction in call switching personnel and the unfailing reliability of the Strowger switches meant that, over the course of the next three decades, manual exchanges were also phased out in all other local exchange networks throughout Switzerland.

In the late 1920s, the newly organised Post-, Telefon- und Telegrafenbetriebe (PTT), the Postal Telegraph and Telephone Agency, sought to establish automatic call connection not just within but also between the local networks, using its ‘Städtewahl’ (city choice, or intercity) system. While a telephone connection to a different local exchange network had, until then, had to be placed by an outbound switchboard operator (in the caller’s network) and connected by an inbound switchboard operator (in the call recipient’s network), subscribers could now dial certain cross-network calls themselves. The first such fully automatically connected ‘intercity’ call was made on 29 March 1930 between the Bern and Biel local exchange networks. In the same year, subscribers were able to direct dial between Basel and Zurich as well. Since the connection was established straightaway in the ‘intercity’ system, it was already clear that, sooner or later, automatic switching would also operate between rural local exchange networks.

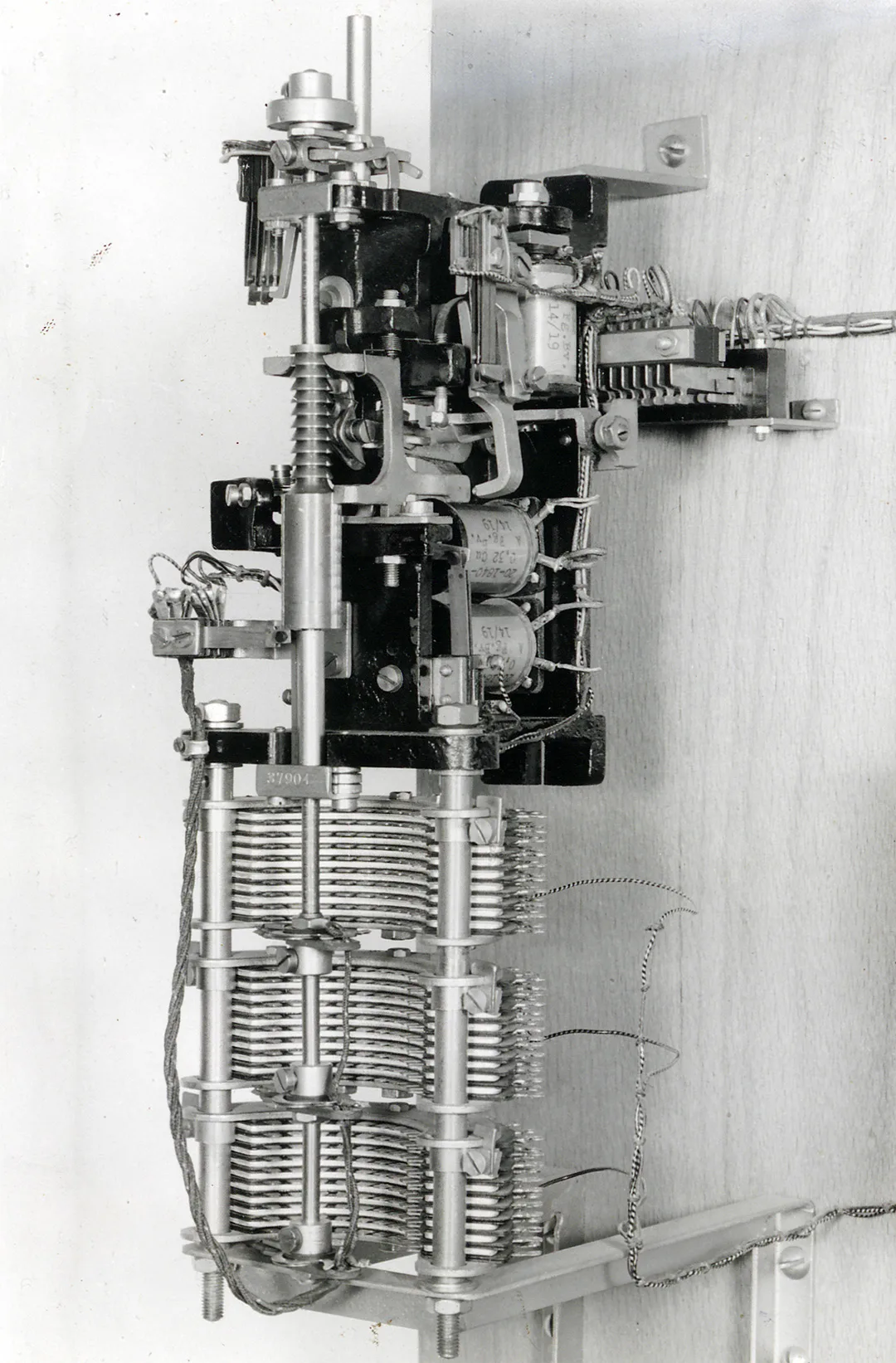

In 1917 automated Strowger switching systems were first used in Switzerland, in Zurich-Hottingen. They made semi-automatic switching possible for the first time.

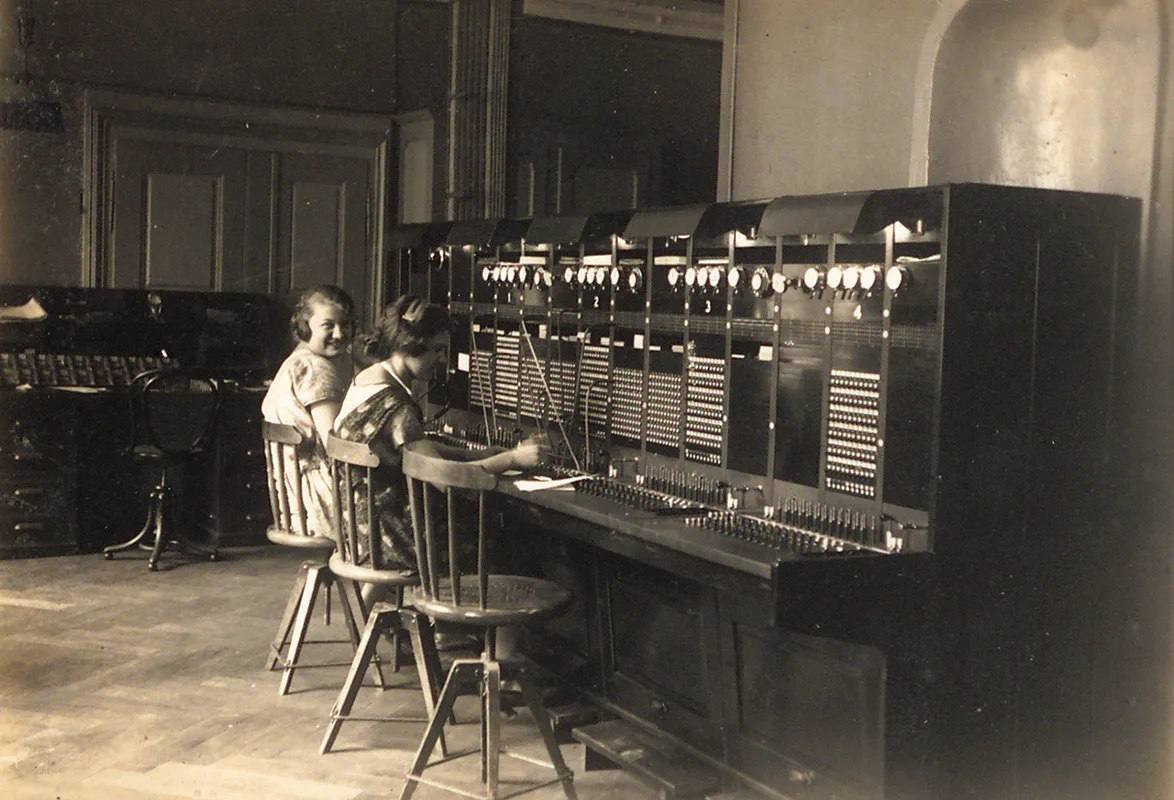

PTT Archive, T-00-C_Tele_184_0001

Switchboard operators at work on an already semi-automated exchange system, Porrentruy, in 1925.

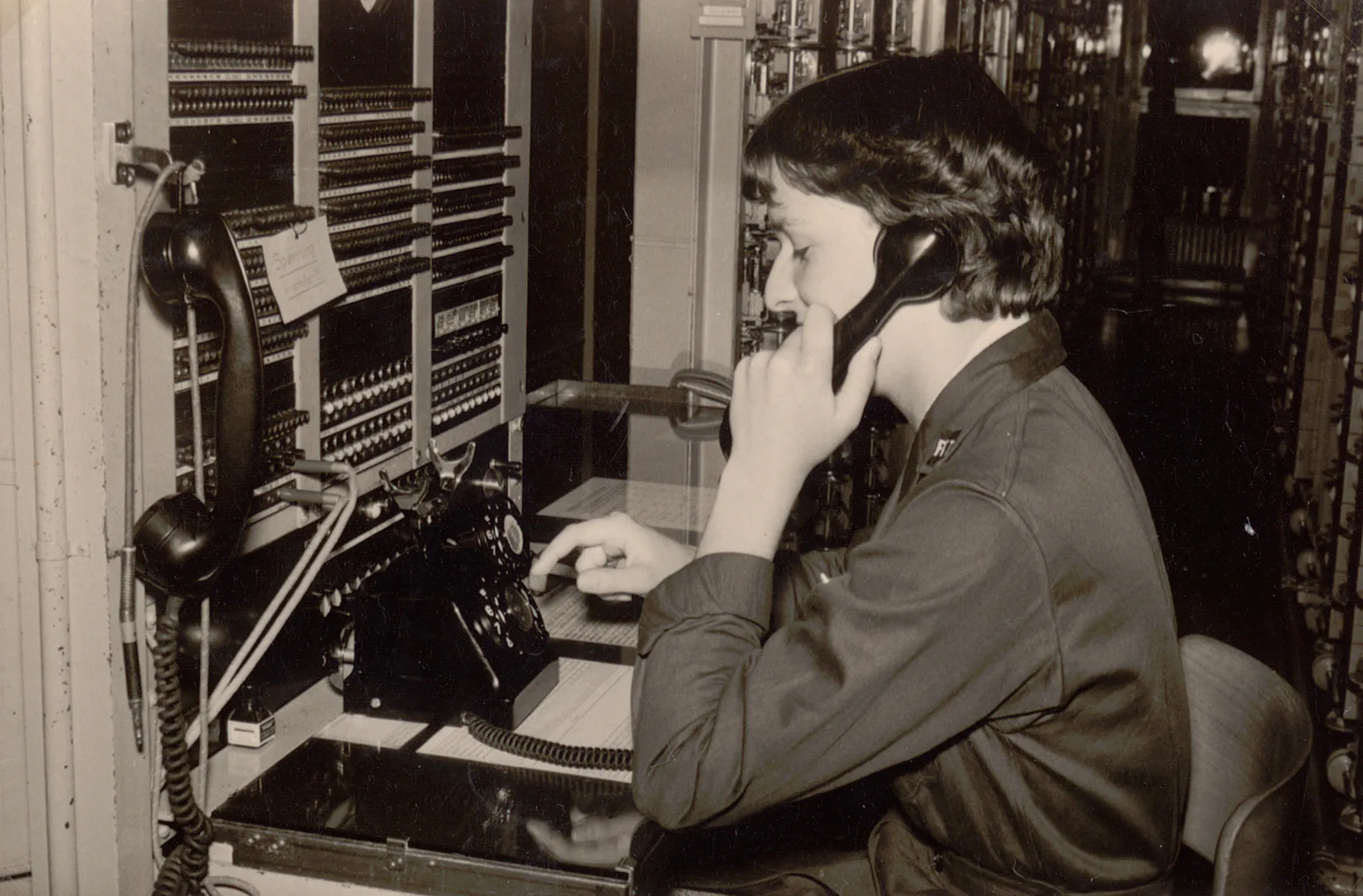

PTT Archive, Tele_179

Manual telephone switchboard in the Centrale du Stand, Geneva. Date unknown.

PTT Archive, Tele_167_0069

Switchboard operator at the Hottingen exchange, 1953.

Swiss National Museum

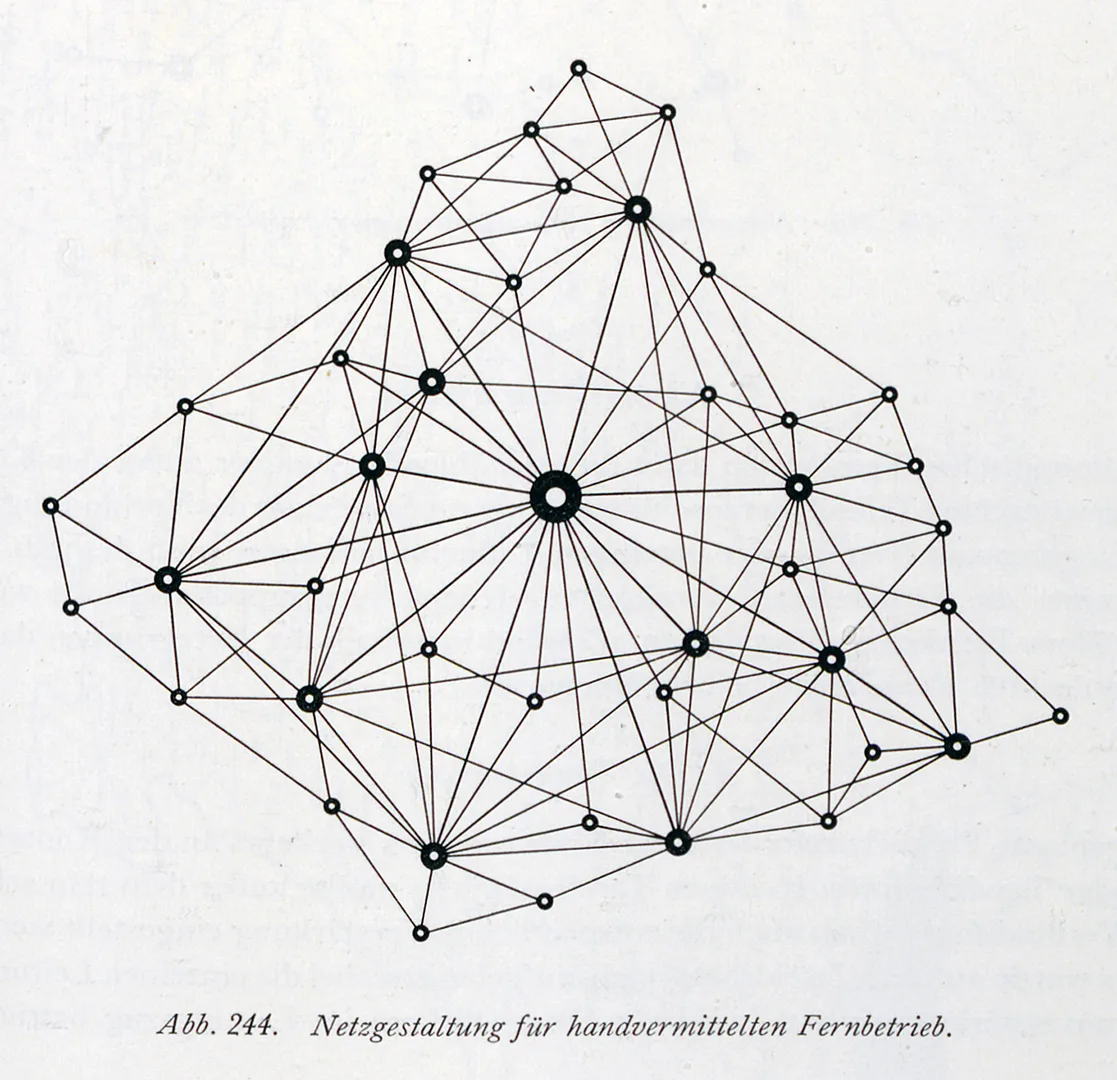

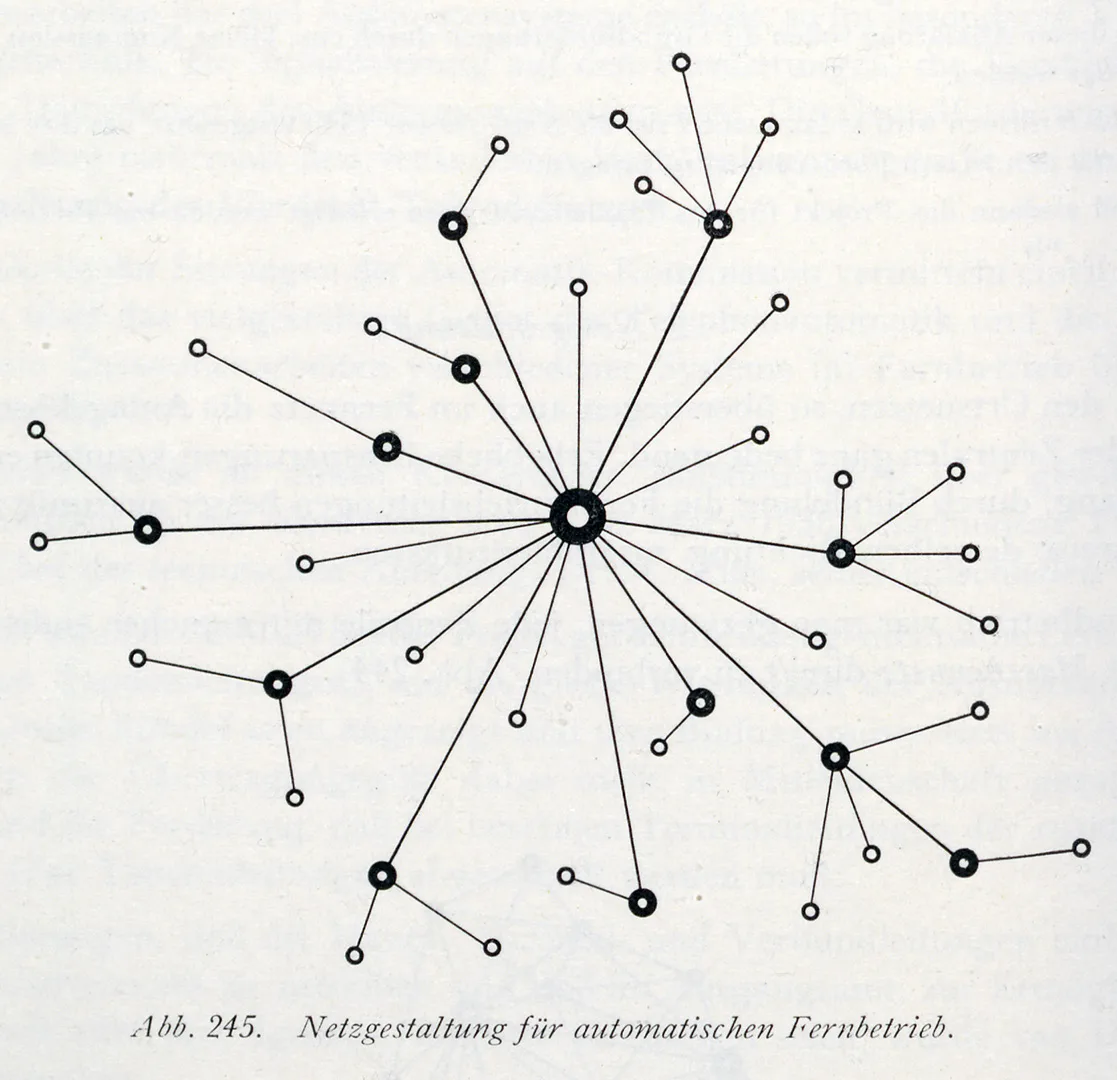

This foreseeable development soon eventuated: over the next two decades, the increasing automation of the country’s telephone exchanges radically altered the structure of Switzerland’s telephone network. Put simply, the PTT aimed to put through as many calls as possible, using as few telephone lines as possible. Rapid automation of the telephone exchanges made this much easier. Whereas in manual operation each telephone exchange in a ‘party line connection’ had had to be directly connected with numerous other exchanges, automatically connected calls could be bundled together at hubs and forwarded from there. Once automated, this type of centralised switching system functioned round the clock, and at a fraction of the previous operating costs. After the success of the first ‘intercity’ system, the PTT therefore put its automating efforts into reducing the number of lines, bundling calls via major hubs, and saving on the staff costs of the switchboard operators at its exchanges. The result was an automated star layout network which, by the date of its full automation on 3 December 1959, comprised around a million connections.

In a party line connection, manual exchanges are directly connected to as many other exchanges as possible.

PTT Archive, FC_2140

In a star network, fully automated exchanges are connected via specific hubs.

PTT Archive, FC_2140

In the PTT Archive in Köniz, there are sources dating from the 1930s and 1940s which reveal that the switchboard operators, shortly before they were laid off or moved to new positions due to the automation process, had to teach subscribers how to use their telephones now that they’d been fitted with dial plates (open PDF). Many switchboard operators had to go from house to house to help subscribers get over their fear of their new apparatus. After the local telephone exchanges were automated, these people had simply stopped making telephone calls – afraid they might do something wrong. In other networks, the switchboard operators were required to deliver ‘collective instruction sessions for the general public on automated networks’, sometimes with film presentations. These sessions were more or less well attended, depending on the weather and the progress of harvesting. The telephone exchange in Chur even explained subscribers’ lack of interest in the helpful demonstrations as being down to the ‘temperament of the Grisons native’. In the PTT Archive’s oral history project, Nelly Iseli-Dällenbach gives a first-hand account of the clumsy methods resorted to, and the inexpert use of the new apparatus by subscribers. The abrupt dismissals and relocations of the switchboard operators in the course of the automation process, and the important mediating role these women took on between the new technology and the wider population, deserve greater attention.

In the PTT Archive’s oral history project, staff of the former federal enterprise PTT talk about their past working lives, which continue to have an impact today. Among them is Ms Iseli-Dällenbach, who started working as a switchboard operator at the PTT in 1930 and experienced the automation of the telephone exchanges herself.

oralhistory-pttarchiv.ch