The Auguste Piccard Mésoscaphe submarine

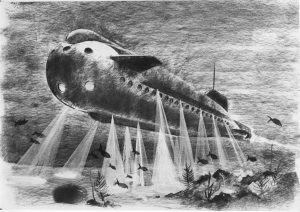

While there have been huge strides forward in exploring the universe, most of the underwater world is still a dark, closed book. The Piccard family has done significant pioneering work in exploring the bodies of water on our planet. The Mésoscaphe submarine descended into the depths of Lake Geneva and was deployed in the world’s oceans. This icon of engineering skill was one of the star attractions at the 1964 National Exhibition in Lausanne.

Symbol of Expo 64

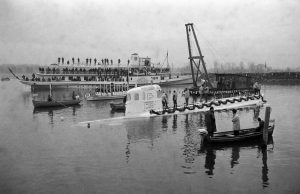

The Mésoscaphe was the big visitor drawcard at Expo 64. SRF

Adventure and treasure-hunting in America