Knocked off his pedestal

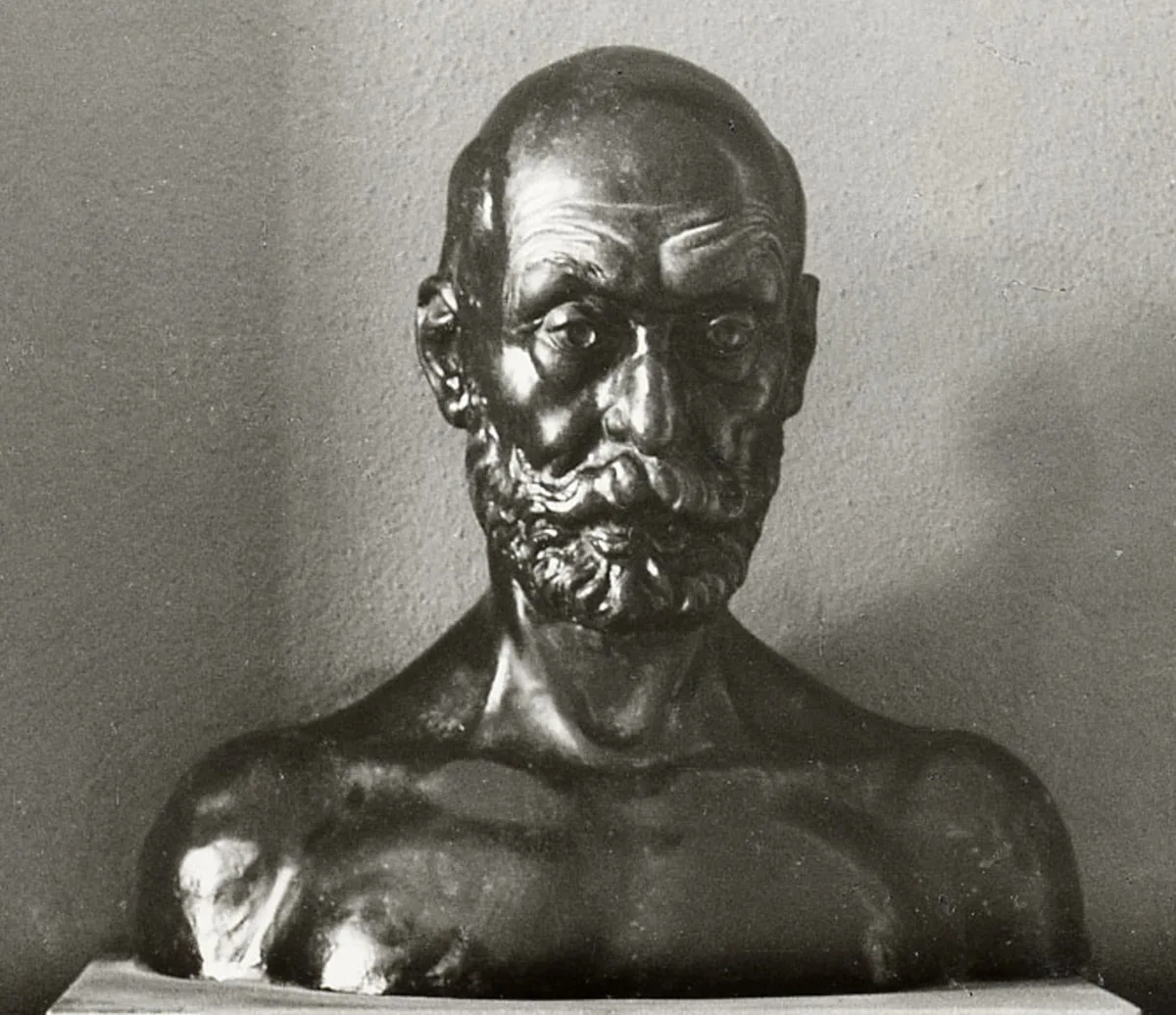

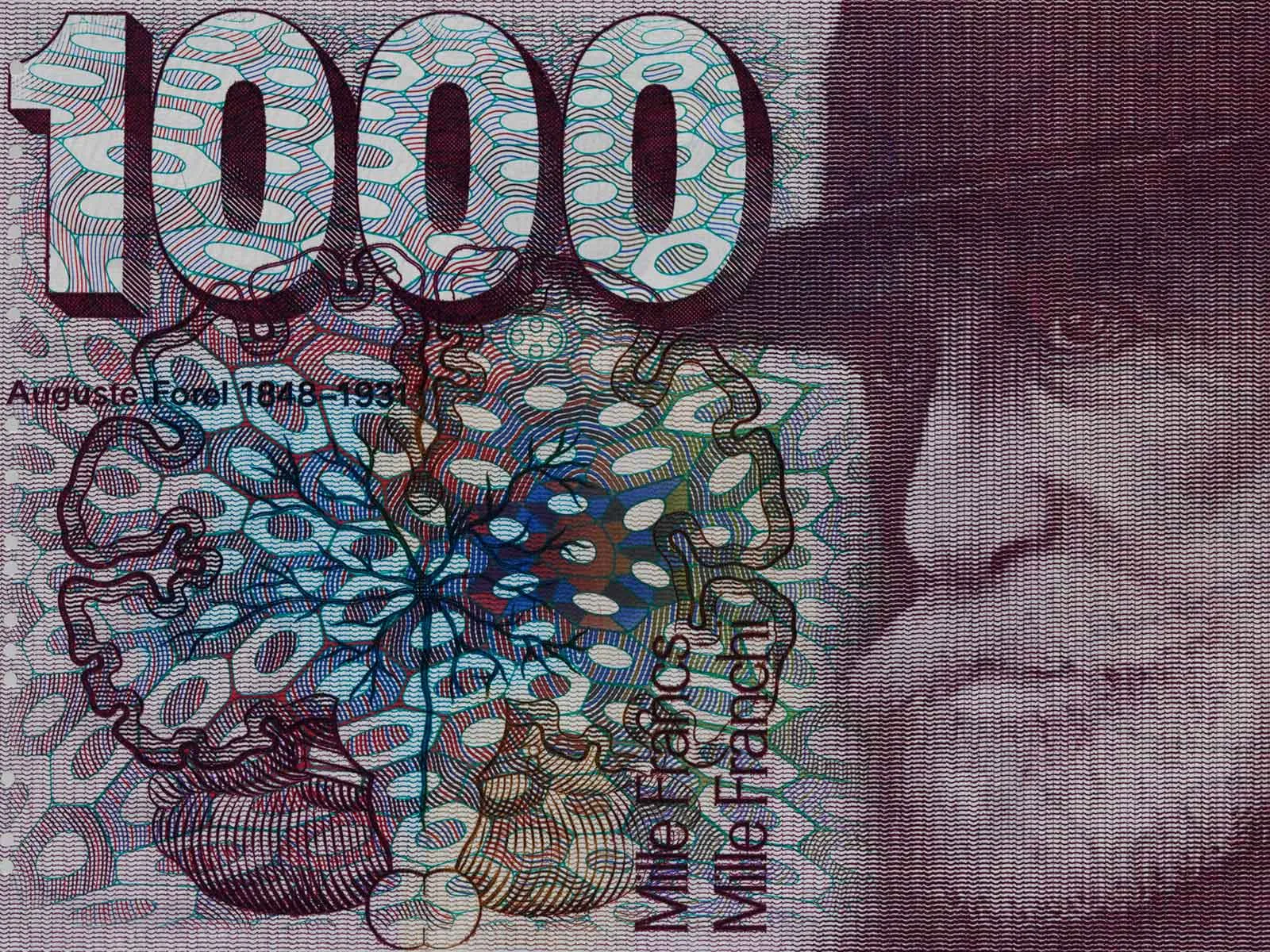

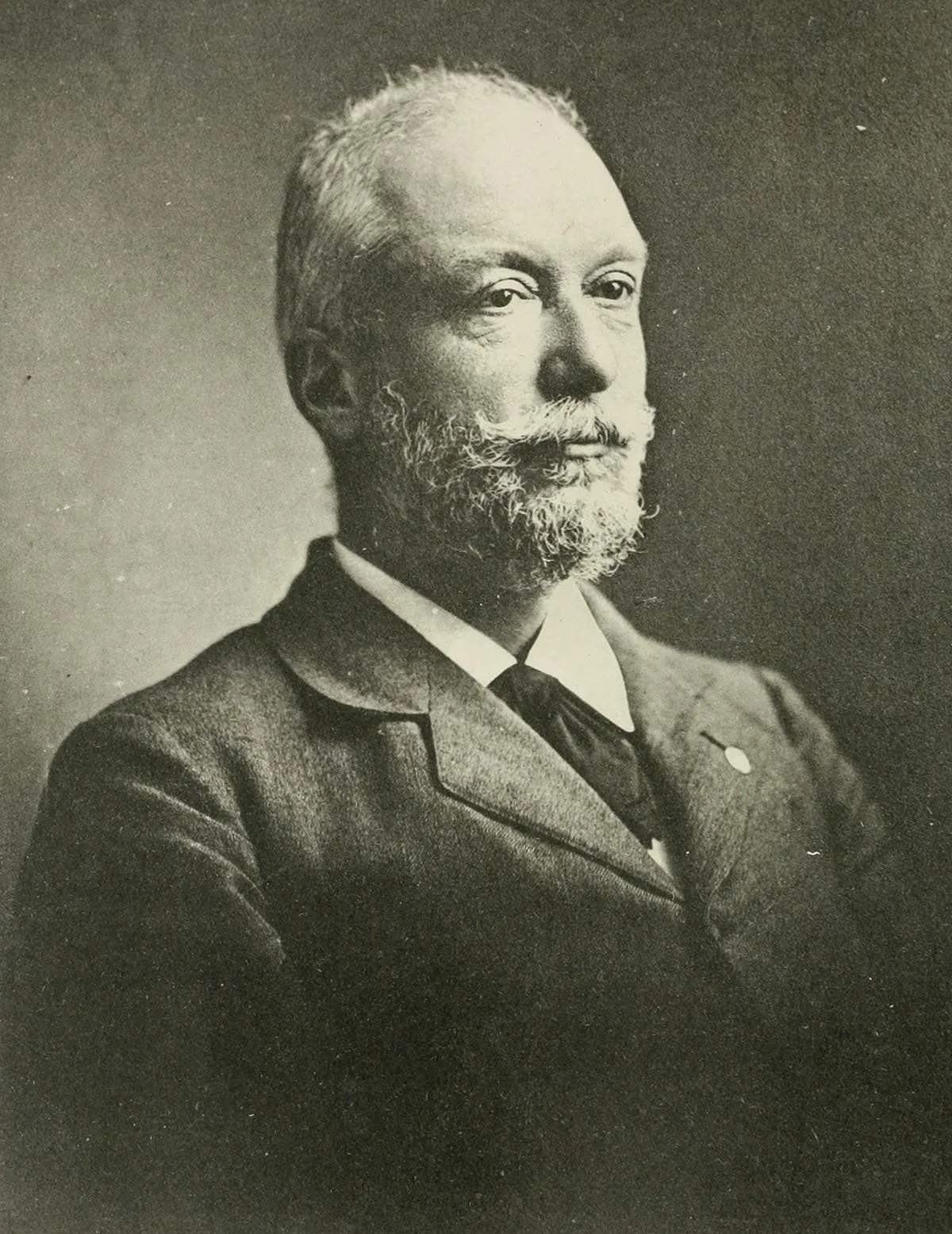

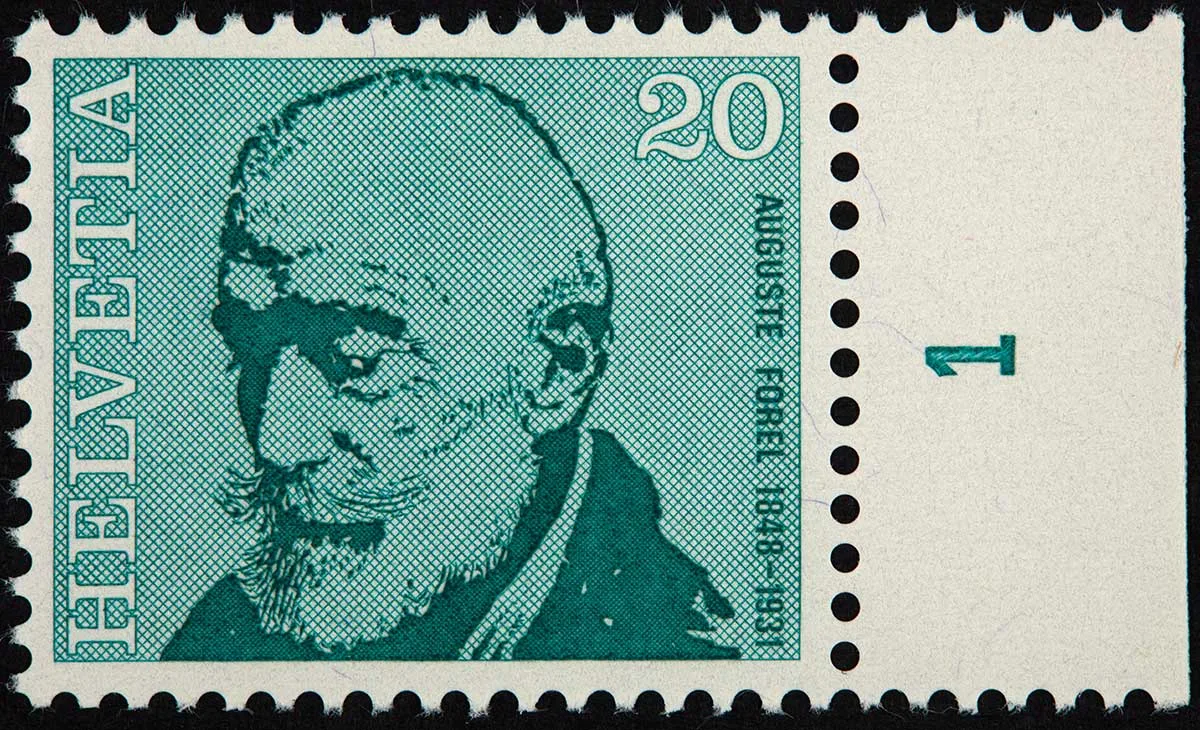

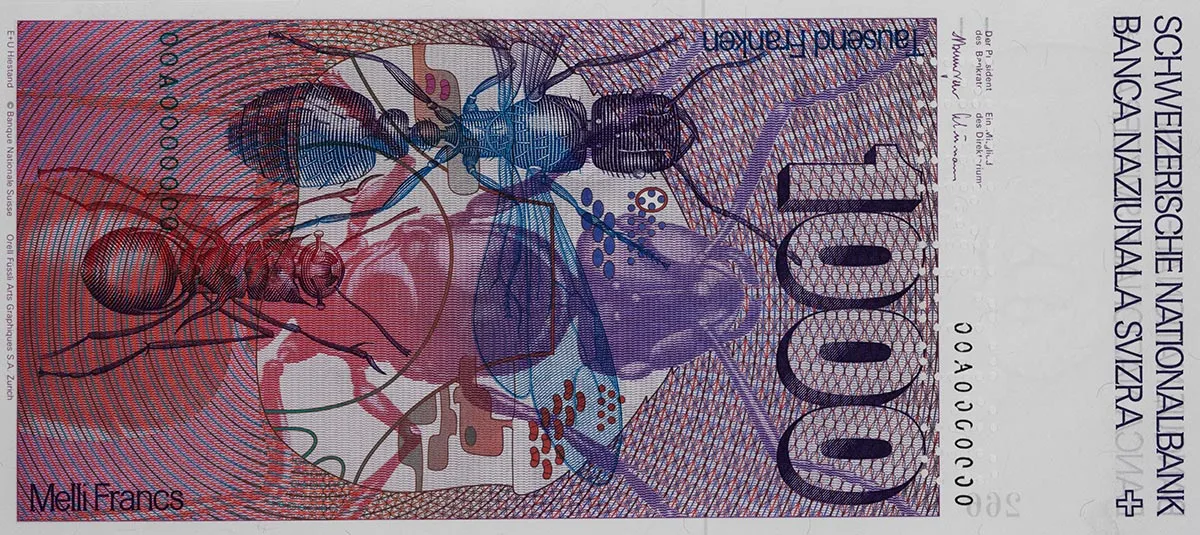

In the last-but-one series of Swiss banknotes, the thousand-franc note depicted Auguste Forel as a wise researcher turning his alert gaze on the world, as an icon of science and Helvetic national symbol. But this stylised heroic image failed to stand up to closer investigation. A story illustrating the pitfalls of the culture of commemoration.

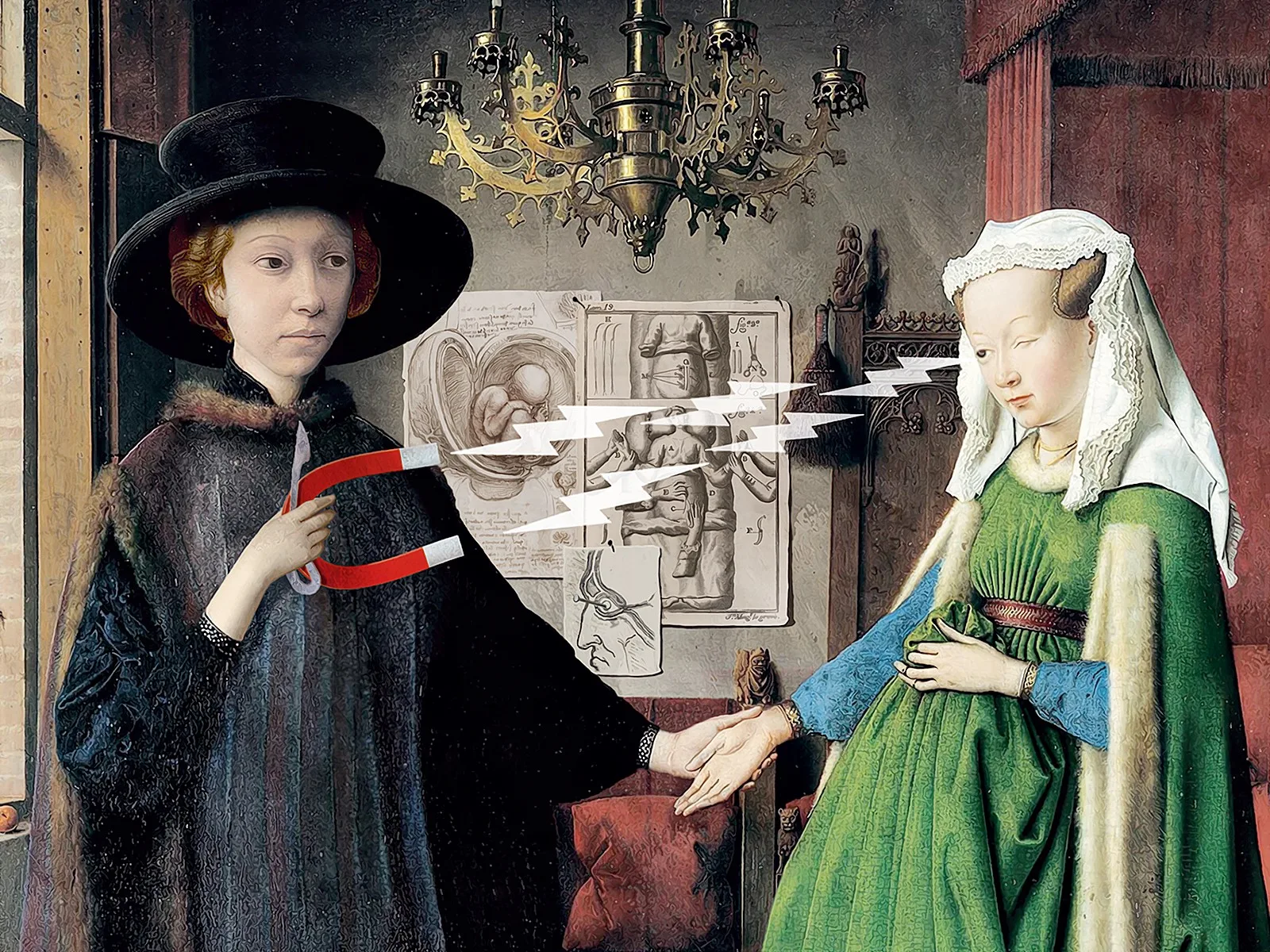

The Social Darwinist

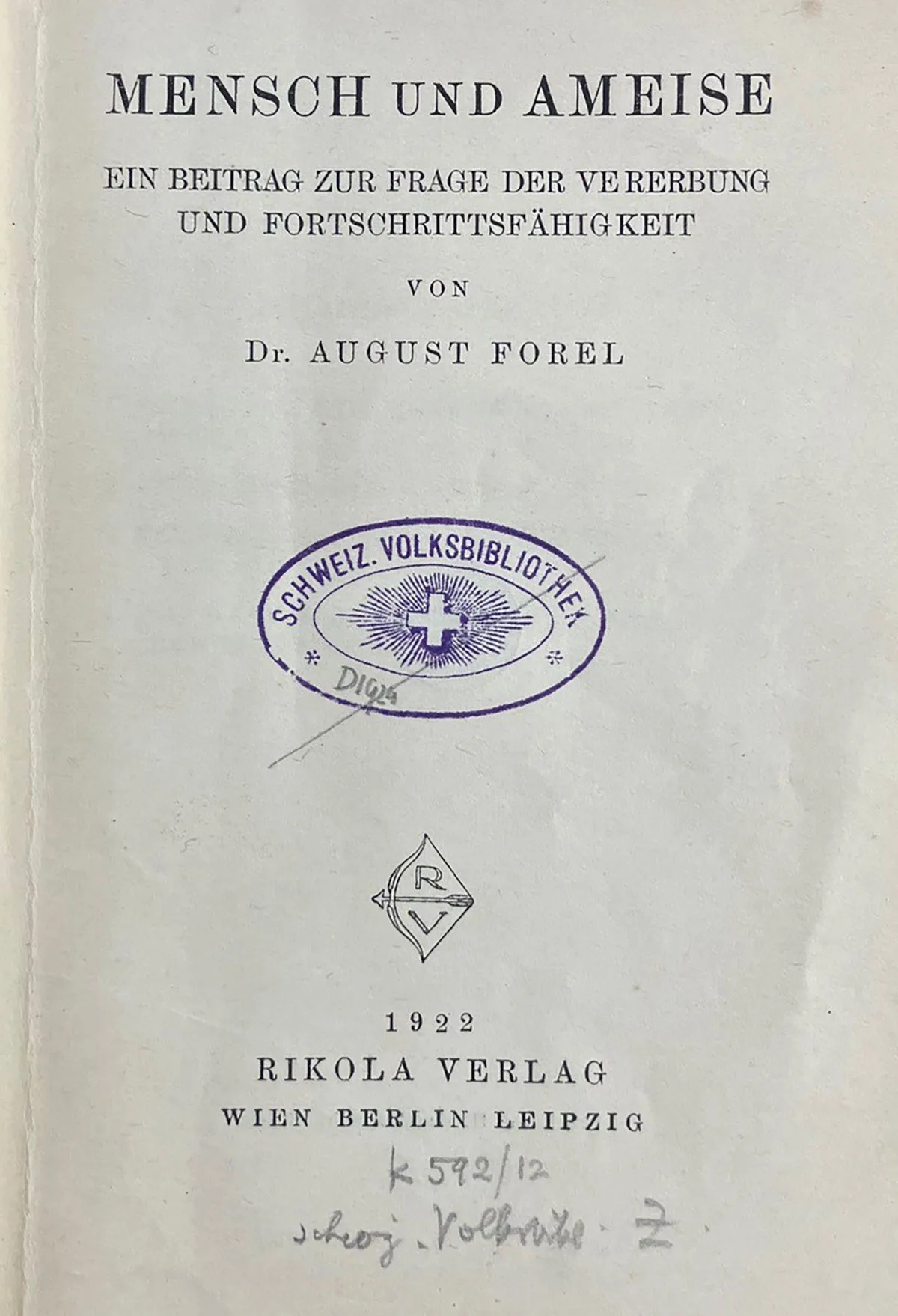

Race hygiene, eugenics, euthanasia

Sinister side – long ignored and hushed up

“From memorial to historical bind”