Letters from Amazonia

The 19th century can rightly be described as a ‘century of emigration’ in Switzerland. More than 400,000 people left the country to build new lives elsewhere. Letters from the period offer a glimpse into their day-to-day existence as expatriates.

The United States of America, map produced in 1877. The state of Missouri is highlighted in red.

Library of Congress

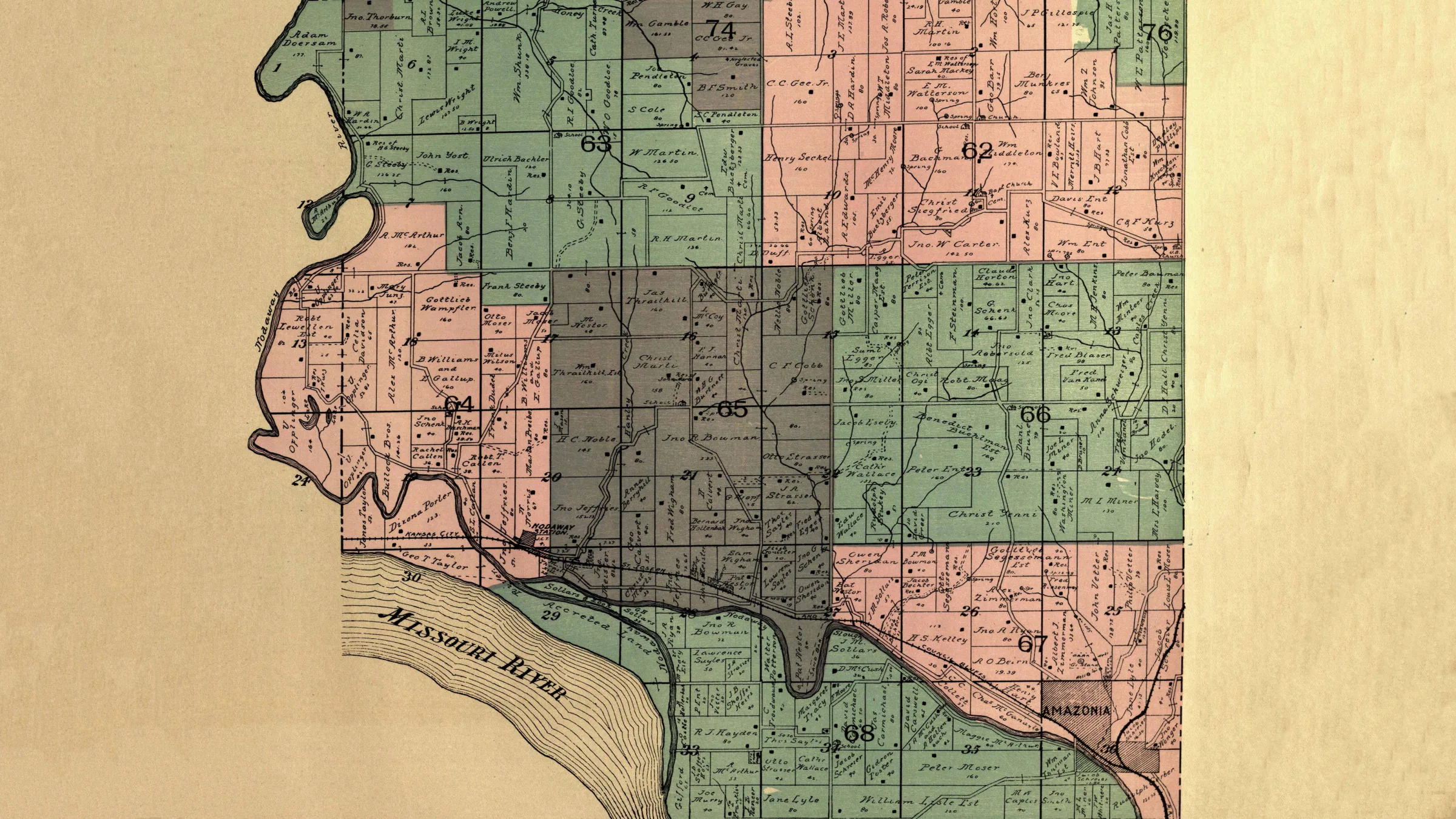

Andrew County and Amazonia lie in the north-western corner of Missouri. Map, 1897.

The State Historical Society of Missouri

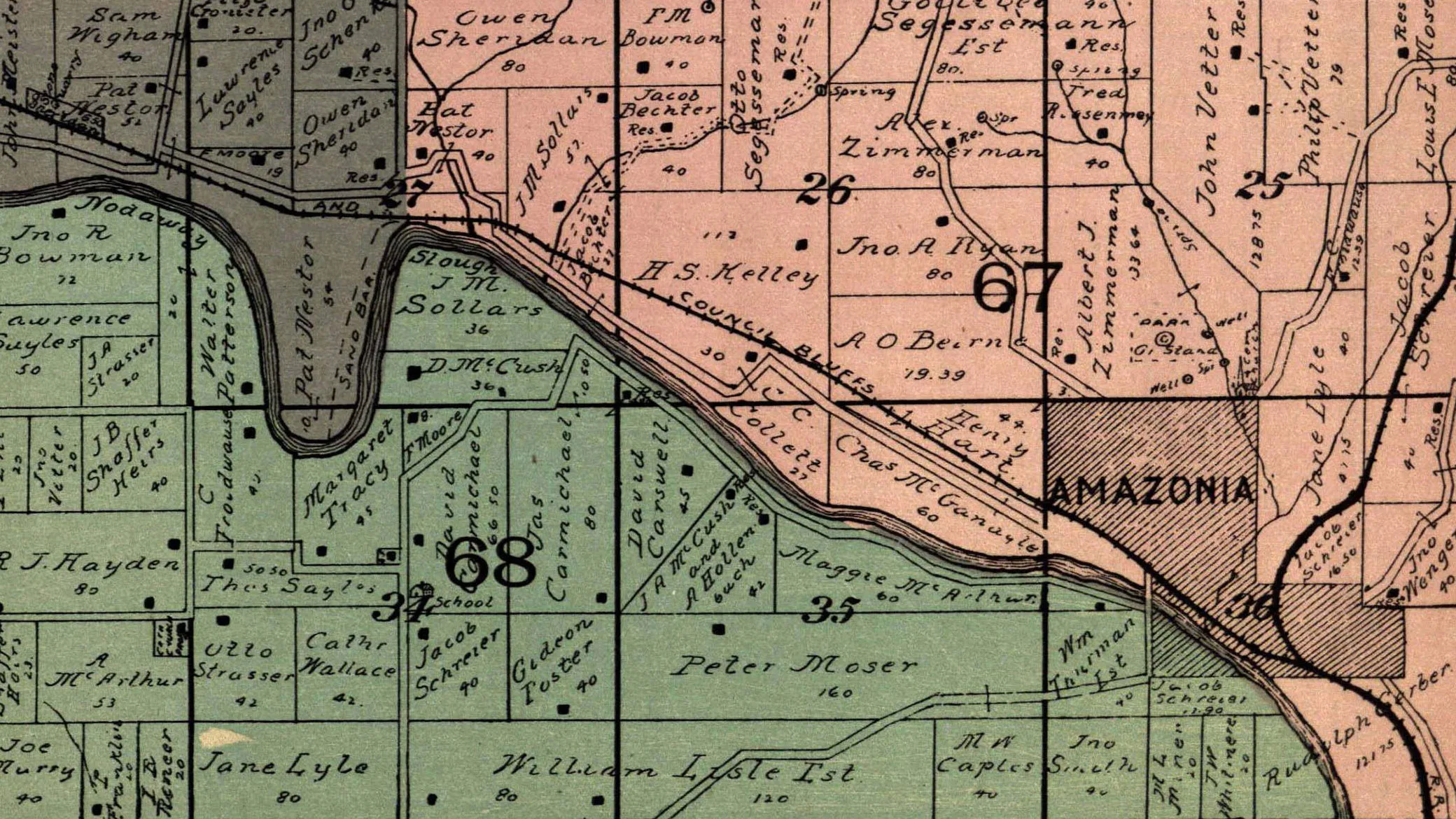

Peter Moser’s land is in the area numbered 35.

The State Historical Society of Missouri

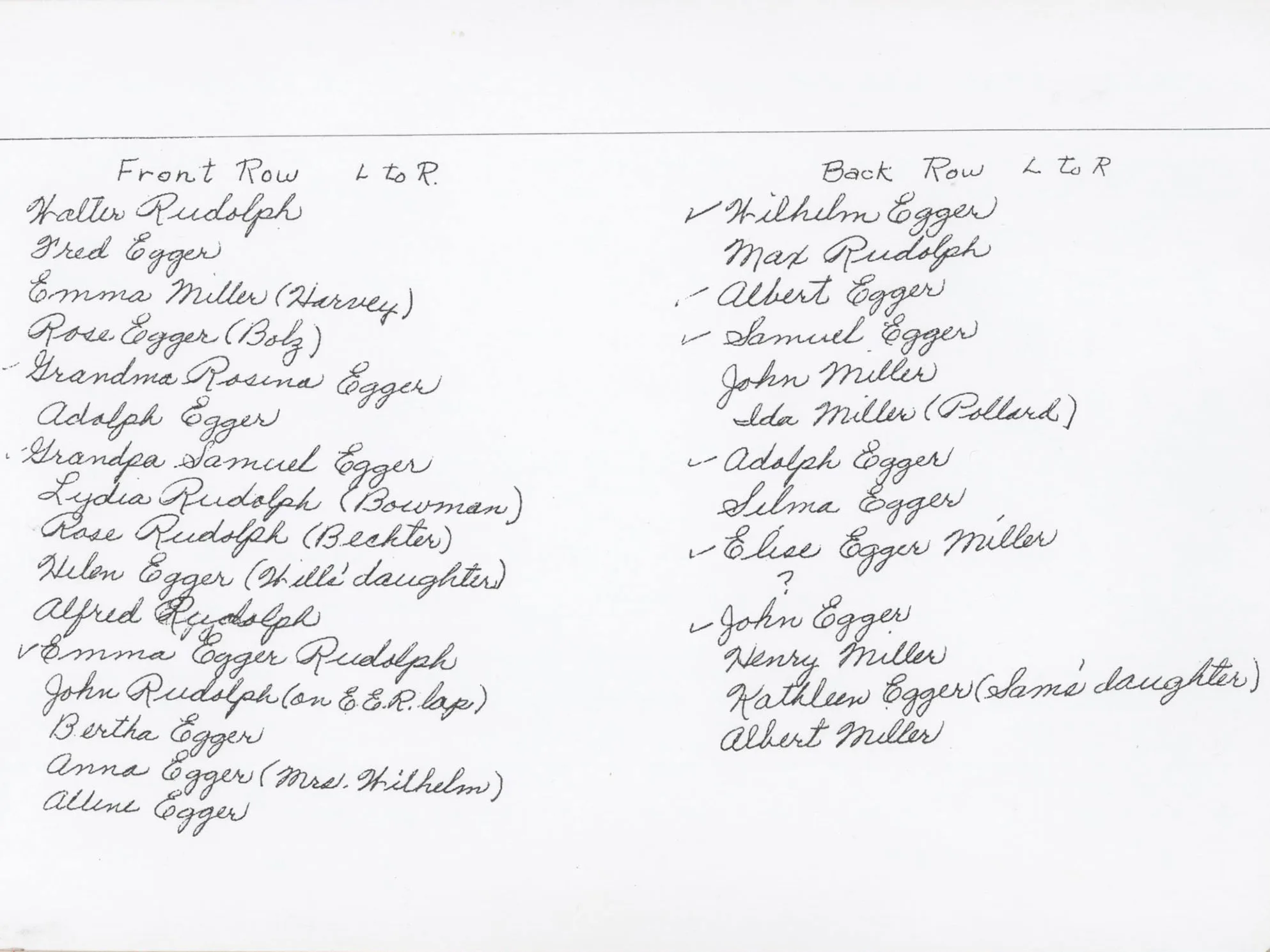

Samuel and Rosina Egger with their children and grandchildren. They had nine children; their oldest daughter stayed behind in Switzerland and another died shortly after birth. Andrew County Museum