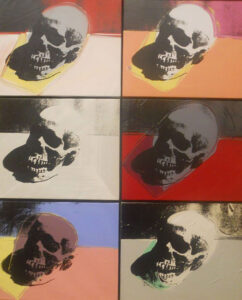

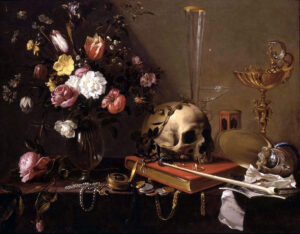

Skulls and Skeletons

Skeletons and skulls have become cult symbols through artists and rock bands. However, the representation of life and death have a much older tradition.

The collection

The exhibition showcases more than 7,000 exhibits from the Museum’s own collection, highlighting Swiss artistry and craftsmanship over a period of about 1,000 years. The exhibition spaces themselves are important witnesses to contemporary history, and tie in with the objects displayed to create a historically dense atmosphere that allows visitors to immerse themselves deeply in the past.