The ‘emigration’ savings model

In the 19th century some Swiss villages provided sponsorship to enable poorer members of their community to emigrate, to stave off financial ruin for the village. An example from the Canton of Aargau shows that this emigration wasn’t always entirely voluntary.

In 1855 the village of Niederwil (now Rothrist) paid for 305 people to emigrate to America. That was more than 12% of the local population. The Aargau village funded all travel expenses. This saved the community money in the long run, because paying for train and ship tickets was cheaper than supporting the poor for years to come.

In the mid-19th century, many people in the Confederation barely had enough to eat. The population grew rapidly and farming practices changed; the modernisation of agriculture affected peasant farmers in particular. The land was farmed more and more intensively, and the Allmenden or common land, the meadows and pastureland that was available free of charge for all members of the community, disappeared. While industrialisation had given peasant farmers the chance to earn money from home-based cottage industries, these earnings were usually not enough, because now the peasants had to buy expensive feed for their own animals as well. The situation was precarious, and Niederwil was no exception.

Not always voluntary

Following several poor harvests and a subsequent steep rise in prices, the textile industry entered a state of crisis. In 1855, the village was therefore faced with the choice of convincing a portion of its population to emigrate, or raising taxes yet again to continue financing pauper relief (Armenunterstützung) for the community’s poor. However, there was almost no hope of the latter, because by now even the more well-off were struggling to survive. So the village opted for mass emigration. The first tactic was to seek volunteers, but the authorities also pressured many villagers to leave. Some of these people were talked into emigrating, or lured with the prospect of a better life. If that wasn’t enough, the village authorities threatened to bring in the police. Most of the emigrants were receiving pauper relief, or were not far off doing so.

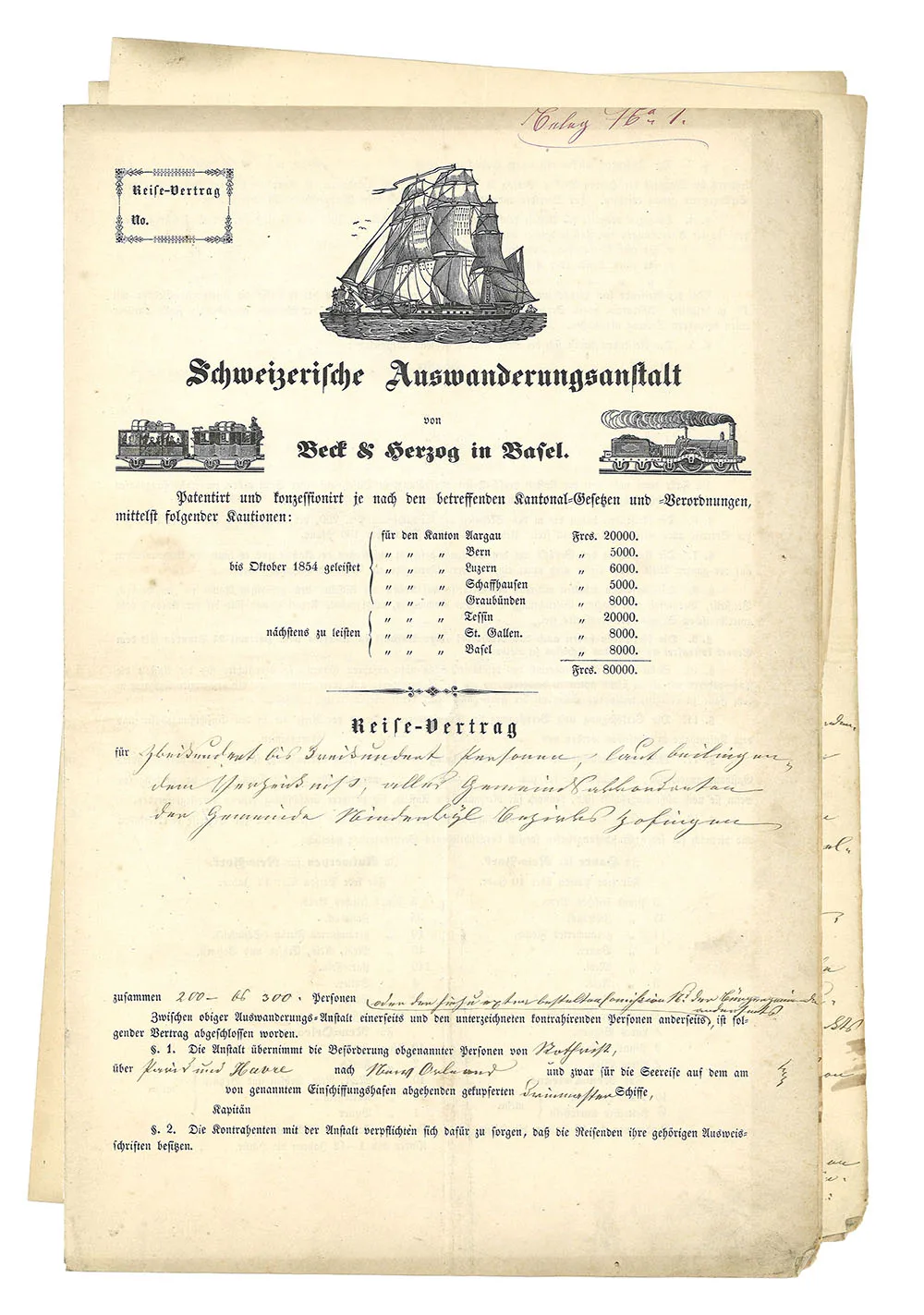

Via Basel to New Orleans

On 27 February 1855, the 305 emigrants set out for their new home. The journey took seven weeks, and the group travelled via Basel, Paris and Le Havre to New Orleans. From there, the Niederwil villagers were to travel on to St. Louis, where there were already several settlements of Swiss émigrés. They arrived there in May 1855. Some travelled on further, to places like New York, but most stayed in the St. Louis area.

The total cost of this mass emigration was around 50,000 francs. To fund it, the village had to borrow from banks and from wealthy members of the community. This emigration drive paid off financially for Niederwil. The community was able to close down its alms house just a year later. The fact that many of the emigrants were pressured into ‘their fortune’ has been suppressed for a long time.