How the linen trade brought wealth to Europe

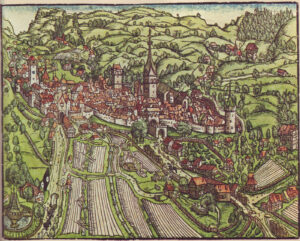

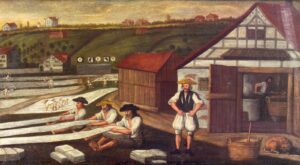

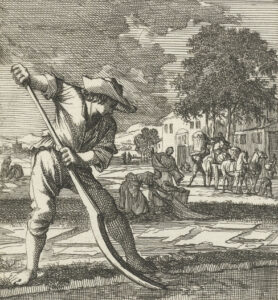

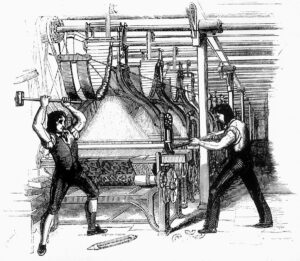

Linen production and trading was once the livelihood of many people in Europe, especially in eastern Switzerland. A famous landscape painting from the Netherlands in Kunsthaus Zürich tells a tale of global trade routes and mutual dependence.