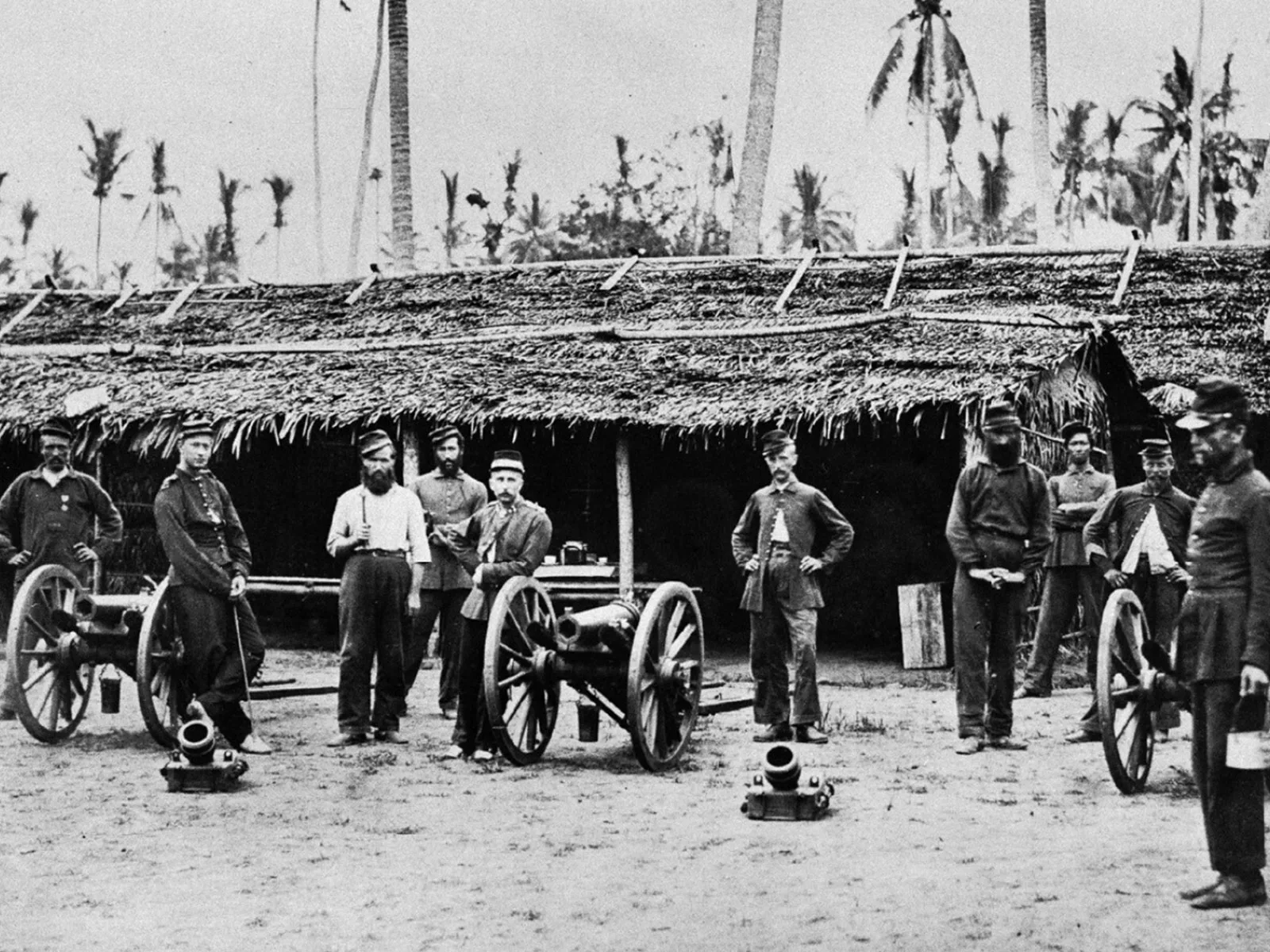

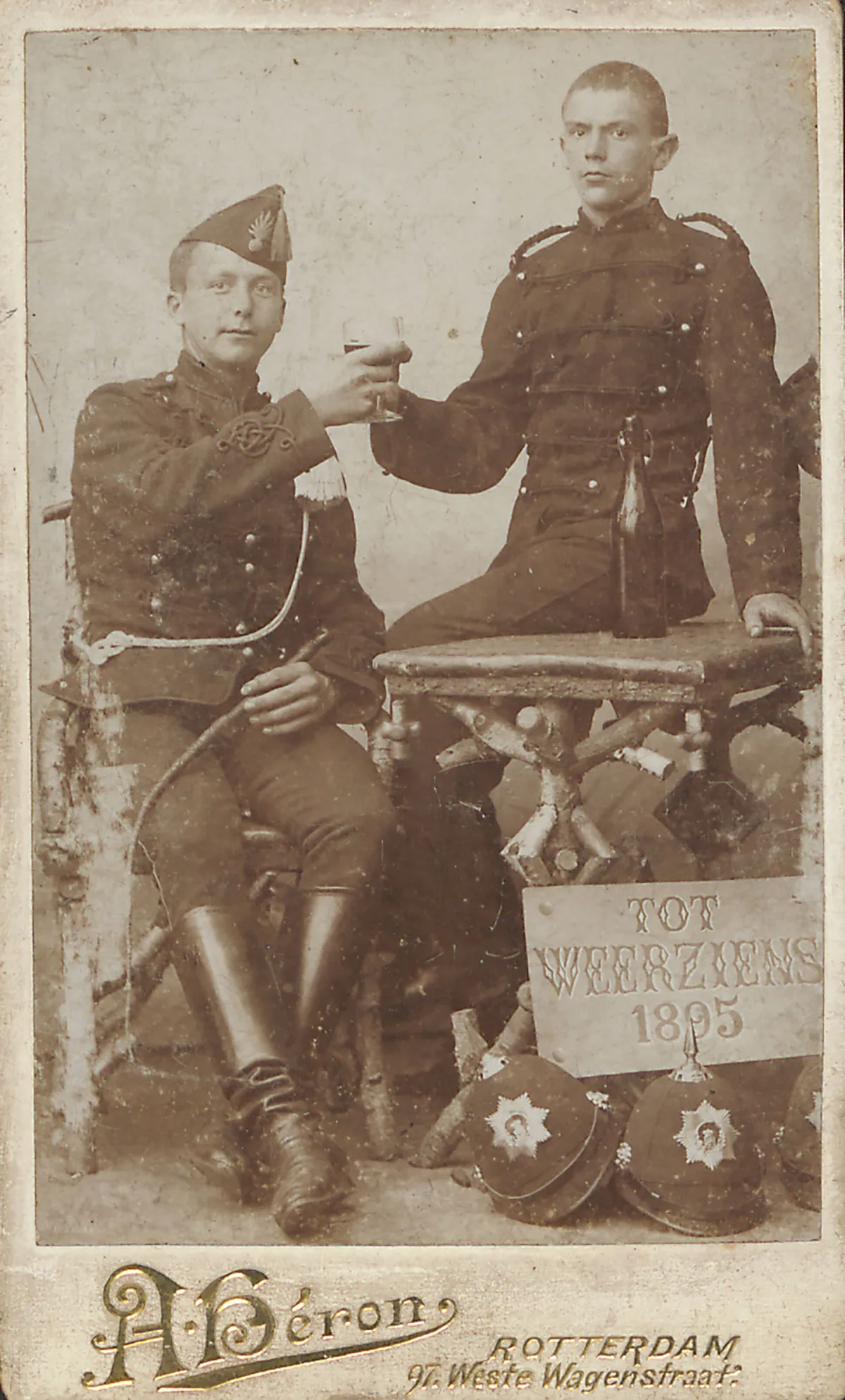

Swiss mercenaries in the Dutch colonial army

Between 1815 and 1914 around 7,600 Swiss mercenaries served in the Dutch colonial army. In search of work and adventure, they aided the violent expansion of the Dutch colonial empire in what is now Indonesia.

TV report on the Dutch East India Company. YouTube

Disenchantment with life in the barracks

Colonial violence