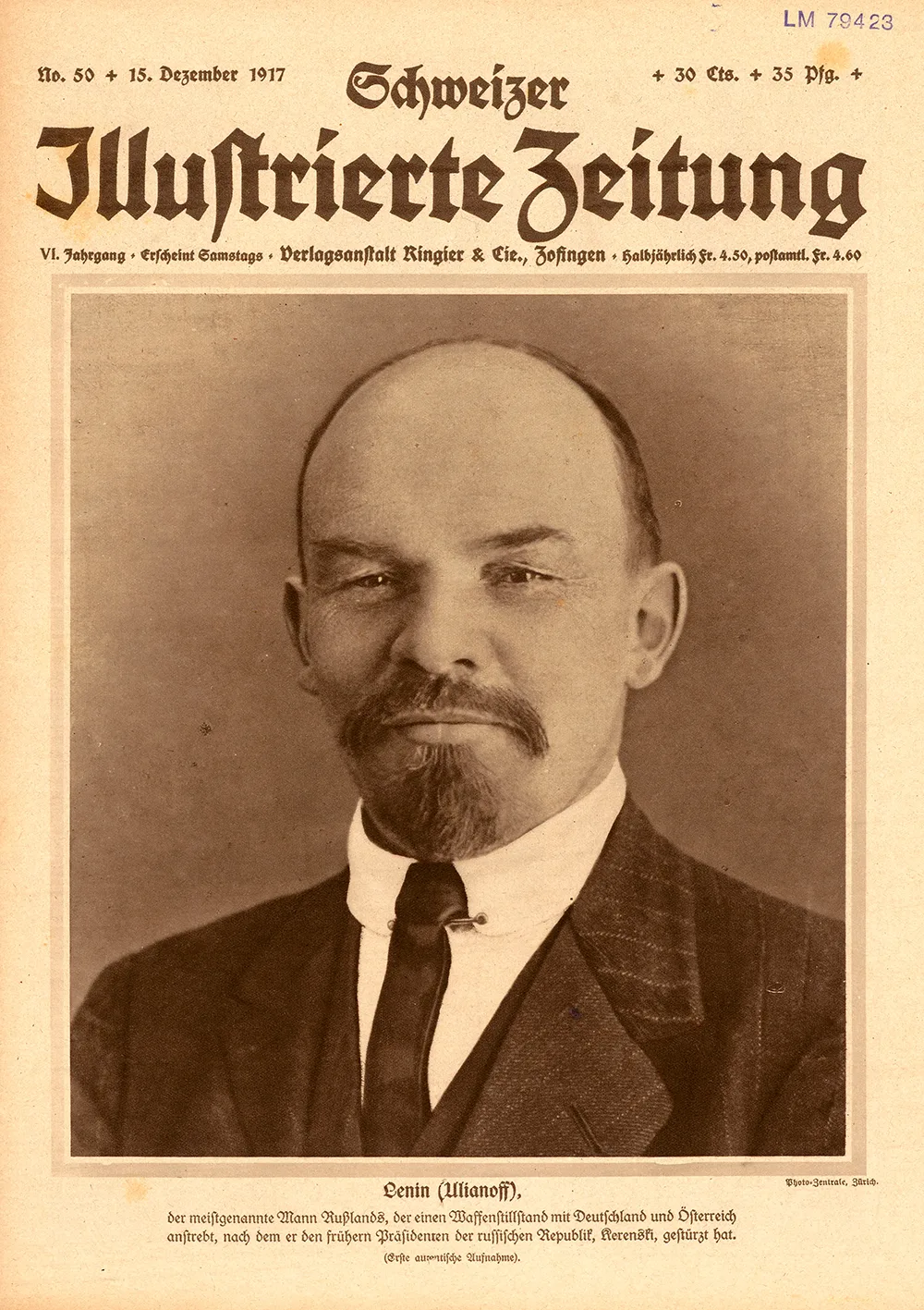

From Zurich’s backstreets to the centre of world revolution

Lenin’s explosive ideology, which would go on to shake the world, was partly concocted in Bern and Zurich. Yet he considered his Swiss comrades social romantics and opportunists.

Radicalisation in exile

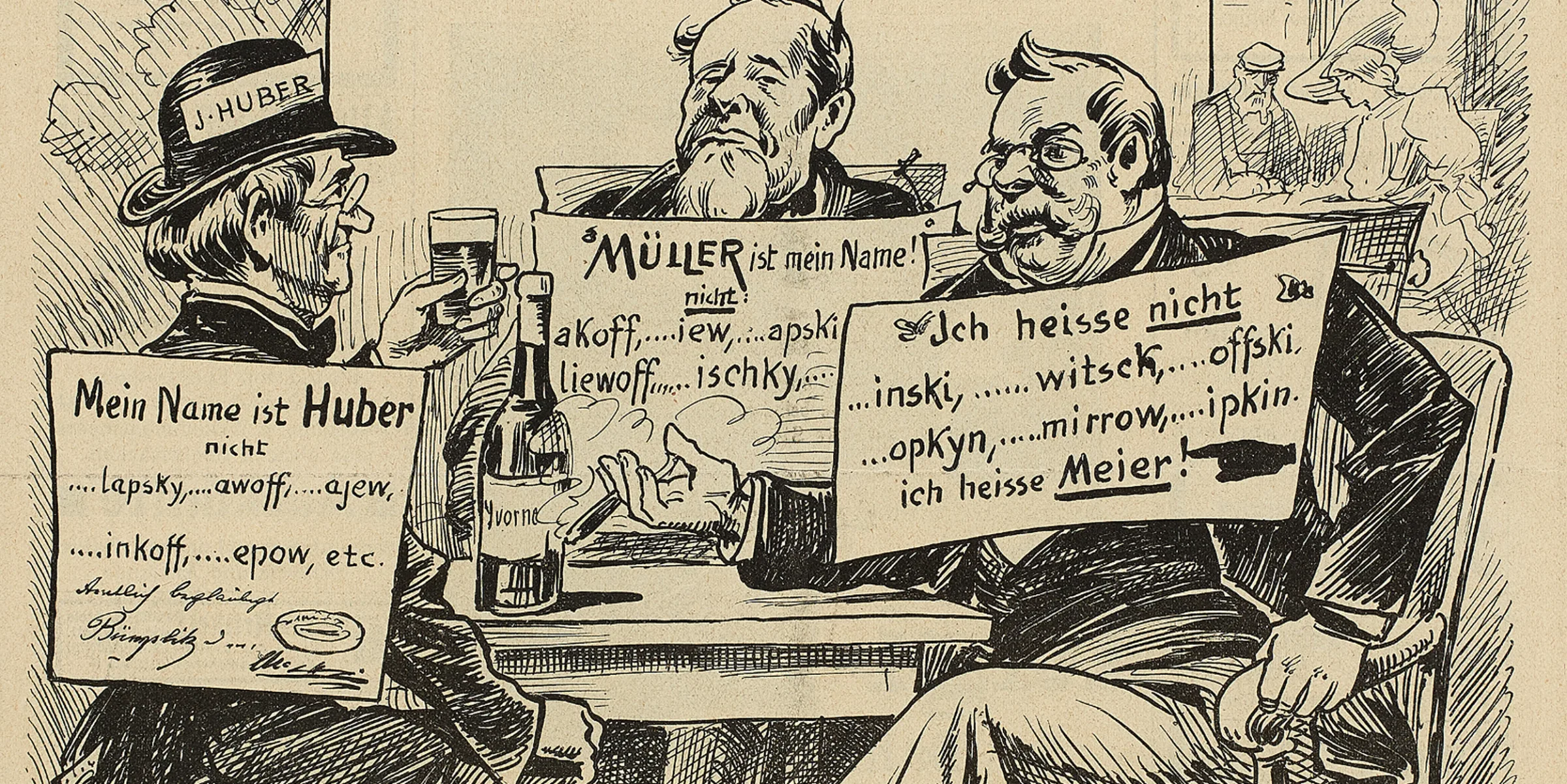

“Soaked in petty-bourgeois dullness”

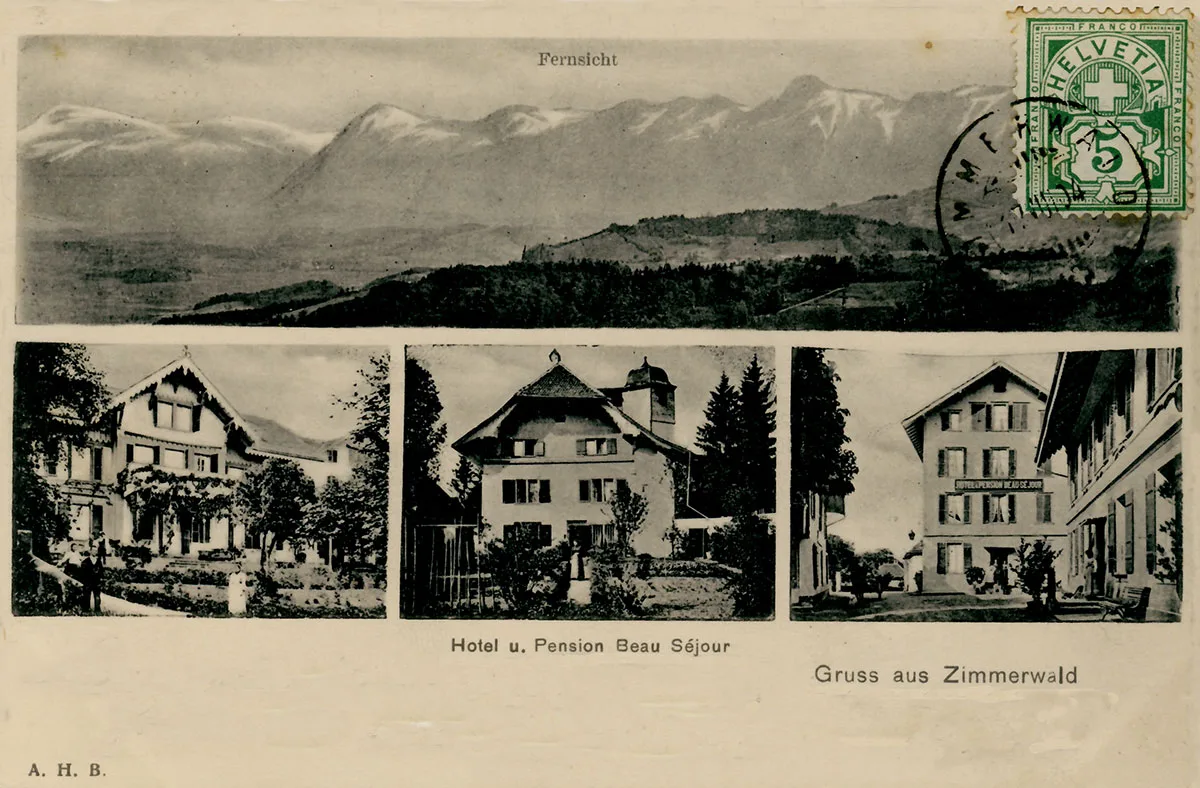

Under the guise of an ornithology society in Zimmerwald

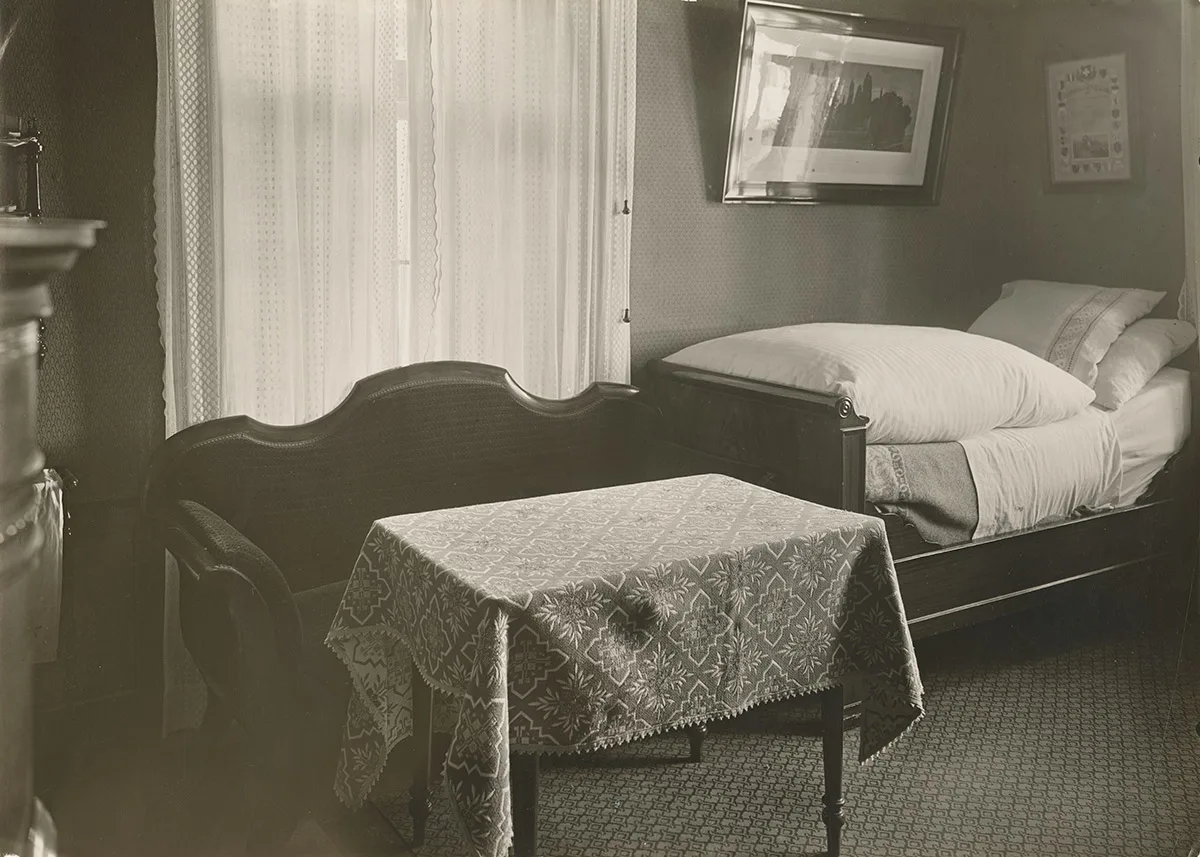

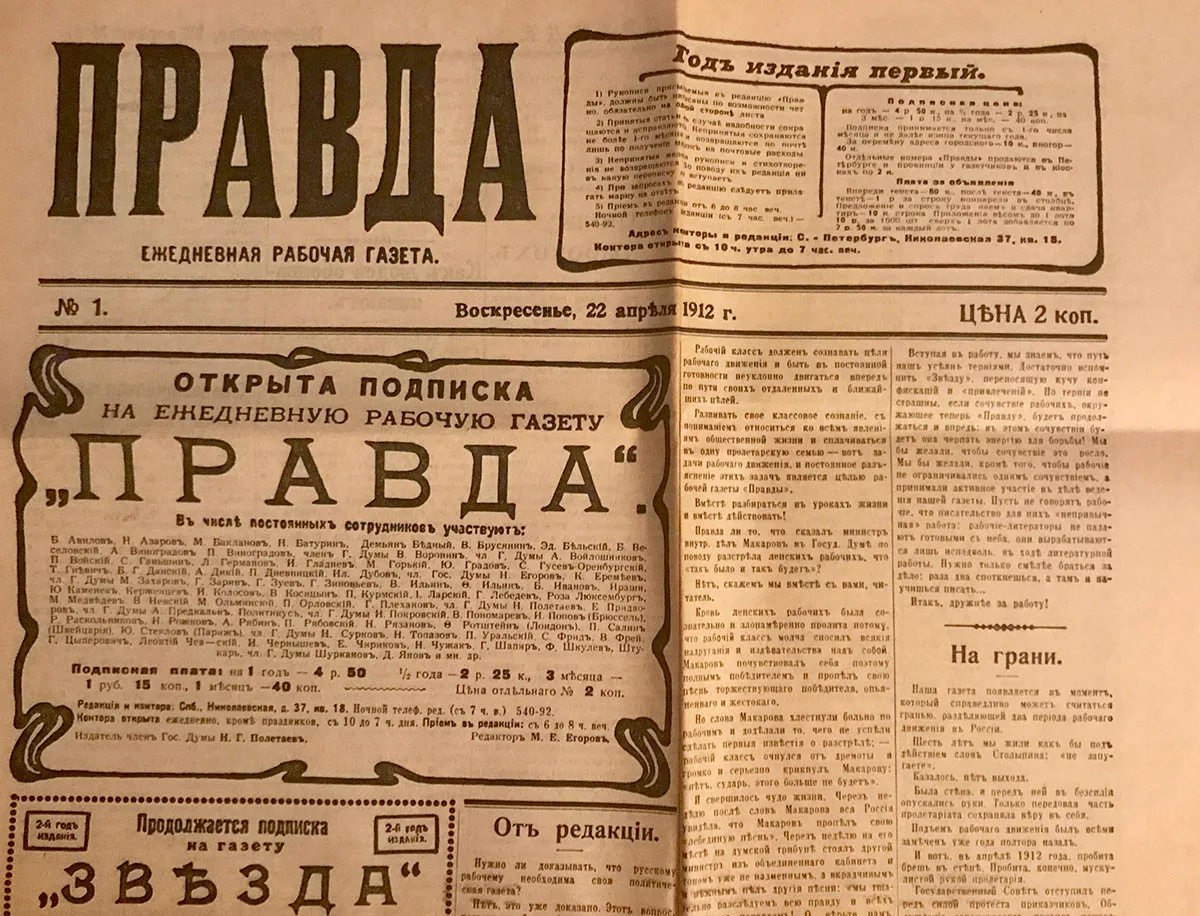

An explosive theory made in Zurich

TV report on Lenin’s return to Russia 1917. YouTube